Shaping the Stein collection’s Dunhuang corpus (1) Wang Yuanlu: the first ‘curator’

The British Library, British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum and National Museum of India hold a significant amount of manuscripts and other pieces acquired by Marc Aurel Stein (1862–1943) at Dunhuang in 1907 and 1914. The history of these items is closely linked to the discovery of Cave 17 at the Mogao Caves complex, in Gansu province. This blog post focusses on Wang Yuanlu 王圓籙 (1850–1931), the man who discovered the small walled-up cave. It is the first of three articles exploring the way in which the Stein Collection’s Dunhuang corpus was shaped.

Wang, keeper of the Mogao Caves and guardian of Cave 17

Originally from Hubei, Wang Yuanlu 王圓籙 (1850–1931) moved to the Mogao Caves around 1899 (Wang, 2007: 3–6). This Buddhist site, once an important centre on the Eastern Silk Roads, had remained a place of worship but had fallen into relative disuse. Wang started to raise funds for the restoration and upkeep of the caves. In June 1900, as he was clearing the sand from the corridor of a large cave-temple, Wang Yuanlu stumbled upon the concealed entrance to a small room. The room, now known as Cave 17 or the ‘Library Cave’, contained tens of thousands of manuscripts, printed documents, paintings and textiles.

These materials date roughly from the 4th to the 11th centuries. Probably sealed up at the beginning of the 11th century, they had remained hidden for nearly one millennium. Wang alerted the authorities but no measures were taken until 1904, when orders came from the provincial government in Lanzhou to ensure that Cave 17’s contents were back in situ and safely guarded. This task was somehow delegated to Wang Yuanlu, who put a locked door on the entrance of Cave 17 and kept the key. Wang thus became the keeper of the newly found hoard, which nobody could access in his absence (Stein, 1912: 29; Pelliot, 1908: 505).

From 1900 onwards, Wang Yuanlu gave several items from Cave 17 to local officials. He chose well-preserved manuscripts, which were made of fine paper and had beautiful calligraphy, as well as several remarkable silk paintings (Rong, 2013: 90–1). This shows not only that he was able to select the most visually striking specimens, and also that he was probably aware of the value of the cave’s contents. Through the process of handpicking attractive examples, Wang Yuanlu would have gone through quite a lot of materials. In addition, we know that he emptied the room and later placed all the bundles back in (Stein, 1921: 808–9), gaining familiarity with what was inside.

Wang was embedded in the local Buddhist community. When the explorer Marc Aurel Stein first visited the site in March 1907, Wang Yuanlu was absent and had locked Cave 17. However, a young monk showed Stein one of the Chinese scrolls from the cave. The “beautifully preserved” manuscript had been lent to his spiritual master, a Tibetan lama, in order to give “additional lustre” to his small private chapel (Stein, 1921: 801–2). This proves that Wang agreed to let the resident monks use items from Cave 17 for their ritual practices. Stein later observed that they shared the guardianship of the Mogao Caves and lived in harmony with Wang Yuanlu (Stein, 1912: 29).

Rong Xinjiang highlighted that hundreds of manuscripts and paintings were possibly dispersed between the discovery of Cave 17 and 1907 (2013: 84–102). Yet, it is Wang’s transaction with Stein in 1907 that marked the scattering of the newly found hoard on a large-scale. We will now see that Wang Yuanlu set the terms of their exchange.

Wang and Stein

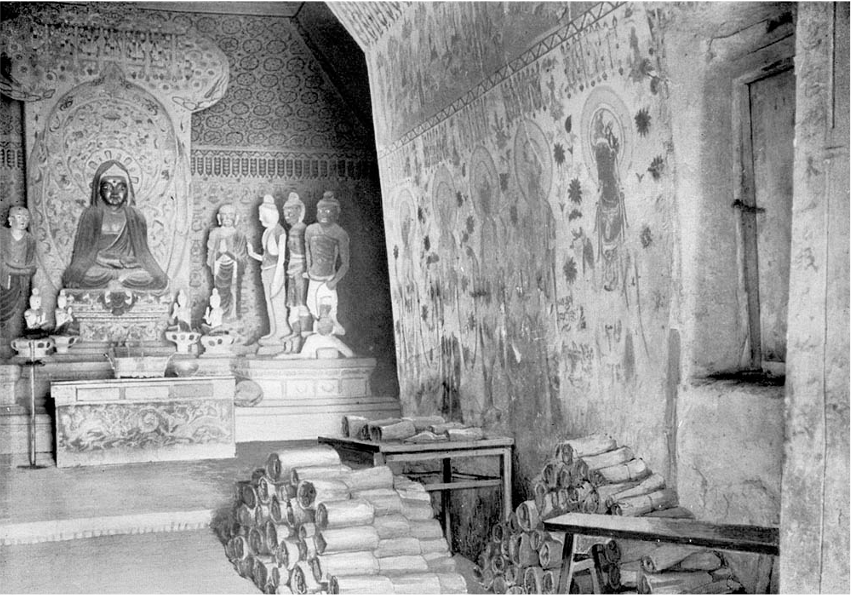

Marc Aurel Stein came back to the Mogao Caves in May 1907. This time, he got to meet Wang, who only allowed him to quickly look inside Cave 17. From his rapid examination, Stein reported that there were two categories of bundles: the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles, filled with manuscripts in various languages and formats, paintings and ex-votos; and the ‘regular’ bundles, which he assumed mostly contained Chinese and Tibetan Buddhist manuscripts (1921: 814).

The ‘regular’ bundles were sandwiched between two layers of ‘miscellaneous’ bundles. One layer was placed on top of the ‘regular’ bundles; another layer at the bottom was used to provide a stable basis for the piles of ‘regular’ bundles (Stein, 1912: 178–9). Wang Yuanlu had seemingly re-organised the bundles following an arrangement that he thought to be more appropriate and that possibly reflected his own appraisal of these materials. Indeed, it is quite telling that he started by presenting Stein with several of the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles. Stein remarked that Wang appeared to value these a lot less than the ‘regular’ monastic bundles (Stein, 1912: 178–9).

At no point during the process did Wang let Stein choose materials directly from the cave. He insisted on handing over each of the bundles that he retrieved himself from inside Cave 17. He was therefore able to guide the selection, by having already performed a form of sifting. The explorer spent several days looking through ‘miscellaneous’ bundles in order to extract any of the items that he found interesting (we will explore the content of these bundles in a separate blog post).

When Stein turned his attention to the ‘regular’ bundles, however, he was faced with a huge amount of resistance from Wang Yuanlu (Stein, 1921: 822). Wang explicitly stated that it would be impossible for Stein to purchase any of the ‘regular’ bundles. He explained that any deficiency in the piles of ‘library bundles’ would be noticed by his lay patrons and “lead to the loss of the position which he had built up for himself in the district by the pious labours of eight years and to the destruction of his life’s task” (Stein, 1921: 824).

Wang insisted that he needed to consult his patrons before making any further decision and set off to Dunhuang to beg for alms, having previously conceded to sale of around 50 ‘regular’ bundles plus all the content from the ‘miscellaneous’ bundles. We do not know what happened while Wang Yuanlu was away, but upon his return a week later he sold another 20 ‘regular’ bundles to Stein. It is likely that he may have sought the opinion of his patrons about selling the regular bundles.

Stein left Dunhuang at the beginning of June 1907, with 12 cases crammed with all his acquisitions. At the end of September 1907, he dispatched his secretary Jiang Xiaowan 蔣孝琬 (d.1922) to purchase more materials from Cave 17. Jiang’s expedition was a success, yielding another 230 of the regular bundles (British Museum Central Archives, CE 32/23/16/2).

In 1908, when Paul Pelliot (1878–1945) came to the Mogao caves, Wang Yuanlu sold him another significant portion of the manuscripts and paintings from the small cave. In 1910, the Qing Ministry of Education ordered the transfer of the remaining manuscripts to Beijing. In spite of this, Wang managed to hold onto several ‘regular’ bundles, which he sold to the members of the Otani expedition in 1912 and 1914, and to Stein when he visited the site again in 1914.

Conclusion

Wang Yuanlu, who took upon himself to act as the guardian of the Mogao Caves when he settled at the site, can also somehow be considered the first ‘curator’ or ‘keeper’ of Cave 17’s contents. For his subsequent actions, which resulted in the scattering of the manuscripts, paintings and other items deposited in the small room, he has been described either as a naïve fool or as a thief. Through Stein’s narrative, we can see that Wang was neither.

Wang Yuanlu truly set the conditions for their exchange and planned what bundles to deliver, focusing initially on the items he held in the lowest estimation. When he eventually decided to part with the ‘regular’ bundles that he valued the most, he seems to have done so in consultation with his patrons. This highlights Wang Yuanlu’s agency and demonstrates that he was instrumental in shaping the now so-called Stein collection.

Further reading:

British Museum Central Archives, Confidential report by Stein concerning the cache of ancient manuscripts at Dunhuang, CE 32/23/16/2.

Pelliot, P. “Une bibliothèque médiévale retrouvée au Kan-sou”, Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême Orient 8 (1908): 505-509.

Rong, X. Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, translated by Imre Galambos, Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2013.

Stein, M.A. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China, London: Macmillan, 1912.

Stein, M.A. Serindia: detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, etc., Volumes 2 and 4, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921.

Wang, J 王冀青. Guo bao liu san: Zang jing dong de gu shi 國寶流散:藏經洞的故事, Lanzhou: Gansu jiaoyu chubanshe, 2007.

If you have feedback or ideas about this post, contact us, sign in or register an account to leave a comment below