The Berlin Turfan Collection – Online

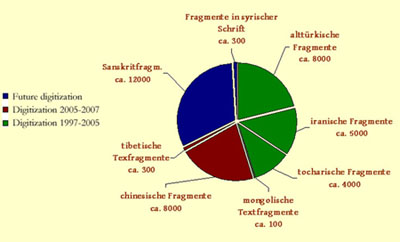

In summer 2005 the initial project to digitise the Berlin Turfan collection was completed. The project had three stages (October 1997-March 2000, April 2001-June 2003, July 2003-July 2005) and was primarily sponsored by the German Research Foundation. Starting in 1997, a staff of two (which included at different times Claudius Naumann, Ramin Shaghagi, Paul Emmerick, Götz König and Kati Brauchmann) digitised over 14,400 fragments, supervised by colleagues from the two Turfan research projects in Berlin. The project was based at the Berlin Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (BBAW), first in the Academy wing of the old building of the Berlin State Library and later, moving in with the Turfan research projects, in the main building of the Academy at the Gendarmenmarkt. The Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage with its Oriental Department and the restoration and conservation studios took an active part in the digitisation project. (After the reunification of Germany in 1990, the Turfan collections of BBAW were reunited and are now under the supervision of the Oriental Department of the State Library in Berlin – see IDP News 3.)

The Berlin State Library carried out the necessary restoration work on the fragments to be digitised, most preserved between two glass plates, and then photographed them to produce 35mm colour slides. The slides were then scanned to form the Digital Turfan Archive (DTA) (see above). This consists of 28,465 digital online images of around 8,500 Uighur and Chinese/Uighur fragments, around 5,000 Middle Iranian fragments, 100 Mongolian fragments and all fragments of the ‘Mainz’ collection. This archive of digitised fragments has been gratefully received by the international scholarly community as shown by the frequent requests for copies of the digitised material for scientific research.

In 1998 the Third IDP Conservation Conference was held in Berlin and the participants not only visited the archives of the Berlin Turfan collections, but also the small digitisation studio.

At the beginning of June 2005 a workshop sponsored by BBAW was organized in order to discuss the results of the first digitisation project, the experiences of which were summarized by Kati Brauchmann, and to sign an agreement of cooperation with IDP for a planned new project. This project consisted of the digitisation of Chinese, Tibetan, Syriac and Sanskrit fragments in the Berlin Turfan collection (see IDP News 26). During the first project short notes were added to the images of only some of the fragments. To obtain more detailed information concerning the content, publications etc. of the fragments, it was necessary to consult published reference works or catalogues. These limitations were due to too few staff, strict timetables and catalogues not being available at the time of data input. The international collaboration with IDP was launched to avoid these limitations and to join our digitisation project with other international projects on the digitisation of fragments collected on the Silk Road. Thanks to this collaboration the digital images of these texts will be presented with additional information in the IDP database, together with similar fragments preserved in other Central Asian collections. This additional information will be based in the main on the respectable number of catalogue volumes compiled for the Sanskrit, Chinese and Tibetan Turfan fragments and published in the series ‘Berliner Turfantexte’ and ‘Verzeichnis der Orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland’. Mazumi Mitani, Tsuneki Nishiwaki and Klaus Wille, who were or are still in charge of the compilation of these catalogue volumes, gave a detailed report on the around 8000 Sanskrit and 6000 Chinese fragments preserved in the Berlin Turfan collection. The papers are available online here.

Among the Chinese texts in Berlin are the remains of more than 40 scrolls and some large fragments. These fragments will require several single shots which have to be joined digitally afterwards for the presentation in the database. During the first project, the digitisation of the Chinese-Uighur fragments (Ch/U signatures), already more than 1,600 Chinese fragments with Uighur script on the verso part, were digitised. Since paper was very rare and valuable at the time, Uighur and other scribes used the empty verso side of Chinese texts to write on and so many fragments contain more than one language and script.

Thanks to the financial support of the German Research Foundation the second digitisation project was started in November 2005.In the first period of this, the remaining Chinese fragments – together with the Tibetan fragments – are to be digitised. Within the first 18-month period Kati Brauchmann and Barbara Meisterernst have been adding digital images and metadata of the Chinese and Tibetan Turfan fragments to the IDP database.

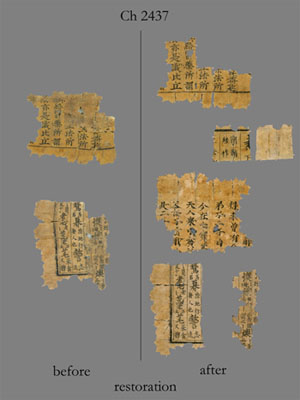

First, the shelf numbers and finding signatures of all Chinese fragments together with further information from the existing catalogue volumes, such as titles, measurements etc. were added. Within the first eight months more than 2500 digital images of Chinese fragments were produced and more than 1600 of them are already available online. A not inconsiderable number of Chinese fragments need restoration or conservation before photographing because of broken glass plates, folds in the paper, soiling of the paper, etc. These circumstances all compromise the legibility of the texts. In some special cases pages glued together have now been separated and have yielded new texts on their former inner sides (see for example the image to the left of the fragment Ch 2437 before and after restoration below). It is thanks to the additional financial support of the German Research Foundation within the framework of the digitisation project that we are able to strengthen our efforts in this field.

This project aims to provide digital images of all Chinese and Tibetan fragments stored in the Turfan collection together with identification of the fragments and bibliographical information if available and it will thus place the fragments together with the existing catalogue information at the disposal of the international scholarly community. In the last decade, the worldwide scholarly interest in the Chinese fragments preserved in the Berlin collection has increased immensely. After the publication of the two further volumes of the catalogue of the Chinese Turfan texts, compiled by Tsuneki Nishiwaki (a catalogue volume of 358 non-Buddhist Chinese fragments) and Kogi Kudara in cooperation with Toshitaka Hasuike and Mazumi Mitani (a catalogue volume of 1100 Chinese Buddhist fragments) we received many requests for photographs of these Chinese fragments from researchers in various countries, among them Prof. Masashi Oguchi and his team at Hosei University (Japan), Prof. Tokio Takata and Dr. Wang Ding at Kyoto University (Japan) and from the International Project of the Research of the Dunhuang Manuscripts with Medical Content under the direction of Prof. Catherine Despeux. Thanks to the progress being made in the digitisation of the Chinese fragments we are more and more able to offer high resolution digital images for their study.

As a result of the increased cooperation with IDP the BBAW now also hosts a German version of the IDP website (see below). Full searches in using German keyterms will shortly be implemented on this site.

Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky and the Politics of Russian Imperialism

Kyrill Kunakhovich

By the time of his death in 1888, Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky was one of the most famous and popular men in the Russian empire. In four journeys over the course of two decades, the explorer had traversed Inner Asia, a region comprising Western Mongolia, Eastern Turkestan, and Northern Tibet. He was the first European to reach many of these areas, and his original maps won him medals and acclaim from all leading geographical societies in Europe. To this day a range of the Kunlun Mountains bears Przhevalsky’s name, as do a number of local peaks and villages. Equally noteworthy are the explorer’s scientific accomplishments. Przhevalsky brought some 16,000 specimens of 1,700 botanical species back to St. Petersburg; he was also a skilled hunter and introduced Europe to numerous species of camel, yak, and other mammals. His best remembered discovery is perhaps the wild horse that shares his name – equus przewalskii, a wild, stocky equine of diminutive stature, thought to be a primary ancestor of European domesticated horses. This scientist-explorer is also familiar to every Russian schoolboy, since countless Soviet publications extolled Przhevalsky as ‘the first naturalist of Central Asia.’1

For Przhevalsky himself, though, as well as for the Russian patrons who encouraged and funded his journeys, the explorer’s role was political as much as scientific. Carried out at a time of imperial expansion, his expeditions charted a strategically vital territory on the border of the Chinese empire. Przhevalsky’s journeys also represented Russia’s desperate attempt to keep up with Western European powers by annexing lands on par with the recently colonized vastness of Africa. The explorer himself relished his political role, oftentimes ignoring geology and ethnography for the sake of military reconnaissance. To a much greater degree than Sven Hedin or Aurel Stein, Przhevalsky was a servant of the state, constantly reporting back to St. Petersburg and carrying out missions assigned to him by the Ministry of War. Here I analyze the political role of Przhevalsky’s journeys, using Przhevalsky’s published travel reports, his secret communiqués to the Russian General Staff,2 and contemporary Western scholarship. To what degree did political considerations motivate the explorer’s expeditions? How did political realities affect the course of his travels? What were Przhevalsky’s own attitudes towards international diplomacy, in which he played such a role?

In large measure, it was Russia’s political situation that first aroused Przhevalsky’s interest in Inner Asia. Born in 1839 in Smolensk — a provincial town 250 miles West of Moscow — the future explorer enrolled in the army at the age of sixteen (1855), prompted in part by Russia’s humiliating defeat in the Crimean War. Even at the height of his fame, the military would remain Przhevalsky’s primary identity. Throughout his expeditions he was attached to the Main Staff, the intelligence branch of the army; by the end of his life he had reached the level of major general and always wore his army uniform in public. When the Turkish War broke out in 1877 the explorer even volunteered for the front, though he was told that he was more useful to the army where he was — reconnoitering Chinese territory in Turkestan.

Przhevalsky’s fascination with Asia seems to have been inspired by David Livingstone and other European explorers, whose books he pored over. Their accounts of colonization established a pattern that he himself would try to follow; in the unexplored lands of Inner Asia Przhevalsky saw the potential territory of a vast Russian Empire no less grand than the British or the French. ‘Here we can still repeat the exploits of Cortez’, he wrote to a friend in 1873.3 As a colonizing power, Russia also had to act as a representative of Western culture and civilization. Like all European nations, it generously took upon itself the White Man’s Burden of educating the primitive nomads of Asia and ‘bear[ing] away in the name of civilization all these dregs of the human race.’4 The explorer’s mission was thus global as well as national, for ‘our military conquests in Asia bring glory not only to Russia; they are also victories for the good of mankind.’5

Such rhetoric reveals elements of Social Darwinism, a philosophy that was fast becoming popular in Russia in the 1870s, when Przhevalsky undertook his earliest expeditions. The explorer was convinced of Europe’s racial supremacy over the peoples he considered ‘savages’. After one victorious skirmish, he remarked, ‘such is the moral superiority of the European over the degraded inhabitants of Asia; such is the impression produced by resolution, energy, and unwavering courage of a superior race.’6 This kind of attitude allowed Przhevalsky — as well as many of his contemporaries — to combine scientific study with a spirit of military conquest. Petr Semënov Tian-Shanskii, president of the Russian Geographic Society (RGS) and one of Przhevalsky’s greatest patrons, indicated that ‘scientific material is necessary for the definitive conquest of these [Inner Asian] lands for culture and civilization.’7 Like Przhevalsky, the RGS saw science and politics as interrelated. Founded in 1845 by Emperor Nicholas I, it was an association of geographers, zoologists, and ethnographers; technically independent of the government, the RGS received a direct annual grant from the Emperor and published a monthly journal along with numerous monographs by the explorers it supported. In actuality, though, the Society often worked closely with the government, as some of its members were high-ranking officials. Przhevalsky’s missions, for instance, were both planned out and financed through the collaboration of the RGS with the Ministry of War.

It was the RGS which gave Przhevalsky his first break, sending the young officer to survey lands along the Amur and Usuri rivers — territory ceded by China in 1858 and 1860. When he returned in 1869, Przhevalsky immediately proposed a new trip, this time to Mongolia. The explorer’s itinerary reflected his preoccupation with international politics. Przhevalsky undertook to evaluate the Tungan uprising on the Western fringes of the Chinese empire. Persian or Arab peoples who accompanied the Mongols across Central Asia, by the 19th century the Tungans had become fully Chinese in language and dress. They had remained Muslim, though, and initiated a rebellion against the Chinese authorities in 1864. Since the Tungan revolt had drawn in many Turkic and Mongol peoples on the boundary of Russia and China, it became a strategic matter for the Russian state, threatening instability among the Russian empire’s own Muslim peoples. Furthermore, it was a sign of weakness on the part of the Chinese. The presence of such a large-scale uprising suggested to many warhawks in the Russian government that the time was ripe for an all-out invasion of China. Peking had already been compelled to yield Amur and Usuri, and cabinet members like Minister of War Dmitrii Miliutin were convinced that a weak China could be pressured into still further concessions. The RGS, too, acknowledged the political importance of Przhevalsky’s new mission. In addition to mapping terrain and evaluating flora and fauna, the explorer’s task was ‘to throw some light on the current events in the center of China.’8

Przhevalsky returned to St. Petersburg in 1873. He had come to share Miliutin’s aggressive attitude towards China, even suggesting trying to expand the Tungan insurrection by fomenting revolt among Buddhists on the fringes of Tibet. However, the explorer had no taste for the stuffy and formal air of the capital; within two years he was off on another strategic mission in Mongolia. This time, he was to speak with one Yakub Beg, a leader of the rebels in Kashgaria (Eastern Turkestan). The Ministry of War saw in this tribal chieftain an opportunity to wrest yet more land from the Chinese. Przhevalsky was instructed to evaluate Yakub Beg’s political utility and establish a precedent for Russian visitors to the region. As the RGS council wrote in approving the mission, he would ‘teach the Chinese authorities and population to have relations with foreigners and thus open up the path for trade and industrial ventures.’9 Once again Przhevalsky had taken advantage of a political crisis to finance an expedition of exploration. This time, though, he would also learn that political considerations could constrain his movements. The explorer had initially proposed visiting Kashgaria on his way to British India; acting cautiously, the RGS and the Ministry of War vetoed this politically provocative expedition and instructed Przhevalsky not to venture too far from Russian territory.

Przhevalsky’s desire to get to India was not a private whim. The 1870s and 1880s marked the heyday of the so-called Great Game, a race for Asian territory and influence between Russia and Great Britain. The two sides felt compelled to match each other’s achievements: when a Russian delegation reached the Afghan capital of Kabul in 1878, the British immediately dispatched a consulate of their own, only to see it massacred by Afghan tribes. The same principle of competition applied to Tibet. No European had ever visited Lhasa, the seat of the Dalai Lama; by 1880, both Russia and England were undertaking missions specifically destined for the spiritual leader’s court. Indeed, as soon Przhevalsky had returned from his tête-à-tête with Yakub Beg, he proposed his own expedition to Tibet. Once again, he barely bothered to camouflage his political motivations to the general public. In his proposal for the journey, Przhevalsky told the RGS that ‘scientific research will mask the political aims of the expedition and ward off the interference of our adversaries.’10 These words echoed those of Major Kurpatkin, head of the Asiatic section of the army’s Main Staff and Przhevalsky’s direct superior. ‘Along with scientific aims, it is suggested that, as much as may be possible, the expedition also gather intelligence on the political situation in Tibet,’ Kuropatkin told the Emperor in a private memorandum; ‘such an effort …may open the way to our influence over all of Inner Asia, right through to the Himalayas.’11 Przhevalsky himself emphasized the Dalai Lama’s (exaggerated) role as head of 250 million Asian Buddhists and portrayed Lhasa as an Asian Rome. The goal of reaching Tibet would remain with Przhevalsky for the rest of his life. Though suffering from ill health, the explorer proposed a final (and, as it turned out, fatal) expedition to Lhasa in 1888 in order to ‘gather details about the activities of the English in Sikkim regarding Tibet.’12

Despite these efforts Przhevalsky proved unable to reach Lhasa. If politics dictated the direction and focus of his expeditions, they also determined where and when he was able to go. For each of his voyages, Przhevalsky had to obtain passports from the Chinese. The Chinese court was understandably apprehensive about the activities of a Russian general in its mutinous provinces; only the diplomatic acumen of Russian officials in Peking secured for Przhevalsky the necessary documents, and by 1878 the Russian attaché warned the explorer that the Chinese ‘were less to be relied on than ever.’13 Even when the Chinese could be cajoled into providing official passports, the Russian government sometimes chose not to antagonize Peking and curtailed its own explorations. In March of 1878, for instance, Przhevalsky was ordered to halt his march on Tibet and return to St. Petersburg until the political crisis with China – over ownership of the Inner Asian Ili Valley – had abated. Political difficulties could occur on a regional as well as an international level. Throughout his travels, Przhevalsky was often detained by local rulers, some of whom had no doubt been instructed by their superiors to prevent the explorer’s progress. As one provincial governor told Przhevalsky, ‘I shan’t let you [explore]; I have instructions from Peking to see you out of here as fast as possible.’14

As much as he could, Przhevalsky relied on his military power to get around such restrictions. The explorer did not travel with a large entourage for his time; his first two parties comprised only ten men apiece, while his third was made up of fifteen. This group included Przhevalsky himself, two protégé officers, and several Cossacks; they were accompanied by horses, camels, dogs, and the occasional local guide or interpreter. However, all members of the party were heavily armed. During Przhevalsky’s 1880 voyage to Tibet, each of his companions carried a Berdan carbine, two Smith and Wesson revolvers, a bayonet, and forty rounds of ammunition.15 For Przhevalsky, these arms were ‘our guarantee of safety in the depths of the Asiatic deserts, the best of all Chinese passports.’

While Russian arms could get around many roadblocks, local rulers could make travel extremely difficult for Przhevalsky. Oftentimes regional chieftains would let him pass only on the condition that they accompany him themselves, an arrangement that infuriated the explorer. Other Chinese officials would prohibit the local populace from speaking or trading with him, leaving Przhevalsky in dire need of even the most basic supplies. In 1872, for instance, Przhevalsky found himself stranded in the Mongolian town of Ala-Shan when its ruler refused to let him leave and resorted to numerous tricks to detain him. First, the prince claimed to be sick and remained in his tent; when he could no longer keep up this charade, he circulated stories of bandit gangs roaming the countryside and forced Przhevalsky to stay. Such chicanery infuriated the explorer and by the end of the enforced stay he saw the prince as an enemy rather than a friend.

Such bad experiences strained Przhevalsky’s relationship with the Chinese authorities, whom he considered ultimately responsible for the delays. They also hardened Przhevalsky to the local population. In his last book, Ot Kyakhty, the explorer maintains that he was kind to the locals at first, before their unending trickery and stupidity soon drove him to cruelty. ‘Only the experience of later expeditions convinced me that three things are necessary for the success of long and dangerous journeys in Central Asia – money, a gun, and a whip,’ Przhevalsky explains.16 By the 1880s the explorer had become so condescending towards the locals that he prefaced Ot Kyakhty with a warning to the reader, justifying his treatment of them: ‘first of all I should mention that the local population will never understand the scientific goal of our expedition and will regard us with suspicion at best – and hatred at worst.’17

It is hardly surprising that Przhevalsky came to see all Inner Asian peoples as a nuisance and a distraction: after all, he was constantly forced to deal with deceitful and prevaricating chiefs like the prince of Ala-Shan. At times even the stubborn explorer had to succumb to local resistance. Przhevalsky’s greatest loss of face came in Tibet in 1880. As he marched towards Lhasa, local officials became increasingly anxious about a foreigner’s presence in their region; in the end they confronted Przhevalsky with a formal certificate threatening war if he refused to turn back. Faced at last with an impossible military situation, the explorer acquiesced and returned to St. Petersburg.

Obsessed as he was with military and strategic matters, Przhevalsky never abandoned the spirit of ‘scientific exploration.’ His party always carried a large herbarium; on his 1880 Tibetan expedition alone, Przhevalsky brought back some 897 species of plants.18 The explorer’s published travel accounts reflect this dedication to scientific research. On reaching a new area, Przhevalsky invariably begins with a general description of the landscape, pointing out distinctive features like mountains or deserts. He then proceeds to list all the flora and fauna present in the region; for the Taklamakan oasis of Hami, for instance, Przhevalsky names 37 species of flowering plants and 32 species of birds.19 If he stayed in one area for a considerable length of time, the explorer includes general comments on the climate, providing the daily high and lows as well as the number of rainy days.20 For all his condescension towards the locals, Przhevalsky even includes fairly extensive descriptions of their physical appearance, customs, and dress.

When he was not on expedition, Przhevalsky was actively involved in the decision-making process at the Ministry of War. He sat on a number of committees discussing grand strategy in Inner Asia, and, following every journey, submitted a detailed report to Miliutin or his successor, Petr Vannovskii. While these reports were classified and remain unpublished, Przhevalsky made no secret of his opinions, lecturing and publishing widely. His experiences bred in the explorer a contempt for the Chinese as a whole and for their army in particular. Convinced that a war with China would come sooner or later, Przhevalsky took notes on the terrain he explored and even included some of this information in his published expedition reports. While in Hami, for instance, the explorer calculated the city’s strategic value and deemed it ‘of military and economic importance,’ since it could cut off Chinese troops in the Western provinces from the rest of the country.21

Confident of victory, Przhevalsky repeatedly pushed the Ministry of War towards war. He expressed his opinions in a secret memorandum to the Ministry that was later adapted to a chapter in his final book – ‘An Essay on the Current Situation in Central Asia.’ This chapter is so militarist and chauvinistic that it was omitted from Soviet editions of Ot Kyakhty; not surprisingly, the Soviets tried to depict Przhevalsky as a friend of all future Soviet peoples, a tolerant explorer who had nothing but respect for the cultures he encountered. In actuality, the essay advocates open conflict with China on the justification of racial superiority.

Fortunately for Russia, and perhaps for Przhevalsky himself, both the Ministry of War and the Emperor were too cautious and diplomatic to take his warmongering advice seriously. The government’s skeptical attitude intensified considerably following the assassination of Alexander II in 1880. The new Minister of War Vannovskii was far more conservative than his predecessor Miliutin and ended up negotiating with China over the lands it had ceded. Meanwhile, new Emperor Alexander III did not share Przhevalsky’s grandiose vision of empire and told him, ‘I have my doubts about the benefits of such an annexation’ when the explorer proposed taking over Inner Asia.22 Przhevalsky’s opinions made a deep impression on Alexander III’s son, though; the young Tsarevich, future Nicholas II, closely followed the explorer’s reports and personally provided funds for some of his expeditions. Przhevalsky’s influence may well have inspired Nicholas to pursue an aggressive policy in Asia and may even have been a driving force for the disastrous Russo-Japanese war of 1905. The British were similarly mindful of Przhevalsky’s example. Despite a total lack of evidence, they had grown convinced that the Russian explorer had made his way to Lhasa and was now directing the Dalai Lama; to combat this injurious influence, they allowed Francis Younghusband to disregard conventional standards of legality and ‘shoot his way’ to the Tibetan capital.23

Unlike such Western explorers of Central Asia as Stein and Hedin, Nikolai Przhevalsky saw himself as a servant of the state rather than an individual traveler. As we have seen, all of his expeditions were undertaken with a political aim in mind; while he was a dedicated geographer and biologist, he chose his destinations primarily for the sake of military reconnaissance. It is hardly coincidental that Turkestan, Mongolia, and Northern Tibet – the three areas in which the explorer made his greatest discoveries – were all strategically important to the Russian state. Nor was Przhevalsky drawn by the lure of artifacts and paintings, visiting the Thousand Buddha Caves at Dunhuang but passing them over as irrelevant to his mission. Political considerations largely directed his travels and fully consumed his time in St. Petersburg. At the same time, they proved a constant nuisance in his travels, forcing the explorer to stop less than 100 miles from his goal of Lhasa.24 Not surprisingly, politics also turned into a private obsession for Przhevalsky, becoming increasingly prominent in his later travel reports. The explorer came to be obsessed with the need for war, fomenting his reputation as a ruthless conquistador. Fittingly, the statue that now commemorates him in the center of St. Petersburg shows Przhevalsky in full military regalia (see above), as if headed for a posthumous battle.

Notes

1. This is in fact the subtitle to Nikolai Karatev’s 1948 biography of Przhevalsky. Nikolai Karataev, Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalskii: Perviy Issledovatel’ Prirody Tsentral’noi Azii [Przhevalsky: The First Naturalist of Central Asia]. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR, 1948.

2. Unfortunately, the majority of Przhevalsky’s political writings were never released to the public and are this day confined to Russian archives; since I am unable to read them first-hand, I have been forced to quote many classified letters from secondary sources.

3. Archival letter to General Tikhmenev, quoted in Nikolai Dubrovin, Przheval’skii (St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1890), 161.

4. Ibid. Przhevalsky had no plans for a removal of Inner Asian natives; his term ‘bearing away’ implies domination over them if not outright annihilation.

5. Nikolai Przhevalsky, Ot Kyakhty na Istoki Zheltoi Reki: Issledovanie Severnoi Okrainy Tibeta i Put’ Cherez Lob-nor po Basseinu Tarima[From Kyakhta to the Source of the Yellow River: The Exploration of the Northern Boundary of Tibet and the Way over Lob-Nor along the banks of the Tarim]. St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1888, 508.

6. Nikolai Przhevalsky, Mongolia i stana Tangutov [Mongolia and the Country of the Tanguts], (St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1875), II:100. This passage refers to an 1872 battle against a small force of Tangut villagers.

7. ‘Zhurnal torzhestvennogo sobraniia Imperatorskogo russkogo geograficheskogo obshchestva’ [‘Journal of the celebratory meeting of the Imperial Russian Geographic Society’], January 29, 1886. Izvestiia IRGO 22 (1886), 184.

8. RGS memorandum, quoted in Dubrovin, Przheval’skii, 94.

9. RGS memorandum, quoted in Donald Rayfield, The Dream of Lhasa: The Life of Nikolay Przhevalsky (1839-88), Explorer of Central Asia(Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1976), 89.

10. Archival report from August 25, 1878, Quoted in Rayfield, 108.

11. Archival letter from November 1878. Quoted in David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Toward the Rising Sun: Russian Ideologies of Empire and the Path to War with Japan. (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2001), 31.

12. Quoted in Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Toward, 32.

13. Memorandum from the Russian attaché in Peking, Kyander, to Przhevalsky, quoted in Rayfield, Dream, 114.

14. Quoted in Rayfield, Dream, 143.

15. Rayfield, Dream, 114.

16. Przhevalsky, Ot Kyakhty, 50.

17. Ibid., 51.

18. Rayfield, Dream, 114.

19. Nikolai Przhevalsky, Iz Zaisana cherez Khami i Tibet i na Verkhov’ia Zheltoi Reki, (St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1883), 70.

20. See e.g. Przhevalsky’s description of Ala-Shan in Mongolia, 72.

21. Przhevalsky, Iz Zaisana, 88.

22. Alexander III’s handwritten note on a telegraph sent to him by Przhevalsky; archival, quoted in Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Toward, 38.

23. Rayfield, Dream, 208.

24 Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Toward, 32.

Bibliography

- Anuchin, Dmitriy. ‘N.M. Przhevalsky.’ In Russkie Vedomosti, # 293, 1888.

- Brower, Daniel. “Imperial Russia and Its Orient: The Renown of Nikolai Przhevalsky.” The Russian Review, 53 (1994): 367-81.

- Dubrovin, Nikolai M. Przheval’skii. St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1890.

- Johnston, Charles. ‘Prjevalski’s Last Journey.’ The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental and Colonial Record, pp. 133-40. Vol. VIII, no. 15 & 16 (July and October, 1894). Woking: The Oriental University Institute.

- Karataev, Nikolai M. Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalskii: Perviy Issledovatel’ Prirody Tsentral’noi Azii [Przhevalsky: The First Explorer of the Nature of Central Asia]. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR, 1948.

- Karintsev, N.A. N.M. Przhevalskii: Zhizn’ i Puteshestviia [Life and Travels]. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe Uchebno-Pedagogicheskoe Izdatel’stvo, 1937.

- Przhevalsky, N.M. Ot Kyakhty na istoki Zheltoi reki: Issledovanie severnoi okrainy Tibeta i put’ cherez Lob-nor po basseinu Tarima [From Kyakhta to the Source of the Yellow River: The Exploration of the Northern Boundary of Tibet and the Way over Lob-Nor along the banks of the Tarim]. St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1888.

- _____. Ot Kyakhty na istoki Zheltoi reki [From Kyakhta to the Source of the Yellow River]. Moscow: Gosizdat, 1948.

- _____. Mongolia i Stana Tangutov [Mongolia and the Country of the Tanguts]. St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1876.

- _____. Iz Zaisana cherez Khami v Tibet i na Verkhov’ia Zheltoi Reki [From Ziasan through Khami to Tibet and the Sources of the Yellow River]. St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1883.

- _____. Puteshestvie v Ussuriiskom Krae [Travels in the Ussuri Region]. St. Petersburg: V.S. Balashev, 1870.

- Rayfield, Donald. The Dream of Lhasa: The Life of Nikolay Przhevalsky (1839-88), Explorer of Central Asia. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1976.

- Rieber, Alfred J. ‘Russian Imperialism: Popular, Emblematic, Ambiguous.’ The Russian Review, 53 (1994): 331-5.

- Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David Hendrik. Toward the Rising Sun: Russian Ideologies of Empire and the Path to War with Japan. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2001.

Kyrill Kunakhovich has recently completed his BA in History at Yale University.

A Study of the Silk Braids on Stein Chinese Scrolls

Yasuhiko Ogawa

All photographs by Rachel Roberts, IDP

The Stein Collection of Dunhuang manuscripts at the British Library includes over 40 Chinese scrolls that have retained their original covers, staves, and braids. They illustrate 8th-10th century Chinese scroll book design. In Japan there are over 2,000 scrolls extant from the same period and emulating the Chinese scrolls in form and presentation, yet few retain their original braids. Therefore the Stein scrolls are central to understanding book design in the medieval Chinese cultural sphere.

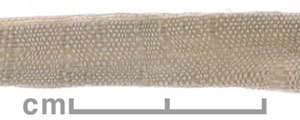

Giles’s catalogue records 35 scrolls, with the exception of Or.8210/S.351, as having a braid.1 However, he only records the colours and materials of some. I have closely investigated each cover, stave and braid based on his list. My newly-obtained data reveal the means of formation for the Chinese scrolls, and challenge current views. Furthermore, the data obtained provides valuable information for the study of Chinese silk textiles. This article is a brief report of the research results.2

Features of the braids

First I will describe the physical features of the braids as textiles. 30 scrolls use pieces of silk cloth, which are folded narrowly and stitched inside (Type A). The other five scrolls use plain-weave silk braids (Type B). The Type A braids are further classified into three types according to their weave structure.

1) Plain weaves (28 braids). The majority of the plain weaves are simple monochrome tabbies. Ten braids are woven with red threads (under present conditions, red, dark red, pale red, pale red-brown or pale brown), five with yellow, four with yellow-green, and four with medium blue. The densities of the yellow-green braids are 46-76 by 24-42 threads/cm [warp by weft], and those of the red braids are 32-72 by 26-44 threads/cm (except one which is unique). They are approximate to those of the silk tabbies (40-69 by 20-39 threads/cm with a few exceptions), found in front of Cave 122 and in Cave 130 at Dunhuang in 1965 and assigned to the mid-Tang period (713-756).3 The warp densities of the medium blue braids (32-44 by 24-32 threads/cm) and the yellow braids (except one) (28-48 by 30-36 threads/cm) are lower. According to Dr Junro Nunome, the warp densities of Chinese plain weave silks reduced in proportion to the weft densities from the ‘Mid-Tang Period’ onwards.4 It is therefore probably that these were woven later than the red and yellow-green braids.

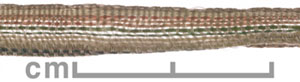

Two plain weaves are polychrome tabbies. These pieces must be different parts of the same cloth dyed dark pink and yellow with undyed areas [Or.8210/S.490(Fig. 1), S.2116]. There seems to be flower-like or spiral-like designs on their faces. Since there is no distinct white space between the pink and yellow areas, particular to clamp-resist dyeing, and the outlines of the designs are vague and clumsy, it is probable that the cloth was painted using a brush.5 In addition, the thread densities of these braids are remarkably low (21-26 by 14-28 threads/cm).

The other plain weaves are unusual. Two pieces of cloth (one is white (undyed) [Or.8210/S.4073](Fig.2) and the other bright pink [Or.8210/S.2794]) are woven with intermittent areas of high density of the warp. Each braid uses the warp as the width, so that a pattern of lateral stripes appears on the faces. The plain weave of another bright pink braid is simple tabby [Or.8210/S.2855]. However, one thick warp thread (0.3–0.35mm) runs through the centre on the outside. Its contrast to the ground (the thread widths are 0.15–0.25mm) seems to be intended as a design.

2) Monochrome twills of the same direction (alternations of 2/1 twill and 1/3 twill) (1 braid [Or.8210/S.3755]). The braid is woven with yellow-green threads. The technique of twills of the same direction appeared in the Tang dynasty,6 and was imported into Japan later than that of twills of different directions, after the mid-8th century.7 It seems to be a new technique.

3) Monochrome qi, a warp-faced tabby with 3/1 twill, on which there is a pattern repeat of units of a lozenge and quatrefoils (1 braid [Or.8210/S.5296]). The braid is woven with green threads.

The five plain-weave silk braids (Type B Fig.3) are identical in their physical features. They must have been manufactured at the same time. And it is likely that they were cut out of one or two long braids. Each braid consists of 24 coloured warp threads, which are arranged symmetrically (3 purple, 3 white, 3 pink, 2 green, 3 yellow, 2 green, 3 pink, 3 white, and 2 purple), and the purple weft. It is not clear why the number of the first purple threads is different from that of the last. The widths are 5-6mm. The weft densities are 16-28 threads/cm.

It should be noted that none of the threads is twisted. Since the cloth-made braids are stitched in twisted silk thread and there is a textile strip woven in Z-ply silk thread in the Victoria and Albert Museum Stein Collection (LOAN:STEIN.402), in future we should address the reason why the braid producers chose untwisted thread.

Book designs at Dunhuang

Are the braids original? All the medium blue cloth-made braids (Type A) and the plain-weave braids (Type B) except one is used for a series of the Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra 大般涅槃經, each volume of which bears the abbreviated name of the Sanjie Temple: 界 on the outside of the cover and the temple seal 三界寺藏經 on the text itself. It is difficult to ascertain any organised arrangement in the order of the braids of two types (see table below).

| Vol. | Pressmark | Short Name | Chapter | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Or.8210/S.4868 | 一界 | 長壽品第四 | B |

| 8 | Or.8210/S.4876 | 一界 | 卷第八 | A |

| 9 | Or.8210/S.93 | 一界 | 卷第九 | A |

| 12 | Or.8210/S.4869 | 二天界 | 聖行品 十二 | B |

| 13 | Or.8210/S.4916 | 二天界 | 聖行品之三 十三 | B |

| 15 | Or.8210/S.4864 | 二天界 | 梵行品第八 十五 | A |

| 16 | Or.8210/S.4861 | 二天界 | 卷第十六 | B |

| 20 | Or.8210/S.2129 | 二天界 | 梵行品之七 | B |

Incidentally, the one medium blue braid not used on a scroll of this text is attached to the Mahāratnakūṭasūtra 大寶積經, 117th volume. Whereas the Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra is recorded in the list of the Sanjie Temple library, 見一切入藏經目録 (manuscript in the National Library of China) by Dao Zhen 道眞 in 934, the Mahāratnakūṭasūtra is not. In another list 三界寺見一切入藏經目録 (Or.8210/S.3624), both the scriptures are recorded. These lists suggests that the Sanjie Temple might have acquired the Mahāratnakūṭasūtra after 934, and it may be presumed that the conservator fixed a Type A braid to the Mahāratnakūṭasūtra, when replacing damaged Type B braids of the Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra with Type A ones. Indeed, Type B is weaker. By contrast, Type A is wide (7–14mm), long (over 520mm) and solid. The readers at the Sanjie Temple must have demanded durability of braids for unfolding and reading scrolls repeatedly.

In the light of this case, a wide and long type of cloth-made braid is likely to have been preferred later. This type is found among red, yellow-green, white, and polychrome cloth-made braids. It is worth noting that two ornamental braids, namely, white and polychrome one, are of this type. They show aesthetic as well as practical interest in book designs at Dunhuang. It is local but unique.8

1. Giles, Lionel. Descriptive Catalogue of the Chinese Manuscripts from Tunhuang in the British Museum. London: The Trustees of the British Museum, 1957.

2. I would like to express my gratitude, first, to Mr Graham Hutt for his advice and help. I am grateful to many scholars, including Ms Helen Persson, Ms Mari Omura, Mr Atsuhiko Ogata and Dr Susan Whitfield. My research is supported by The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation.

3. Dunhuang Wenwu yanjiusuo kaoguzu 敦煌文物研究所考古组.《莫高窟发现的唐代丝织物及其它》.《文物》1972年第12期.

4. Nunome, Junro 布目順郎.『目で見る繊維の考古学』(The Archaeology of Fibre before your Eyes). Tokyo: Senshoku to Seikatsusha, 1992.

5. I owe this presumption to Mr Atsuhiko Ogata.

6. Zhao Feng 赵丰.《丝绸艺术史》(A History of Silk Art). 浙江美术学院出版社出版, 1992.

7. Ogata, Atsuhiko 尾形充彦. 『正倉院の綾』 Shōsōin no aya (The Twill Weave of the Shōsōin Textiles).Tokyo: Shibundō, 2003.

8. I will publish a detailed report later this year.

Yasuhiko Ogawa is Professor at the College of Literature, Aoyama Gakuin University.

NOTE: IDP is currently taking detailed digital shots of the braids on these 35 scrolls and the others and indexing them so that users can search in Advanced Search for ‘Subject’ = ‘braids’ to show the images. All these items will be included in a forthcoming publication by Zhao Feng of the Hangzhou Silk Museum on the Dunhuang textiles.

Textile Exhibition and Publication

Central Asian Textiles and Their Contexts in the Early Middle Ages

(Riggisberger Berichte, vol. 9)

edited by Regula Schorta

with contributions by A. D. H. Bivar, Jorinde Ebert, Richard N. Frye, Han Jinke, Amy Heller, Judith H. Hofenk de Graaff, Li Wenying, Lin Chunmei, Boris I. Marshak, Valentina I. Raspopova, Wilma G. Th. Roelofs, Sabine Schrenk, Angela Sheng, Wu Min, Xu Xinguo, Marianne Yaldiz, Yokohari Kazuko, Zhao Feng.

Paperback, 320 pages, 240 illustrations, 2006, ISBN 3-905014-19-X

CHF 85 + postage

www.abegg-stiftung.ch

ABEGG-STIFTUNG Exhibition

Woven Gold: Metal Threads in Textile Art

30 April – 12 November 2006

Riggisberg, Switzerland

This special exhibition shows textiles with gold and silver thread that have long been admired for their beauty and sophistication. From ancient times until the 18th century, from China to Europe, they have always been the most precious textile artworks of their age. Their shimmer and sheen and diversity of technique still fascinate us today.

For details see: www.abegg-stiftung.ch

The Use of Melinex for Enclosing Manuscript Fragments

Barry Knight

Since the use of Melinex in storing manuscript fragments was last reviewed in 1999 (IDP News 14) there have been continuing questions about whether this material is truly inert and suitable for the purpose. This article aims to present the facts as far as they are known in 2006.

Melinex is a trade name of DuPont Teijin Films for its polyethylene terephthalate (PET) polyester films. Other trade names for PET film are Mylar (also DuPont) and Hostaphan (Mitsubishi). Here the film will be referred to generically as PET.

There are probably four separate issues relating to enclosures for fragile manuscripts or fragments. The first is to do with physical protection: glass provides better protection for very fragile material, but it is very heavy and fragile itself, so it needs special care in handling and storage. A large collection of fragments enclosed in glass would take up a great deal of space, and might be inconvenient for scholars. PET enclosures are much lighter and easier to handle, but may not provide sufficient protection when the fragments are large or particularly brittle. A related issue is that PET is softer than glass and is therefore more easily scratched by grains of sand etc. adhering to the manuscript fragments. This problem was examined by David Jacobs in IDP News 15.

The second issue concerns off-gassing or exudation from the enclosure material as it degrades: this is a serious problem with substances like cellulose acetate or PVC, but not with polyesters. All the evidence is that PET is an extremely stable and inert material, and the information given by Dr Barry Cope in IDP News 14 still stands. Enclosing manuscripts in PET is quite different from heat lamination using PVC, which is indeed a very harmful process.

The third issue relates to off-gassing or exudation from the object itself, and of course this may happen whether the enclosure is glass or PET. This has recently been reviewed by David Jacobs and Joanna Kosek of the British Museum (‘What happens to enclosed paper?’ in Art on Paper: Mounting and Housing, London: Archetype, 2005), but is an area where further research is required.

Finally there is the issue of the environment (temperature and relative humidity) within an enclosure. It is difficult to predict what happens to the environment inside an enclosure with a small volume and a large surface area, and this is strongly influenced by the presence of hygroscopic material such as paper. This too is an area where further research is required, but again, the effects will be largely independent of whether the enclosure is glass or PET.

In summary, there is no new evidence that storage of manuscript fragments in PET enclosures is any more harmful than storing them in glass. Ultimately, it is a matter for the conservator’s professional judgement as to what material is appropriate for an enclosure, taking into account the fragility of the item, the level of use and the method of storage.

Barry Knight is Head of Conservation Research

The British Library

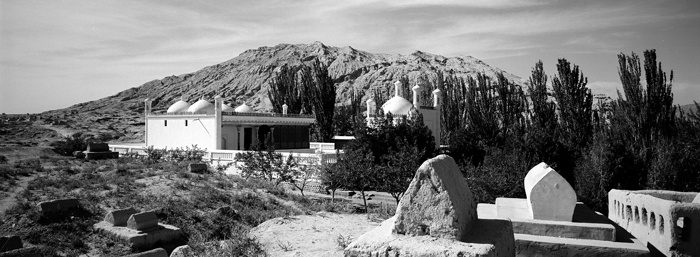

Kashgar: Cultural Monuments and Spaces

This project brings together teams from the Monash Asia Institute (hereafter MAI) from Monash University in Melbourne, Australia and Urumqi Normal University in Urumqi, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China in an international research collaboration to document, measure, and define the most significant cultural monuments and spaces of Kashgar. For the purposes of this project, Kashgar is defined as the modern and ancient city and the eleven counties that currently form the greater region of ‘Kashgar’. MAI and Urumqi Normal University teams are working with the support of the Department of Tourism, Government of Xinjiang and the Department of Foreign Relations, Kashgar.

The project will produce a popular book on Kashgar that provides a photographic essay appealing to a wide readership internationally and within China. The book will be launched at an international conference on Kashgar to be held in either Melbourne or London. This will be organised in collaboration with Sotheby’s and the Asia Society to generate an interest in Kashgar among the larger cultural community. On the publication of the Chinese edition there will be a second launch in Beijing and Urumqi. Each author will then continue to work on Kashgar in their field of speciality with a view to publishing detailed, expert monographs in their area. This work will be supported and coordinated by the MAI in conjunction with the Urumqi Normal University. The MAI also undertakes to work with the local museums, curators and keepers of cultural relics in Xinjiang to ensure that their work receives international recognition.

For further details of the project please contact: Marika Vicziany

Publications

Uygur Patronage in Dunhuang: Regional Art Centres on the Northern Silk Road in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries

Lilla Russell-Smith

Brill’s Inner Asia Library: 14

Brill, Leiden & Boston, 2005

HB, xxviii, 296 pp.

EURO139, USD181

900414241X

To order: www.brill.nl

Bulletin of the Asia Institute: 15

August 2005

This issue contains a number of articles ‘in the news’: an analysis of the authenticity of so-called Jiroft finds—forgeries?; and up-to-date information on two tombs of Sogdian leaders found recently at Xi’an, with unusually clear illustrations of the stone carvings, some of which point to Zoroastrian beliefs. Among other studies discussed are Bactrian and Khotanese texts; Byzantine-Iranian relations; Iranian views of the red jewel called ‘spinel’; Parthian and Hellenistic evidence for a North India cult; Indian architecture; new finds of Sasanian silver bowls; Mongolian deer stones.

USD65 plus shipping.

To order contact: Carol Altman Bromberg

The Clay Sanskrit Library

The Clay Sanskrit Library is the only series of books that, through original text and English translation, gives an international readership access to the beauty and variety of classical Sanskrit literature. The national Indian epics; lyric poetry and novels; drama and satire; the religious narrative works of Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism — in short, the entire classical heritage of Sanskrit literature is now represented in handy and elegant pocket volumes in which an up-to-date original text and literary and accurate English translation face each other page by page. Forty-four leading scholars from nine countries provide illuminating introductions as well as essential critical and explanatory notes. Co-published by NYU Press and the JJC Foundation, nineteen titles have appeared since the 2005 launch. Within the next five years the CSL will grow to a hundred titles.

For a list of titles and to order see: www.claysanskritlibrary.org

The Temples of Lhasa: Tibetan Buddhist Architecture from the 7th to the 21st Centuries

André Alexander

Tibet Heritage Fund

Conservation Inventory: Vol. 1

Serindia, 2006

HB, 336 pp.

USD65

1-932476-20-2

To order: www.serindia.com

Forthcoming

Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology

The Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology is a new journal launched by the Circle of Inner Asian Art, replacing their Newsletter (Issues 1-20, 1995-2005). Uniquely the journal covers the vast regions flanking the ancient Silk Roads from the Iranian world to western China, and from the Russian steppes to north-western India, which today include Iran, Afghanistan, India, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, and areas within the People’s Republic of China, namely, Gansu province, Inner Mongolia, and the Xinjiang-Uyghur and Tibet Autonomous Regions. The Circle has been especially interested in the research of cultural interchange between these regions. The journal’s main focus will be on the pre-Islamic and early Islamic period art and archaeology of Inner Asia. Related scholarly articles on language and history will also be published.

Edited by Dr. Lilla Russell-Smith (London) and Dr. Judith A. Lerner (New York)

Print version only: EURO50 + shipping

Print and online verion: EURO55 + shipping

To order: www.brepols.net

Steppe Magazine

Late September 2006 sees the publication of Central Asia’s first glossy magazine devoted to the arts, culture, history, landscape and people of Central Asia (focusing on the five post-Soviet Central Asian states, Afghanistan and western China). By using both local and foreign scholars, journalists, writers and photographers, Steppe will celebrate the best features of the region. Steppe will look at art and culture in their widest sense to include architecture, archaeology, objects, interiors, textiles, people, landscape, history, music, cooking and more. In addition, Steppe will publish up to date information on cultural events in the region, plus reviews of books, films and international exhibitions highlighting Central Asia. Steppe will be produced in the UK and issued twice a year.

To find out more and to subscribe go to: www.steppemagazine.com

Travel Award

The Royal Society for Asian Affairs (RSAA), UK, invites applications from individuals aged 18-25 for an award established in memory of Sir Peter Holmes MC (1932-2002), a long-standing member of the society who, besides becoming Chairman of the Royal Dutch Shell Group, was a distinguished traveller, mountaineer, fisherman and photographer.

The aim of the award is to encourage purposeful travel in Asia by young people. Applicants should submit a plan of a project involving travel in a country or countries of Asia and relating to the history, geography, politics, environmental conservation, culture or art of the place to be visited. Any part of Asia, including the Middle East, may be chosen. Plans should be costed as far as possible and should state the duration of travel involved and how the costs will be met. The award will be made on the basis of orginality, coherence, evidence of background knowledge, and the degree to which the project is likely to add to general understanding of the area chosen and/or to benefit local people or the applicant. Preference will be given to projects that are not requirements in an academic or other course.

This notice refers to travel in 2007. The award will consist of up to £1000 and two years’ free membership of the RSAA. The adjudicators have discretion to divide the award among more than one candidate if appropriate. the successful candidate will be notified by 31 January 2007.

Applications should be sent by 31 October, 2006, to:

The Secretary, RSAA

2 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8PJ, UK

email: [email protected]

Digitisation, Cataloguing & Research

Database entries as of end June 2006

| ITEMS | IMAGES | |

|---|---|---|

| UK | 53,046 | 85,831 |

| CHINA | 9,160 | 11,641 |

| RUSSIA | 516 | 2,958 |

| JAPAN | 16 | 16 |

| GERMANY | 4,296 | 5,368 |

Leverhulme Research Project

This three-year project to carry out a palaeographical and codicological study of the Chinese and Tibetan manuscripts from Dunhuang started in 2005. Initial work involves collecting data on as large and representative a group of manuscripts as possible, including paper size, laid and chain lines, format of the manuscripts, attachments etc. At the same time a digital database of the individual characters (for Chinese) and syllables (for Tibetan) is being compiled. Software has now been developed by IDP to collect this data and incorporate it into the existing IDP database structure. Tens of thousands of characters and syllables have already been ‘cut out’ in this way.

The project researchers — Susan Whitfield, Sam van Schaik and Imre Galambos — all attended the University of London Summer School in Palaeography held at the Centre for Manuscript Studies in June 2006. Imre Galambos has held discussions with Nanjing University about collaboration. The next six months will see further data collection, the preparation of a glossary or terms in Chinese/English and preparation of web pages on palaeography and codicology.

Dr Imre Galambos’s previous research, on the orthography of early Chinese writing, has recently been published (see right). Contact IDP for details.

Ford Foundation Project

Despite the rich tradition of Chinese, Tibetan, Indian and Central Asian studies in China, India and Russia, most scholars from these three countries have few opportunities to meet or work together on joint projects. This two-year project, funded by the Ford Foundation, started earlier this year and aims to facilitate such exchanges on three research projects. Alastair Morrison of IDP UK is Project Coordinator and he is joined by local Research Coordinators in each centre.

The first symposium will be hosted by the National Library of China in autumn 2006 (tbc) and will cover the topic of The Sutra of Golden Light (Suvarnaprabhāsottamasūtra); its transmissions; translators; different versions; as well as its visual representations in Central Asia. A web resource resulting from this will be live at the end of this year.

Sanskrit Cataloguing

An international team of scholars led by Professor Seishi Karashima at the International Research Institute of Advanced Buddhology (IRIAB) at Soka University, Japan, have started work on cataloguing the Sanskrit fragments at the British Library.

Almost 1500 fragments have now been digitised and given to the team: they will start coming online on IDP in October this year. The research and catalogues will be published online on IDP and in a new journal, the first issue of which is due out shortly. Full details will be given in the next issue of IDP News.

Map Interface

Thanks to The Pidem Fund, work is now scheduled for completion of the first stage of the IDP map interface for later this year. Full details will be given in the next issue of IDP News.

Translations

IDP receives numerous requests from non-specialists interested in knowing more about the manuscripts from the Silk Road yet unable to read them in the original languages. Scholars of one area are also often unaware of relevant material in another language. For this reason, we are starting to collate translations of key texts which we will make accessible on the web linked to the relevant manuscripts. Where possible, we are using existing translations.

Several scholars and their publishers have already generously agreed to make their translations available for IDP. These will be online by the autumn.

If you have a translation of a text please consider letting us use it on the IDP site. You will be fully credited and retain copyright. Please contact IDP for further details.

IDP Worldwide News

IDP China

Apart from ongoing digitisation, staff at IDP China have recently completed a translation into Chinese of Roderick Whitfield’s catalogue The Art of Central Asia: the Stein Collection in the British Museum. This is online on the British Museum website and is currently being converted by staff into XML for mounting on IDP. Work will then start on keying in and conversion of Chinese catalogues of the material in the National Library of China (NLC).

Following the report in the last newsletter, IDP China is now ready to expand. Two new camera set-ups (a scanning back and a single shot-back) will be shipped to Beijing in the autumn and new staff employed to operate them. An IDP training team will spend at least one week in Beijing and a schedule of work will be agreed to include continuing work on the Chinese scrolls and fragments from Dunhuang, along with other material.

In June, the NLC mounted an exhibition of Chinese ancient books and their conservation. The exhibition showed the history of Chinese book conservation, and how modern China has purchased, stored and conserved ancient books. Twenty-five Dunhuang manuscripts were on display.

On 29 June, dignitaries from publishing, library and scholarly circles attended a symposium at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on the publication of the Dunhuang documents at the NLC. The publication was highly praised for being the most complete surrogate form to date of the Dunhuang collections at the NLC, helping to resolve the contradiction of protecting the manuscripts while allowing scholars access.

The NLC IDP website is now almost completely translated into Chinese, along with a newly written page on the Chinese expeditions, archaeology and collections. The database searches will be fully implemented into Chinese shortly.

The NLC will host the first Ford Foundation Project symposium in November this year. Gao Wa, who is fluent in Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan and Japanese has been appointed as Research Coordinator on this project.

IDP Russia

Digitisation is continuing apace at the Institute of Oriental Studies in St Petersburg. Svetlana Shevelchinskaya has already prepared almost 3000 images and Oleg Kenunen is now working with her on the manipulation and preparation of images for the database. The basic entries for the scrolls are now completed and work should soon be finished on the entries for the fragments. After this Menshikov’s catalogue — in Russian and Chinese — will be keyed in and marked up using XML for importing into the IDP database.

Katerina Karmanova, who is studying for a PhD on the history of the collections at the Institute of Oriental Studies has been appointed as Research Coordinator for the Ford Foundation Project.

IDP Japan

Work has now started on inputting data on the manuscripts in the Omiya Library of Ryukoku University and the data on existing digital images is being linked to this. Please watch the web site for more images coming online over the coming months.

IDP Germany

Under the title ‘Literärische Stoffe und ihre Gestaltung in mitteliranischer Zeit’ the Akademienvorhaben Turfanforschung of the Berlin Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities organized a colloquium on the occasion of the seventieth birthday of Prof Dr Werner Sundermann, the well known specialist in Iranian and Manichaean studies. This colloquium, which took place on March 30–31, 2006, was generously sponsored by the Fritz Thyssen Stiftung für Wissenschaftsförderung. Papers were given by colleagues of W. Sundermann from all over the world, among them M. Macuch, M. Hutter, Ph. Gignoux, N. Sims-Williams, Y. Yoshida, Sh. Shaked, A. Hintze, F. Vahman, E. Jeremias, M. Maggi, F. De Blois, P. O. Skjærvø, E. Morano as well as students and colleagues in Berlin. The papers will be published in a conference volume in near future.

Berliner Turfantexte XXIV (Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, Belgium) will be appearing shortly. Devoted to the ‘Hymns to the Living Soul’ and edited by D. Durkin-Meisterernst, it presents editions of Middle Persian and Parthian Manichaean texts in the Berlin collection. The texts were used by the Manichaean community to accompany the task of releasing the living light imprisoned in the material world.

Other Collaborations

New Delhi, India

Discussions were held in June with the National Museum of India regarding collaboration with IDP to digitise the museum’s collection of central Asian paintings and antiquities. The NMI’s sister institution, the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts will also collaborate in this work, and one of their researchers will be appointed as Indian research coordinator for the Ford Foundation research project. Scholarly exchange and training were also discussed.

Dunhuang, China

Discussions were held in April with the Dunhuang Academy (DHA) regarding collaboration with IDP to digitise their collection of Dunhuang manuscripts. The training of DHA staff is planned for the autumn at the NLC, Beijing; equipment will then be set up at DHA. Once the project begins, DHA will act as coordinator for including other Dunhuang collections in Gansu province on the IDP database.

IDP UK: A New Team

Over the past six months IDP has restructured and employed new staff to cope with its increased and changing workload. Sam van Schaik and Imre Galambos have moved to work primarily on the Leverhulme Research Project, with Sam also in charge of XML and Imre with a watching brief on IDP Japan. Marta Matko is working with Sam on the Tibetan manuscripts. Alastair Morrison is now Overseas Project Coordinator responsible for the Ford Foundation project. We welcome Barbara Borghese as the UK and European Project Coordinator. Existing studio staff have taken on additional responsibilities, reflecting the wide remit of IDP’s activities. Abby Baker becomes Training Coordinator and Digitiser, Rachel Roberts is Picture Editor and Digitiser, and Vic Swift is now Web Master, Designer and Digitiser. Alastair and Abby will be responsible for overseeing educational activities. Kate Hampson continues as Administrative Manager although also taking on more responsibility for web content. We also welcome Sarah Biggs as Communications and Promotions Officer. helping Susan Whitfield promote IDP and raise core funds for the coming years.

IDP’s Online Interactive Silk Road Quest

Silk Road Quest is an educational interactive web game for eleven year-olds upwards devised by IDP but yet to be implemented on the web. We are therefore asking for your financial support to make this possible. We cannot do this without you. Every GB£ contribution you make will help us travel one kilometre along the Quest’s route and bring us closer to making this resource accessible to children the world over.

Help young people embark on a virtual journey from Samarkand to Chang’an

This digital version of IDP News is based on the print version of the newsletter and some links and content may be out of date.

This issue, No. 27, was published Spring 2006.

Editor: Susan Whitfield

Designer: Vic Swift

Picture Editor: Rachel Roberts

ISSN 1354-5914

All text and images copyright their creators or IDP, except where noted. For further information on IDP copyright and fair use, please visit our Copyright page.

For further information about IDP please contact us at [email protected] or visit our Contact page.