IDP Korea Online

IDP launched in Korea in December 2010, and this double issue of IDP News celebrates this and the long links between Korea and the Silk Road, with articles from Korean scholars and the keynote address by Professor Mair. The support of the Research Institute for Korean Studies not only enabled the launch, but also the completion of digitisation of the sequence of fragmentary manuscripts from the Library Cave at Dunhuang held at the British Library and conserved with the help of Chinese colleagues in the 1980s.

In this issue we also report on the links being developed with institutions in Afghanistan to make known resources held in the British Library, along with an update of IDP news from our worldwide partners. The next issue will showcase the recently completed conservation and scientific work on the printed copy of the Diamond Sutra found at Dunhuang.

Launch of IDP Seoul

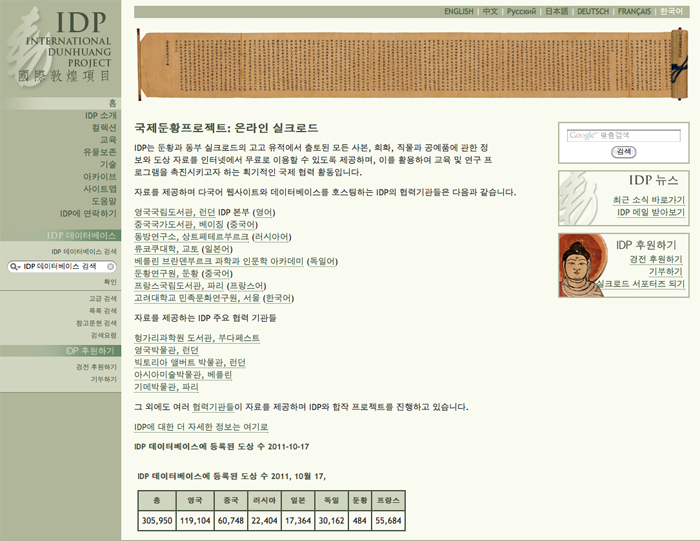

The IDP Korean website and centre in Seoul were officially launched by the Research Institute of Korean Studies (RIKS), Korea University on 2nd December 2010, thanks to the hard work of colleagues at IDP Seoul and London. The IDP Korean website is now online, bringing the Central Asian collections to new groups of scholars and the general public in Korea.

Speakers and guests visited the Central Asian galleries and the Silk Road exhibition at the National Museum of Korea before the official launch ceremony. The ceremony began with opening addresses from the former Director of RIKS, Heung-kyu Kim, and Director of IDP, Susan Whitfield. Korea University President Ki-Su Lee offered his congratulations, and the Chief Executive of the British Library Dame Lynne Brindley OBE expressed her appreciation of the work in a video message from London. Following a presentation on the history and work of RIKS, a demonstration of the IDP Korean website was given.

A symposium on the topic of Dunhuang, the Silk Road and Korea followed and featured three keynote addresses given by Dunhuang scholars Victor H. Mair (University of Pennsylvania), Wenhsin Yeh (University of California Berkeley), and Kyung-wook Jeon (Korea University). Victor Mair spoke of the impact of IDP on Dunhuang studies drawing on his own experience and stressing the importance of digitisation in making the manuscripts and artefacts available to scholars worldwide. In her paper on Dunhuang manuscripts and the internationalisation of Chinese studies in China, Wenhsin Yeh argued that scholarship on Dunhuang from outside China challenged Chinese scholars and stimulated the field within China. Kyung-wook Jeon discussed the primacy of Korea’s role in Dunhuang and the Silk Road in his paper citing music, entertainment, and other evidence of Korea’s influence and cultural exchange with Central Asia.

After the successful launch of IDP Korea, Professor Heung-kyu Kim expressed his hope and determination that it would stimulate research on Dunhuang, the Silk Road, and Central Asia in Korea and worldwide. Although the interest and involvement in Dunhuang Studies on the part of RIKS may seem unexpected and surprising, Professor Kim said that it conformed to the expansion that began in the late 1990s of RIKS Korea-related research in a more international context.

In addition to providing access to data and images of collections from Dunhuang and the Eastern Silk Road to Korean researchers and the general public, IDP Korea will focus its interests on Central Asian culture and history, including Dunhuang and the Silk Road as the historical background for establishing cultural links through clan migration, pilgrimage and commercial transactions. Korea’s geopolitical position is such that research on cultural links transmitted by both land and sea routes is important. While these links provide an understanding of the past, they may also have relevance for the future. It is hoped that the development of the IDP Korea centre will encourage research projects in this area.

Yoon-Hee Hong

Research Professor and Head of IDP Korea

Korea and the Silk Road

Recent research by scholars is revealing the rich links that exist between the historical kingdoms of the Korean peninsula and, through the routes across the steppe, the peoples and cultures of Central and West Asia. Korea’s links with South and East Asia, notably through the legacy of Buddhism, are also well-attested. Despite its geographical position on the eastern extremity of Eurasia, the peoples of Korea therefore played an important role in the development of Eurasian culture and in the story of the Silk Road.

As a scholarly resource for all those interested in learning more about the cultural exchanges along the Silk Road, IDP aims to encourage and support Korean scholarship in this area. IDP was therefore delighted to have the opportunity to work together with colleagues at the Research Institute for Korean Studies (RIKS), Korea University to establish a Korean version of the IDP website in 2010. We very much hope that the local website will enhance knowledge of and access to IDP’s resources for local scholars and students.

From its inception in 1993 at a meeting of curators and conservators working with Central Asian material from institutions worldwide, IDP has had a vision of providing easy access to high-quality data on the archaeological legacy of the Eastern Silk Road through multilingual websites. Following the initial online English-language site, which went live in 1998, IDP has worked together with its partner members worldwide to launch different language websites. These started with IDP China in 2002 hosted by the National Library of China, and now include sites in Russian, French, German and Japanese, with Swedish partners coming on board in 2011. The website will also shortly have pages in Turkish and Arabic.

Collaboration started with the RIKS in 2009 and a schedule was set to launch the website in autumn 2010. Preparing multilingual websites and, just as importantly, multilingual metadata to allow searches in all these languages, involves considerable work, both translation and technical. The International and Technical Manager at IDP UK, Vic Swift, worked very closely with the team at Korea University over the course of 2010 to prepare for the launch. This not only involved the translation of the web pages, but also adding Korean to the metadata concordances within the database, so allowing scholars to search the database in Korean. She also assisted on the set-up of a server at RIKS to host the database and website.

IDP Seoul was successfully launched in December 2010. The launch would not have been possible without the hard work and skills of the staff at RIKS who were unfailingly helpful and efficient. This bodes well for the future of IDP Seoul — IDP encourages all its partner institutions to take an active role in customizing areas of its website, arranging local programmes of events and in suggesting joint initiatives with other IDP partners, including academic conferences, research and educational projects, exhibitions, and publications.

We very much look forward to working together closely to bring the resources of IDP to Korean scholars, schoolchildren and the public, and to enhance awareness worldwide of Korea’s role in Silk Road history and culture.

Susan Whitfield

The Impact of IDP on Dunhuang Studies

Victor H. Mair

Since I began my career in Dunhuang Studies as a graduate student at Harvard University in 1972, the field has witnessed tremendous changes. During the 1970s and early 1980s, while writing my dissertation and doing research for my first publications,1 I travelled to London, Paris, Leningrad (now, again, St. Petersburg), Dunhuang, Beijing, Kyoto, and elsewhere to examine firsthand several hundred Dunhuang manuscripts. However, due to various practical considerations and constraints, I was unable to stay in any of these places as long as I would have liked, and consequently I did not get to see directly with my own eyes as many manuscripts as I wished.

To make up for this lack, I spent a couple of summers working at Cornell University, whose library was the first in the United States, and one of the first in the world, to purchase the microfilms of all the Dunhuang manuscripts in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the British Library, and the Beijing Library (now the National Library of China). During the months I spent at Cornell, I very quickly looked through all 40,000 or so microfilmed manuscripts in the collection. It was because of my experience at Cornell that I was able to write the long article entitled ‘Lay Students and the Making of Written Vernacular Narrative: An Inventory of Tun-huang Manuscripts’,2 which I consider to be one of my most important publications in Dunhuang Studies. Unfortunately, because it appeared in an obscure journal, few people have ever seen it. Consequently, I am considering the possibility of having it reprinted in a more accessible venue, perhaps online in Sino-Platonic Papers.3

While the microfilms of the Dunhuang manuscripts at Cornell University were a tremendous boon to my research, they had several drawbacks. First and foremost, of course, I could not consult them easily and regularly, but had to travel a long distance and find housing whenever I went to Ithaca, New York. The method of reading the manuscripts in this form was not that convenient either, since I had to peer into a back-lit dark space that caused a strain on my eyes after several hours. Furthermore, I had to spin the microfilms back and forth when I searched through them, so it was not easy to find a particular manuscript, much less a particular spot on a given manuscript on the tapes that were approximately 100 feet long. While the microfilms had their disadvantages, I was enormously grateful for them, until something else more convenient came along.

The Dunhuang Baozang 敦煌寶藏 (1981–86) came next, edited by Huang Yongwu, in 140 large volumes, and what a boon it was!4 Affordable for most good research libraries at universities with a graduate program in Chinese Studies, Dunhuang Baozang was essentially a transfer to book format of the images on the microfilms, one set of which I had used so assiduously at Cornell. Not only was the Dunhuang Baozang affordable, it was also remarkably handy. Within a couple of library bookcases, one had at one’s fingertips the overwhelming bulk of Dunhuang manuscripts. What is more, using the index volume, it was fairly easy to locate a particular manuscript among the many thousands in the collection. A significant drawback, however, was that the clarity of the images left much to be desired. The resolution and printing were often simply not sharp enough for one to determine with certainty the strokes of the characters in texts that one was trying to read.

Around the same time as the Dunhuang Baozang appeared Lev Nikolaevich Menshikov, L. I. Chuguevkii, and their Russian colleagues began to publish Dunhuang documents in the holdings in the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (Saint Petersburg). Dunhuang manuscripts scattered around the world, in Japan, Denmark, Finland, even Philadelphia, were also being published in bits and pieces. But it was almost impossible to keep track of them because they often appeared in private editions or in more or less obscure journals.

Finally, major Chinese publishing houses, such as the Sichuan People’s Publishers and Shanghai Classics Press, began to make contracts with the main libraries and archives holding Dunhuang manuscripts and then started to publish them in large volumes of high-quality photographic reproductions. These were far superior to the images provided in Dunhuang Baozang and, as such, they could be used for critical research on the manuscripts. The level of detail in these large volumes was remarkable, and enabled scholars to read the manuscripts almost as well as if they were holding them in their hands. There were, however, a number of significant drawbacks, first among them being the very high price of the sets, which put them beyond the reach of all but the very wealthiest individual scholars, and even beyond the reach of all but the best funded research libraries. These sets coming out from Chinese publishing houses, moreover, were cumbersome and bulky, making them far more difficult to house and handle than the volumes of the Dunhuang Baozang. Finally, there were often complications and delays in the production, publication, and distribution brought about by misunderstandings between the host libraries holding the manuscripts and the Chinese publishing houses, but also by the sheer scale and scope of the projects.

That, essentially, is where things stood when the International Dunhuang Project (IDP) was formed in 1993, under the leadership of staff members at the British Library. It is neither my purpose nor my place to recount the early history of IDP, for there are others far better qualified to do so than I. My intention here, rather, is to give a brief indication of how IDP has had an impact upon individual scholars who work on Dunhuang manuscripts and upon the field of Dunhuang Studies in general.

The advantages of having high-quality digital images of the Dunhuang manuscripts freely available to interested scholars online are so numerous as to be almost uncountable. First of all, we no longer have to leave our carbon footprints all over the atmosphere in going to wherever the manuscripts we need to see happen to be. Rather, the images fly instantaneously into our own studies. Not only does that help to save our planet, it also personally saves us lots of money (think of the travel, housing, and food costs incurred in travelling long distances around the globe to visit the various libraries where Dunhuang manuscripts are stored) and endless amounts of time. Secondly, having scholars work from high quality digital images of the manuscripts rather than with the manuscripts themselves contributes immeasurably to the conservation of the manuscripts. In addition, to make the manuscripts accessible to individual scholars usually entails outfitting them with some sort of protective and reinforcing material, which usually results in reduced visibility of the surface of the manuscript. Thus, a high quality photograph or digital image of a manuscript is often clearer than the protected manuscript itself.

Something else I have realized in working with archeologically recovered objects is that high-quality photography very often reveals details not evident to the naked eye. This seems paradoxical, but somehow a skilled photographer manages to bring out colours, shades, marks, and other properties of an artifact that are not visible to the unaided eye. The same is true of manuscripts. I still remember working at the old British Library. I would hold a manuscript up to the light and turn it around in different directions and view it from various angles so that I could see faint traces of writing. In the end, I did manage to discover some very important inscriptions and notations that had never been noticed, much less published, before. However, it all would have been so much easier if IDP had been in existence when I was doing my research back in the 1970s and 1980s of the last century! Now, in the comfort of one’s study, one may view the image of a given manuscript in whatever orientation one pleases, enlarging it, and enhancing the image by a variety of means that would have been impossible if one were working directly on the physical manuscript itself. Sometimes (I would say frequently), a virtual manuscript or artifact is preferable to a real manuscript or artifact.

I could go on and on outlining the advantages that are now available to us through IDP, such as all of the catalogues that have been posted to the site and the countless links to useful resources. The next generation will be able to make many breakthroughs that were beyond us, in no small part because we did not have fast and efficient tools such as those provided by IDP. Nonetheless, far from feeling envious of those of you who will benefit most from IDP, I wish only to encourage you to make the best use of it.

Before closing, I would like to point out that, in order to realize the full potential of IDP, we must all cooperate in doing whatever is necessary to complete the digitization of the entire corpus of Dunhuang manuscripts. That seems almost like an infinite, and extraordinarily expensive, task. Still, when we look at what a relatively small number of dedicated individuals have accomplished with severely limited resources, we can be confident that if more committed persons and an expanded circle of patrons and donors joins them, the completion of the IDP dream can, and will, be realized within our lifetimes.

Victor H. Mair is Professor of Chinese Language and Literature at the University of Pennsylvania. This paper was given as a keynote at the official opening ceremony of IDP Korea in Seoul on 2nd December 2010.

NOTES

1. Victor H. Mair, Tun-Huang Popular Narratives (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983); Painting and Performance: Chinese Picture Recitation and Its Indian Genesis (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988); T’ang Transformation Texts: A Study of the Buddhist Contribution to the Rise of Vernacular Fiction and Drama in China (Cambridge, Mass.: Council on East Asian Studies Harvard University: Distributed by Harvard University Press, 1989).

2. Victor H. Mair, ‘Lay Students and the Making of Written Vernacular Narrative: An Inventory of Tun-huang Manuscripts’, Chinoperl Papers 10 (1981): 5–96.

3. Sino-Platonic Papers Website

4. Huang Yongwu 黃永武 (ed.), Dunhuang Baozang 敦煌寶藏 (Dunhuang manuscripts) (Taibei shi: Xin wen feng chuban gongsi, 1981–86).

The Significance of Dunhuang Studies in Korea

Kwon Young-pil

The Growth of Dunhuang Studies

Dunhuang was established as a field of study in the early twentieth century after the contents of the Dunhuang Library Cave became known and the Mogao Cave complex was studied and conserved. Around 40,000 manuscripts were removed to institutions worldwide by foreign archaeologists and explorers. Another 10,000 manuscripts were taken by the Chinese government to Beijing in 1911. Dunhuang studies collectively represent the history of wall paintings and Buddhist statues in Dunhuang as well as a wide range of academic disciplines involving analysis of the Dunhuang manuscripts, including history, archaeology, religion, geography, linguistics, bibliography, literature, folklore, and science.1

Over the past century, major achievements and breakthroughs have been made in this field. The International Dunhuang Project (IDP) was established in 1993 by institutions holding Dunhuang material worldwide at a meeting organised by the British Library, where the Stein collection of Dunhuang manuscripts is held. IDP’s aim is to promote international cooperation in the study and conservation of Dunhuang and Eastern Silk Road manuscripts and artefacts scattered across the globe, an important part of which is making digital surrogates available online. This further expedited the study of Dunhuang. In Korea, the Korean Society of Dunhuang Studies was founded in 1987 exclusively to study Dunhuang. The Korean Association for Central Asian Studies was later formed in 1996 to facilitate the study of Dunhuang within the purview of regional studies.2 Dunhuang studies in Korea took a major step forward in 2010 when the Research Institute of Korean Studies (RIKS) at Korea University and IDP forged a partnership.

Korea and Dunhuang

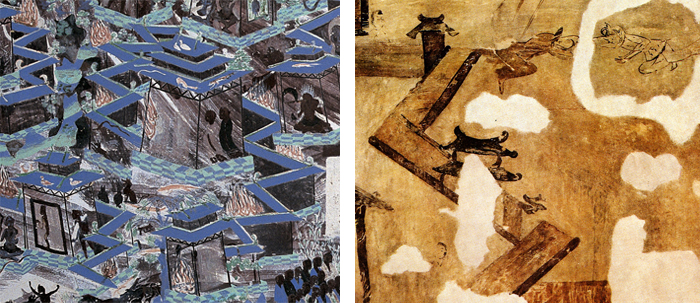

Although Korea is a relative latecomer to this field of study, the international academic community has acknowledged that direct links between Korea, Dunhuang and Central Asia are evident from both the Dunhuang wall paintings as well as the manuscripts. A total of 492 Dunhuang caves has been identified and studied, and Korean envoys wearing feather caps (characteristic of Korean officials in ancient times) are depicted in murals of the Tang period (618–907) including those in caves 220, 237, 332, and 335 (see above). These are certainly of great interest3 as they are evidence that Koreans travelled westward passing through Dunhuang.

When comparing Dunhuang cave paintings and Goguryeo tomb murals, a mutual influence is clearly discernible. The representation in the form of a ‘folding fan’ in Tomb Mural4 in Jinpari, Goguryeo (first half of the sixth century) shows the unmistakable influence from a cave painting in Dunhuang Mogao Cave 288. Furthermore, the representation of the cornice dentils shown in a tomb mural in Palmyra (first century), an important Silk Road hub, are also seen at Bamiyan (cave 620, fifth century), at Kizil (cave 47, fifth century), at Mogao at Dunhuang (cave 272, first half of the fifth century), and at the Complex of Goguryeo Tombs (Susan-ri Tomb, second half of the fifth century).5 American art historian Michael Sullivan argues that the zigzag shape on the mural painting in Samsilchong, Goguryeo (second half of the fifth century) influenced the mural in Dunhuang Mogao Cave 420 (see above).6

Bottom: The National Museum of Korea.

The fact that A Travel Account to the Five Indian Kingdoms by Hyecho was among the manuscripts found by Paul Pelliot in the Dunhuang Library Cave is also significant, not only from the perspective of Buddhist history but also relating to exchange between Korea and the West.7 This indicates the existence of a network of cosmopolitan cities connecting Gyeongju, Chang’an and Dunhuang. Furthermore, brothers Park Won-hong and Park Won-jang, deemed to be ancient Koreans, are described in a Dunhuang manuscript in the Pelliot collection (Pelliot chinois 5522, ninth century) that represents a cross-section of the social structure of Dunhuang.

The Dunhuang historical documents are of great value for the history of Buddhism. The Tripitaka Koreana, for example, can be compared against the Buddhist records in the Dunhuang documents, allowing an assessment of its accuracy as the standard version8 and for studying engraving practices.9

The National Museum of Korea holds a collection of paintings from the Dunhuang Mogao Caves, important for the study of art at Dunhuang. The study of Dunhuang today, however, includes aspects that extend beyond a historical record of the past. For instance, Korean artist Yong Suh has copied Dunhuang wall paintings, taking inspiration from the originals. He stayed in Dunhuang for seven years (1997–2004), producing more than fifty exact copies of Dunhuang wall paintings during his stay while also creating his own works. He has held solo exhibitions on Dunhuang paintings in Beijing and Seoul since 2004, and obtained a PhD in Dunhuang studies from Lanzhou University in 2007. His works allow us to experience a new dimension of Dunhuang art.

This outline of the significance of Dunhuang studies in Korea clearly shows that the study of cultural links between Korea, Dunhuang and the Silk Road is an important topic for researchers in Korea.

Kwon Young-pil is a member of the IDP Korea Advisory Committee to IDP Seoul, and a Visiting Professor at Sangji University.

NOTES

1. The concept of Dunhuang studies has recently been expanded to include ‘cultural relics excavated around the areas of Turfan and the Silk Road,’ see Rong Xinjiang 榮新江, Dunhuangxue xinlun 敦煌學新論 (New Theory on Dunhuang Studies) (Lanzhou: Gansu jiaoyu chubanshe, 2002), 145.

2. The Korean Association for Central Asian Studies organised a conference in 2007 entitled ‘Dunhuang Studies in Global Perspective: Conservation, Research and Collections’ where Li Zuixiong 李最雄 (Dunhuang Academy), Okada Ken 岡田健 (National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo), Kira Samosyuk (State Hermitage Museum), Jacques Giès (Musée Guimet), Susan Whitfield (IDP, British Library), Suh Yong 徐勇 (Dongdoek Women’s University, Korea), Kwon Young-pil 權寧弼 (Sangji University, Korea) gave papers (see picture opposite).

3. The fact that ancient Koreans appear in the Dunhuang wall paintings was first noted by Duan Wenjie 段文傑, the former director of the Dunhuang Academy. Duan Wenjie, Dunhuang shiku yishu lunji 敦煌石窟藝術論集 (Collection of Papers on Dunhuang Cave Art) (Lanzhou: Gansu renmin chubanshe, 1988), 294.

4. Young-pil Kwon, ‘Goguryeoui daeoemunhwagyoryu’ (Cultural Exchange of Goguryo with Other Countries), Goguryeoui munhwawa sasang (Culture and Philosophy in Goguryeo) (Northeast Asian History Foundation, 2007), 258-59.

5. Young-pil Kwon, ‘West Asia and Ancient Korean Culture: Revisiting the Silk Road from an Art History Perspective,’ International Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology 3 (2009): 162-63.

6. Michael Sullivan, The Birth of Landscape Painting in China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962), 151. Young-pil Kwon, ‘The Relationship between the Goguryeo Wall Paintings and Central Asian Art’ (in Korean), in History and Culture of Central Asia, ed. Young-pil Kwon et al. (Seoul: Sol, 2007), 14-15.

7. Important research on Hyecho published in Korea includes: Byeong-ik Go, ‘Wang ocheonchukguk jeon (A Travel Account to the Five Indian kingdoms) by Hyecho,’ in Study of International Exchange in East Asia, (Seoul National University Press, 1970). There is also Wang ocheonchukguk jeon (A Travel Account to the Five Indian Kingdoms) by Hyecho, with translation and commentary by Su-il Jeong (Seoul: Hakgojae, 2004), and Dong-shin Nam, ‘Wang ocheonchukguk jeon (A Travel Account to the Five Indian Kingdoms) by Hyecho’, Silk Road and Dunhuang: Journey to the Western Regions with Hyecho (The National Museum of Korea, 2011).

8. Eun-su Cho, ‘Various Recensions of the Brahma’s Net Sutra Concentrating on the Tripitaka Koreana and Dunhuang Manuscripts’ (in Korean), Pojo Sasang 32 (2009): 183, 187 (English Abstract).

9. Yon-Sil Jeong, ‘A Comparative Study of the Chinese Character Variants in the Diamond Sutra Found in the Tripitaka Koreana and the Dunhuang Manuscripts’, Studies on the Tripitaka Koreana and its Corresponding Dunhuang Manuscripts: Their Recensions, Adaptation, and Changes (The Proceedings of the Kyujanggak International Conference, 2009), 278.

Accounts of Silla in Dunhuang Manuscripts

Kim Sang-hyun

Buddhist monks from Silla (57 BC–AD 935) began travelling to Central Asia and India from the seventh century. Some monks reached Tang China (618–907) by sea, while others followed the routes later known as the Silk Road to reach their destinations. They visited sacred Buddhist sites in Central Asia, and studied the teachings of the Buddha in Nālandā, India.

None of these monks returned to Silla after their pilgrimages, but their passion for seeking the Dharma and their adventurous spirit paved the way for important figures such as Hyecho 慧超 (704–87) in the late eighth century. Some of the monks transmitted knowledge of Silla as they passed through Dunhuang. Examples of documents written by Silla monks found at Dunhuang include Wonhyo’s 元曉 (617–86) Daeseung gisinnon so 大乘起信論疏 (Commentary on the Awakening of the Mahāyāna Faith) and Hyecho’s Wang ocheonchukguk jeon 往五天竺國傳 (A Travel Account to the Five Indian Kingdoms).

Our understanding of Wonhyo’s commentarial literature from the Dunhuang collection has been improved by a recent paper by Ding Yuan.1 Five Dunhuang fragments of the text were used in this research: Or.8210/S.7520 from the British Library; Dx-16758, Dx-8241B, and Dx-824 from the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in St Petersburg; and BD12261 from the National Library of China. Ding concludes that four different versions existed, and that all were transcribed between the eighth and tenth centuries. Also it has been confirmed that Wonhyo’s Commentary on the Awakening of the Mahāyāna Faith, influenced Tan Kuang’s 曇曠 (c.700–88) version Dasheng qixinlun guangshi 大乘起信論廣釋 (The Extensive Explanation of the Awakening of the Mayāhāna Faith) that circulated in the Dunhuang area in the late eighth century. Wonhyo authored more than one hundred texts, most of which were transmitted to Tang China, with a few reaching as far as India in the case of the Sipmun hwajaengron 十問和諍論 (The Reconciliation of Disputes in Ten Aspects). When viewed in this context, the discovery at Dunhuang of fragments of Wonhyo’s commentary comes as no surprise.

Hyecho arrived in Tang China during the eighteenth year of King Seongdeok’s reign (702–37) in 719. At the beginning of his journey, he met the Indian monk Vajrabodhi in Guangzhou and became his disciple. Under the encouragement of his teacher, he set out for India in 723 in his thirties. Four years after leaving Guangzhou, Hyecho ended his pilgrimage in India and Central Asia, and in November 727, he reached the city of Kucha. His journey is described in his three-volume travelogue, A Travel Account to the Five Indian Kingdoms. In 1908, a copy of this text was discovered by Paul Pelliot in the Library Cave at the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang, and is now part of the Bibliothèque nationale de France collection (Pelliot chinois 3532). This manuscript found in the Library Cave was just one section of an original text 6,000 characters long. The signature of the author does not appear on this manuscript, but once scholars found that the text had been written by Hyecho, it justly aroused interest worldwide. This travel diary was considered to be a valuable resource, shedding light on the history, customs, religion, and politics of eighth-century India and Central Asia.

The existing Travel Account to the Five Indian Kingdoms begins from Hyecho’s account of travels in Eastern India. He walked northwest from the Ganges River valley in the Magadha region for one month and arrived at Kushinagar. He travelled south to Varanasi where he prayed at Bodhgaya’s Mahābodhi Temple. Hyecho then continued his journey to Central India. He prayed at the Buddha’s birthplace Lumbini, and travelled through Western and Southern India before returning to the north, crossing the Pamir Mountains, and finally arriving in Kucha via Kashmir. Hyecho stayed for next fifty years in Tang China until his death at the age of eighty, never returning to Silla. He devoted himself to the study and transmission of Esoteric Buddhism in China.

Kim Sang-hyun is Professor at Dongguk University.

NOTES

1. Ding Yuan, ‘Understanding the Discovered Dunhuang Copies of Silla Wonhyo’s Literary Works’, Critical Review for Buddhist Studies 7 (2010): 151–176.

Previously Unpublished Silk Road Manuscripts Now Available Online

Completion of Digitisation of Dunhuang Chinese Manuscript Fragments in the British Library (Or.8210/S.8401-13891)

The British Library.

The Dunhuang manuscripts at the British Library come from two visits of the archaeologist Aurel Stein to Dunhuang in 1907 and 1914 respectively. After being acquisitioned into the British Museum collections they were assigned unique manuscript numbers in the sequence, Or.8210/S.nn, S. standing for Stein. When Lionel Giles published his catalogue in 1957 there were numbers up to S.6980. Conservation resulted in over a thousand additional manuscripts becoming available for readers and the entire sequence, S.1-S.8181 was microfilmed, giving much greater accessibility. A couple of hundred more were conserved after this and subsequently microfilmed.

However, this was not the total collection. Many manuscript fragments had also been acquired by Stein but as crumpled-up balls of paper and in a very delicate and fragile condition. Conservators of the time did not feel competent or have the resources to deal with them.

This situation changed in the 1970s. By then the collection had been transferred to the newly-established British Library and more scholars from mainland China started to visit London to use the collections. In addition, the Library’s Oriental Conservation Studio under Peter Lawson made contacts with conservators at the National Library and other institutions in China and started a programme of exchange visits. In 1987 the British Library hosted the scholars Professors Zhang Gong and Song Jiayu from the Institute of History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. They came with a proposal to photograph the secular manuscripts and produce a facsimile edition.

At the same time, with the newly acquired conservation skills and links, a project started to flatten and conserve the remaining fragments before photography, led in the Library by Dr Frances Wood. This involved long visits from Chinese conservators: Du Weisheng, Zhou Zhiyuan, Shao Zhuangren, Dai Liqiang, Gu Jun and Zhang Ping, and took several years to complete. It resulted in 5880 more manuscripts becoming available for study. The fragments, numbered Or.8210/S.8401 to S.13891, were encapsulated inside Melinex and stored in folders, enabling easy storage and access.

The first volume of the resulting facsimile edition was published in 1990, and the fifteenth and final index volume appeared in 2009. At the same time two scholars, Professors Rong Xinjiang and Fang Guangchang, were able to start work on producing catalogues of material not covered by Giles’s catalogue.

Professor Rong’s single-volume catalogue of the non-Buddhist material appeared in 1994, complementing the facsimiles. Professor Fang Guangchang had a much larger task to deal with the much greater number of Buddhist text fragments and the first volume of his multi-part catalogue appeared in 2000. Since then he has decided to amalgamate his work into an overall catalogue of the Dunhuang Buddhist material and has also been working on a facsimile of the British Library Buddhist material taken from the early microfilms.

IDP, which had been founded in 1993 with the aim of increasing access to the collections, had started mass digitisation of the Dunhuang manuscripts in 2001 following a large grant from the Mellon Foundation. Work concentrated initially on the scrolls — there are now over 40,000 images of these online. However, the necessity for conservation work on the scrolls and the lack of resources to keep up with the digitisation demands, meant that work also started on the fragments in the folders to regulate the digitisation workflow. This work accelerated in 2009 thanks to a grant for digitisation from the Research Institute for Korean Studies, the University of Korea, and with the visit of an intern, Kim Yichon, who helped IDP with the photography.

Rachel Roberts has been leading the work for IDP and thanks to her efforts and those of her colleagues, notably Abby Baker, the work has now been completed successfully. As of June 2011, all the 6136 manuscript fragments — over 13,000 images — are on IDP and thus freely available online for the first time. Efforts will now concentrate on fundraising for further conservation resource to enable the completion of digitisation of the remaining scrolls and to achieve the virtual reunification of all the manuscripts from the Dunhuang cave.

The Library has to thank numerous sponsors who have made this work possible, including The British Council, The Leverhulme Trust, The Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation, The Research Institute for Korean Studies, K C Wong Foundation, The Sino-British Fellowship Trust, and The British Academy.

Following Stein’s Dreams in Afghanistan

Afghanistan at the Heart of the Silk Road

Treasures from the ancient Bactrian kingdom — in what is now northern Afghanistan — recently moved from London on another leg of their worldwide exhibition schedule. In the exhibition catalogue, Afghanistan is billed as the crossroads of the Silk Road and the rich treasures on display as showcasing the cultural products resulting from this strategic position. Although Afghanistan has long been a region divided and fought over by neighbouring powers, it has also produced its own kingdoms and empires with rich and unique cultural mixes. It was this that attracted the scholar and explorer Aurel Stein (1862-1943). Yet it was not until his death — within a week of his arrival in Kabul at the age of 80 — that he was ensured an enduring link with a country he had longed to visit since childhood: he was buried in the British Cemetery (see below). The British were hardly in favour in Afghanistan and despite several attempts to get permission to visit, Stein had been thwarted throughout his life.

Centre: Looking across the Amu Darya at Sarhad, Afghanistan.

Right: Visitors leaving the exhibition in the Queen’s Palace, Kabul.

‘Your Excellency will dissuade him.’

Stein’s initial attempt to visit came in 1902 following his first expedition to Chinese Central Asia. After elicting the support of Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India from 1898 to 1905, and also, he thought, the Indian Foreign Office, he wrote to a friend that he planned to start for Herat following his return from England, ‘the fulfillment of a dream I had since I was a boy’

(Mirsky 1977, 202). He explained its attractions to him as a scholar of Iranian and Indian cultures:

‘From Bactria, the traditional home of Zoroaster’s religion and one of the oldest centres of civilization in Asia, there were derived those elements of unmistakably Iranian (Old Persian) origin which meet us in the earliest extant remains and records of North-Western India. After the invasion of Alexander the Great, Bactria, under Greek rulers, became the seat of a remarkable Hellenistic culture…’

But his optimism was misjudged: King Habibullah (r.1901-19) refused the application from Lord Curzon on Stein’s behalf:

‘I cannot in any way advise the said Doctor to carry out his intentions.’

Stein’s childhood dreams had to wait.

In the Footsteps of a Korean General

On his second expedition to Central Asia in 1906 Stein managed an initial brief foray, King Habidullah being more obliging and providing him with an armed escort to cross the Hindu Kush into the Pamirs and the Afghan Wakhan valley and to follow the waters of the Amu Darya (Oxus) up to the border of China. Stein did not squander this opportunity and sought to identify and survey places named in the historical sources. One of these was a fort that Stein associated with a battle between Chinese and Tibetan armies in 747. At this time the Chinese were employing generals of non-Chinese ethnicity for their border forces, believing them less likely to rebel. General Gao Xianzhi (Ko Sōnji) was of Korean (Goguryeo) descent. He suceeded where his predecessors had failed, defeating Tibetan forces and pursuing them south over the treacherous Darkot Pass to take the mountain kingdom of Yasin (in present-day Pakistan), thus enabling the Chinese to control the trade routes south into India.

Further Prevarications

Stein’s hopes were raised again in 1912 by Lord Hardinge, successor to Curzon as Viceroy from 1910-16, who agreed to support another request to the Amir. A letter was sent with a copy of Steins’s account of his second expedition, Ruins of Desert Cathay. The Amir was less abrupt this time, but the result was the same, a refusal.

It was no different in 1922. Again, Stein had the support of the British Viceroy and, he believed, that of the French archaeologist and long friend, Alfred Foucher (1865-1952). There was also a new regime in Afghanistan, King Habibullah having been assassinated.

However, Stein’s reservations about Foucher’s sincerity were substantiated when he discovered his erstwhile friend had been invited to set up a French archaeological mission and that Stein was not part of this: ‘Bitter as is the fresh failure of old hopes, it has not found me unprepared.’

Afghan Records in the British Library

Despite Stein’s failure to acquire archaeological spoils, Afghanistan’s geographical position between British India and the Russian empire ensured the British amassed considerable resources covering both ancient and modern Afghanistan. Most of these are now held in the British Library and include political archives material from the India Office Records, private papers from visitors, such as Charles Masson (James Lewis, 1800-1853, considered the first ‘archaeologist’ in Afghanistan), maps both from the India and Foreign Offices, and prints, drawing and photographs from the early nineteenth century onwards.

Lesley Hall’s 1981 Brief Guide gave an indication of the range and wealth of these materials and they have been used by a number of scholars and others – for example, the restoration by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) of the enclosure to Babur’s tomb in Kabul was based largely on drawings made by Masson in the early 1830s. A British Library proposal by John Falconer for an exhibition in Kabul of digital prints of historical images of Afghanistan coincided with a similar initiative under consideration by AKTC and the two organisations subsequently worked in partnership to bring this about.

Bringing Material to Afghanistan

The exhibition, largely funded by a grant from the UK World Collections Programme, was held at the Queen’s Palace in Babur’s Garden, Kabul in 2010 and received over 16,000 visitors. It then moved to the Chahar Suq cistern in Herat — also recently restored by the AKTC — and is now on permanent display in the new museum in the Citadel of Herat. A duplicate set of study prints were presented by the Library to Dr Muneer, Director of the National Archives in Kabul by John Falconer in 2011.

Falconer and Whitfield used visits to Kabul in 2010 and 2011 to make initial contact with Professor Amin, Chancellor of Kabul University (KU) and others, to discuss potential collaboration both for developing resources for use in teaching and research, in conjunction with the Afghanistan Centre at the University, and in offering professional development for faculty. They also discussed collaboration in areas of conservation, digitisation and cataloguing with Professor Muneer.

The Library and Kabul University were subsequently awarded an INSPIRE grant from the British Council ‘to make accessible the unique holdings in the British Library on sources relating to Afghanistan from mid-eighteenth to twentieth centuries’

, working together with the National Archives (NA). Faculty and staff from KU and the NA will be involved in the research and preparation of this resource, spending periods in London.

References:

Mirsky, Jeannette. Sir Aurel Stein, Archaeological Explorer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Hall, Lesley. A Brief Guide to Sources for the Study of Afghanistan in the India Office Records. London: India Office Library and Records, 1981.

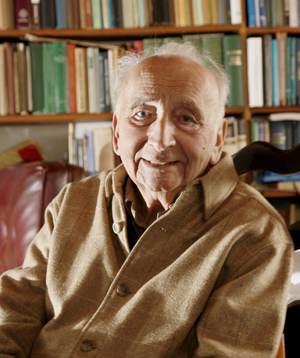

Denis Sinor 1916–2011

Denis Sinor was a revered name to a young scholar of western China and Central Asia. His publications in the 1970s were ambitious and often provocative. When I started work on the British Library collections of Aurel Stein, there were more resonances. Like his compatriot, Sinor had received a wide-ranging education in several European countries, including the UK and, like Stein, was versed in many languages.

In 1997 I finally had the chance to meet Sinor, inviting him to a seminar organised by IDP in July 1997 (35th ICANAS), to give a paper on his time with Paul Pelliot, the great French Sinologist, who had been his professor during his studies in Paris. Sinor charmed the audience with his account, where gossip and cuisine figured as much as scholarly debate.

Sinor held numerous positions but one he particularly prized was that of Secretary General of the Permanent Inner Altaistic Conference (PIAC), held from 1960 to 2007. During this period the annual conferences continued, several being held in Eastern Bloc countries during the Cold War: he used his languages, erudition and charm to good effect.

Indiana University, where Sinor went in 1962, provided a place him to thrive: he stayed there for the rest of his life. But he was never deskbound: he continued to travel widely, and not only throughout Central Asia and the Turkic world: he reached the North Pole in 2004. He only slowed down in his later years. At one of our final meetings in London I asked him if he missed travelling in Central Asia. With his usual aplomb he replied that it was just as pleasurable — and much more comfortable at his age — to drive in a large car with good suspension across the States, preferably with a female companion. He will be missed.

Susan Whitfield

Publications on Korea and the Silk Road

Silk‘ûrodû misul: Chun-gang Asia-esô Han’guk-kkaji

실크로드미술: 중앙 아시아에서한국까지

(Silk Road Art: From Central Asia to Korea)

Kwôn Yônggp’il 權寧弼

Seoul: Yôrhwadang, 1997

318 pp.

ISBN: 9788930110501

Silk Road and Dunhuang: Journey to the Western Regions with Hyecho

Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2010

ISBN: 9788993518153

This catalogue accompanies the exhibition of the same title held at the National Museum of Korea from December 2010 to March 2011. The Museum borrowed over 200 objects from institutions worldwide, including the Travel Account to the Five Indian Kingdoms, written by Hyecho in the eighth century, and now housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Pelliot chinois 3532). See above for more information on this manuscript.

Hyechoui Wangocheonchukgukjeon

혜초의 왕오천축국전

(A Travel Account to the Five Indian Kingdoms)

Jeong Su-il 정수일

Seoul: Hakkojae, 2008

339 pp.

ISBN:9788956250748

So yok mi sul: Kuk lip cuñ añ pak mul koan so cañ

西域美術 : 국립중앙박물관소장

(Arts of Central Asia)

Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2003

331 pp.

ISBN: 9788990382122

This publication is a catalogue of the Arts of Central Asia exhibition held at the National Museum of Korea from December 2003 to February 2004. The catalogue features captions provided in Korean, Chinese and English, and essays by Kwon Young-pil, Idiris Abdurusul, and Min Byuong-hoon.

History and Culture of Central Asia

Young-pil Kwon & Ho-dong Kim (eds)

Seoul: Sol, 2007

467 pp.

ISBN: 9788981338695

Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea, and Japan

Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky

Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 2000

249 pp.

ISBN: 9780761816706

Silkeurodeuwa Hanguk Munhwa

실크로드와 한국 문화

(Silk Road and Korean Culture)

International Association for Korean Studies

Seoul: Sonamu, 2000

456pp.

ISBN: 8971395346

Silk‘û Rodû esô on ch‘ônbulto: Kungnip Chungang Pangmulgwan sojang Chungang Asia pyôkhwa

실크 로드 에서 온 천불도 : 국립 중앙 박물관 소장 중앙 아시아 벽화

(Thousand-Buddha Murals from the Silk Road: Central Asian Murals at the National Museum of Korea)

National Museum of Korea, 2006

41 pp.

ISBN: 9788995807316

The Dreams of the Living and Hopes of the Dead: Goguryeo Tomb Murals

Ho-Tai Joen

Seoul: Seoul National University Press, 2007

180 pp. US$40

ISBN: 9788952107299

Seoul National University Press Website

This book provides an analysis of the technology used in the Goguryeo tomb murals, and shows how the murals yield much information regarding views of the afterlife, religion and cosmos, and daily life in Goguryeo.

Are all Warriors Male? Gender Roles on the Ancient Eurasian Steppe

Katheryn M. Linduff and Karen Sydney Rubinson

Lanham: AltaMira Press, 2008

270 pp. US$80

ISBN: 9780759110731

AltaMira Press Website

This book contains a chapter by Sarah Milledge Nelson entitled ‘Horses and Gender in Korea: The Legacy of the Steppe on the Edge of Asia’, 111-127.

Currents and Countercurrents: Korean Influences on the East Asian Buddhist Traditions

Buswell, Robert E., Jr

Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005

304 pp. US$27

ISBN: 9780824831790

University of Hawai‘i Press Website

IDP Centre Staff Publications

Tibet: A History

Sam van Schaik

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011

324 pp. £25/US$35

ISBN: 9780300154047

Yale University Press Website

Works of the Orientalists during the Siege of Leningrad (1941-1944)

Труды востоковедов в годы блокады Ленинграда (1941—1944)

Irina F. Popova (ed.)

Moscow, Vostochnaya Literatura

Publishers, 2011

343 pp.

ISBN: 9785020364660

Vostochnaya Literatura Website

Der alttürkische Kommentar zum Vimalakirtinirdesa-Sutra

Yukuyo Kasai

Turnhout: Brepols, 2011

237 pp. €70

ISBN: 9782503541570

Brepols Website

Mani’s Psalms. Middle Persian, Parthian and Sogdian Texts in the Turfan Collection

D. Durkin-Meisterernst, E. Morano (eds.)

Turnhout: Brepols, 2010

380 pp. €80

ISBN: 9782503528878

Brepols Website

Prajñāpāramitā Literature in Old Uyghur

Abdurishid Yakup

Turnhout: Brepols, 2010

300 pp. € 120

ISBN: 9782503528885

Brepols Website

Journals

Bulletin of the Asia Institute No. 20, 2010

Edited by Carol Bromberg

Contents include:

- Bardiya and Gautama: An Achaemenid Enigma Reconsidered, M. Rahim Shayegan

- Iranian Gods in Hindu Garb: The Zoroastrian Pantheon of the Bactrians and Sogdians, Second-Eighth Centuries, Frantz Grenet

- Reflections on the Gandhara Bodhisattva Images, Pratapaditya Pal

To order: US$75 + shipping. For earlier volumes see website:

http://www.bulletinasiainstitute.org

Email: [email protected] or [email protected]

Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology Volume 4, 2009-10

Edited by Dr. Lilla Russell-Smith and Dr. Judith Lerner

Contents include:

- The Ossuary from Sangyr-tepe (Southern Sogdiana): Evidence of the Chionite Invasions, Frantz Grenet and Mutalib Khasanov

- Early Tarim Basin Buddhist Sculptures from Yanqi (Karashahr): A New Dating, Khau Ming Rubin

- Reconsidering Early Buddhist Cave-making of the Northern Wei in Terms of Artistic Interactions with Gansu and the Western Regions, Katherine R. Tsiang

- Some Remarks on the Headgear of the Royal Turks, Sören Stark

- Peacocks under the Jewel-tree–New Hypotheses on the Manichaean Painting of Bezeklik (Cave 38), Gábor Kósa

- The Tibetans in the West, Part II, Philip Denwood

- Central Asian Manuscripts ‘Are Not Worth Much To Us’: The Thousand-Buddha Caves in Early Twentieth-Century China, Justin Jacobs

To order: €60 + shipping, please see:

Brepols Website

Exhibitions

Images of Lord Buddha: Buddhist Art in Asia

Residenzschloss Oettingen in Bayern

Branch of the Munich State

Museum of Ethnology

Schloßstraße 1, 86782

Oettingen in Bayern, Germany

15th April, 2011 – 5th February, 2012

Venue Information

This exhibition shows the development of the depiction of the Buddha starting with the earliest images in human form from Gandhara and Mathura, before moving through Sri Lanka, China, Japan, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Laos and Cambodia.

The Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan: Art of Gandhara

Asia Society Museum, New York

9th August – 30th October, 2011

Exhibition Website

This exhibition features sculptures, architectural reliefs and works of gold and bronze from Pakistan, most of which have never been exhibited before in the United States.

The majority of works in the exhibition are on loan from the National Museum in Karachi and Central Museum in Lahore. Comparative works are included from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Asia Society Museum, and private collections.

IDP Worldwide News

IDP Japan

The Ryukoku Museum opened in front of the Nishi Hongwanji Temple in Kyoto on 5th April 2011. Hailed in the press as the world’s first comprehensive museum on Buddhism, Ryukoku Museum presents the origins and history of Buddhism in India, and its transmission through Asia and evolution in Japan. The permanent galleries of the museum focus on Buddhism in Asia, and Buddhism in Japan. Temporary exhibitions will display artefacts from the collection of Ryukoku University, including items from the Otani collection.

The museum aims to present Buddhism to different audiences, ranging from the general public to students and scholars. The displays use sound and image to help convey the ‘fun’ of Buddhism, in an attempt to make it more accessible to a wider range of people, according to the Museum Director Akira Miyaji.

A special exhibition entitled Śākyamuni and Shinran is being held to commemorate the opening of the museum. Over 600 Buddhist artefacts and documents from Japan and other Asian countries will be on display. The exhibition will run until 25th March 2012, to coincide with the 750th anniversary of the passing of Shinran.

The first half of the exhibition focuses on the life and teachings of Śākyamuni, Mahāyāna Buddhism in Gandhāra, and the development of Pure Land Buddhism, while the second half tells the story of Buddhism in Japan, the spread of Pure Land Buddhism, the life of Shinran and his teaching.

One of the museum’s highlights is a full-size digital reproduction of Buddhist murals of cave 15 of the Thousand Buddha Caves at Bezeklik near Turfan, western China.

IDP Germany

Markus Reinsch has started work at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Science and Humanities on inputting data on the Turfan Tocharian fragments into the IDP database. He is also manipulating the images, and uploading to the IDP database. The new scans of the THT slides was made possible by funding from the Göttingen Academy of Sciences.

IDP Sweden

A delegation from Stockholm including Håkan Wahlquist, Ann Olsén, and Magnus Johansson from the Museum of Ethnography, and Birgit Schlyter and Johan Fresk from the University of Stockholm visited IDP UK on 17th–18th March 2011 to discuss setting up IDP Sweden after receiving funding from the Bank of Sweden to begin digitisation of the Swedish Central Asian collections.

IDP China

Beijing

The exhibition Treasures of the Western Regions: Xinjiang Historical Documents, partially supported by IDP China staff, ran from 27th January-10th March 2011 at the National Library of China. This exhibition was the continuation of the one ran 20th August-20th October 2010 at the Xinjiang Museum, Urumqi. More than sixty manuscripts and coins excavated from Turfan, Khotan and other archaeology sites were displayed, including items written in Chinese, Sanskrit, Kharoṣṭhī, Sogdian, Kuchean, Turkic, Uighur and other languages and scripts. Treasures of the Western Regions: Catalogue of the Xinjiang Historical Documents Exhibition was published by the NLC press in early 2011.

IDP Beijing marked up Paul Pelliot’s catalogue, Catalogue of Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (巴黎圖書館敦煌寫本書目), which was translated into Chinese by Lu Xiang. The catalogue has 1511 items, including a record of Pelliot chinois 2001–3511, and 84 notes written by the translator Lu Xiang. IDP Beijing also marked up Dr. Huang Yongwu’s catalogue, Catalogue of Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Beiping Collection (北平所藏敦煌漢文卷子目錄) in the first half of 2011. The catalogue has 8679 items, and each item includes a Chinese title for the Dunhuang manuscripts in NLC collection.

Dunhuang

The Dunhuang Academy (DHA) held the first of a series of activities introducing Dunhuang and cultural heritage to schoolchildren across China at Juqian Street primary school and five other schools in Changzhou in Jiangsu province. Over the previous years, primary schoolchildren from Changzhou have raised money for the DHA to use for the protection of the Mogao Caves.

The aim of these activities is to give schoolchildren an awareness of a range of issues such as the importance of history and cultural heritage, protecting the environment, and preserving cultural heritage for future generations. The DHA hopes that these activities will inspire schoolchildren to take an interest in Dunhuang and its history as part of their own heritage.

IDP France

Dunhuang Conference in Paris

On 14th–16th June 2011 a conference was held in Paris to present recent research from China and France in Dunhuang studies, with the title Rencontres franco-chinoises sur les études de Dunhuang: Actualité de la recherche et publications récentes. The event was organised by the Centre de Recherche sur les Civilisations de l’Asie Orientale (CRCAO) and the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), and coordinated by Kuo Liying, Eric Trombert and Costantino Moretti. The talks were held at the Collège de France and Maison de l’Asie, where participants principally from Chinese and French institutions reported on their current research and forthcoming publications. The first panel on 14th June commemorated three prominent scholars and veterans of Dunhuang studies, all of whom passed away this year: Duan Wenjie 段文杰 (1917–2011), Wu Chi-yu 吳其昱 (1915–2011) and He Shizhe 賀世哲 (1930–2011). Later presentations focused on more specialized subjects, ranging from digital resources to large-scale publication projects, from archaeological surveys to the study of medieval manuscripts.

Among the speakers giving papers at the conference were Chinese guests Fan Jinshi, Peng Jinzhang and Zhang Xiantang of the Dunhuang Academy; Shi Jinbo and Yang Zhishui of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences; and leading scholars from France, including Jacques Gernet (Collège de France), Jean-Pierre Drège (École Pratique des Hautes Études EPHE-CRCAO), Nathalie Monnet (Bibliothèque nationale de France), Kuo Liying (EFEO-CRCAO), Catherine Despeux (INALCO-CRCAO), Eric Trombert (CNRS-CRCAO), Laure Feugère (Musée Guimet), Costantino Moretti (EPHE-CRCAO). In addition, two researchers from the UK, Helen Wang (British Museum) and Imre Galambos (IDP, British Library), also presented the results of their recent work.

Following the presentations, on the afternoon of the second day, participants visited the Musée Guimet where Valérie Zaleski showed them textile paintings and movable types acquired from Central Asia by Paul Pelliot. On the third day Nathalie Monnet showed delegates some of the most interesting Dunhuang manuscripts in the Pelliot collection at the BnF. These two visits provided a rare opportunity to examine in person treasures from the Dunhuang Library Cave.

Imre Galambos

IDP Russia

Professor Irina Popova ran a session on 21st March 2011 focused on Dunhuang manuscripts in the collections of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM), as part of the series on methodological issues of reading Asian manuscripts.

In May 2011, Professor E.I. Kychanov of the IOM was given the S.F. Oldenburg Award of the Government of St Petersburg in the area of science and technology for his outstanding achievements in Central Asian studies and contribution to deciphering the Tangut script and texts. The authorities of the IOM, and all his colleagues warmly congratulate Dr Kychanov on his achievement.

On 4th May 2011, a seminar on genre in Asian literatures took place at the IOM. Six young scholars and doctoral students gave short presentations: Dr S. Kh. Shomakhmadov (Issues of the Genre Attribution of Buddhist Narrative Literature. A Khotanese Manuscript of Avadana on Gandi in the collection of the IOM), Dr V. P. Ivanov (Genre in Ancient Sanskrit Literature), M.A. Redina (Literary Genres in Ancient Mesopotamia), V.V. Shchepkin (Genres in Japanese Literature), D.O. Nosov (Issue of Genre in Medieval Mongolian Literature), and Dr A.V. Zorin (The Formation of Genres of Tibetan Literature).

The IOM held an exhibition of selected treasures from its collections for participants of the fifth St Petersburg International Economic Forum (16th–18th June, 2011), including examples from the Dunhuang and Kharakhoto collections.

IDP UK

People

We were very sorry to say goodbye to Barbara Borghese, who left IDP at the end of March 2011. Barbara started at IDP as a conservator funded by the Mellon Foundation in 2001, becoming IDP European Project Coordinator in 2006. We wish her luck in her new role as editor at News in Conservation.

Dr Shouji Sakamoto, from Ryukoku University, Kyoto began a one-year project at IDP UK in January. He is using a scanning electron microscope to collect data on the morphology of paper of Dunhuang manuscripts in the British Library Stein collection. Dr Sakamoto will take sample images of the paper which he will upload to the IDP database. He will also carry out XRF analysis of pigments on the manuscripts, working together with Dr Renate Noeller in Berlin.

Dr Catrin Kost started work on 11th April 2011 cataloguing the Stein 3D objects at the British Museum, and coordinating their digitisation with IDP. Rachel Roberts of IDP is photographing this collection at the British Museum. Researchers from China and India funded by the World Collections Programme will be arriving in London over the second half of 2011 to help with data input and cataloguing of this collection.

Research

One of IDP’s longest-running research projects, on the palaeography of the Dunhuang manuscripts, is now complete after five years. The project, generously funded by the Leverhulme Trust, co-ordinated research into the writing styles, book forms and social conventions of Tibetan and Chinese manuscripts from the fifth to tenth centuries AD. The project resulted in many articles in academic journals, the monograph Manuscripts and Travellers, a tool for isolating individual letters or characters from digital images, and an online resource for learning to read Tibetan and Chinese manuscripts. The long-term influence of the project continues in IDP’s ongoing collaborative work in palaeography and codicology.

Collaboration

Susan Whitfield and Alastair Morrison visited Delhi to attend a conference on Kumārajīva at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) on 3rd–5th February 2011; Alastair Morrison gave a paper on manuscripts relating to Kumārajīva in the BL collections. During the visit, funded by a Connections through Culture grant from the British Council, they led a workshop with local MA students majoring in conservation, museology, history of art, and fine arts at the National Museum Institute on resources on the Central Asian collections and IDP. Professor Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst, Director of the Turfan Research Group in Berlin, contributed to the workshop. They also met with colleagues at the National Museum and spoke to officials at the Ministry of Culture regarding further collaboration, including a proposal to hold a series of conservation workshops at the National Museum Institute starting in spring 2012.

On 3rd–4th February 2011, Sam van Schaik attended the editorial meeting of the Old Tibetan Documents Online (OTDO) in Kobe, Japan. The OTDO website contains transliterations of Tibetan texts from Dunhuang, and will soon be expanded to include inscriptions and material from other Central Asian sites. The editorial group discussed developments in the OTDO website, and agreed on closer links between IDP and OTDO. Already, OTDO’s transcriptions are linked IDP’s images and catalogues, and vice versa.

Cataloguing

New transliterations of the British Library’s Sanskrit fragments by leading scholars in the field have just been put online on the IDP website. Go to the catalogue search page to browse the transliterations. This work is the result of a collaborative project, headed by Professor Seishi Karashima, between IDP and the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology in Tokyo. The manuscripts have been digitized by IDP, so the transliterations may now be viewed alongside high-quality colour images.

Download this newsletter as a PDF

This digital version of IDP News is based on the print version of the newsletter and some links and content may be out of date.

This issue, No. 36-7, was published Winter-Spring 2010-11.

Editor: Alastair Morrison

Picture Editor: Rachel Roberts

ISSN 1354-5914

All text and images copyright their creators or IDP, except where noted. For further information on IDP copyright and fair use, please visit our Copyright page.

For further information about IDP please contact us at [email protected] or visit our Contact page.