Following the Tracks of a Tenth-Century Buddhist Pilgrim

Imre Galambos and Sam van Schaik

Photographs by Imre Galambos

For the past four years, Sam van Schaik and Imre Galambos of IDP have been working together on a book about a pilgrim’s letters of passage. The manuscript (IOL Tib J 754 in the British Library) originally belonged to a Chinese Buddhist monk who passed through the Hexi Corridor in the tenth century on a pilgrimage from China to India. The letters are written in Tibetan, with the pilgrim’s own Chinese notes scribbled in between. These letters are just one part of the manuscript which is a fascinating composite of material acquired in the course of a pilgrimage. As our book on the manuscript was nearing completion, we wanted to see first hand the Buddhist sites along the pilgrim’s route. Our objective was to travel to these sites to locate additional information that could be used to complement our work on the manuscript. Thanks to the generous support of the British Academy, we were able to make this trip in the early summer of 2010.1

According to the letters of passage, the Chinese monk set off on a pilgrimage from Wutai Shan with the ultimate goal of studying at the great monastery of Nālandā in Northern India. However, the only part of his journey detailed in the manuscript was the area around the Hexi Corridor (in the modern provinces of Gansu and Qinghai). During the tenth century this region was dominated by small Tibetan kingdoms. There is still a strong Tibetan presence in the region, which is known as Amdo in Tibetan. According to the manuscript, the pilgrim was travelling this way in the year 968, passing through Hezhou, Tsongka, Liangzhou, Ganzhou and then to Dunhuang. He may well have been associated with a large group of pilgrims who, according to the historical records of the Song dynasty (960–1272), left China in 966 with the blessings of the emperor.

The manuscript itself ended up in the Dunhuang cave library, where it remained for nine centuries before being brought to England by the archaeologist and explorer Aurel Stein. We do not know what happened to the pilgrim before and after the part of his journey detailed in the manuscript, or indeed whether he ever reached India. Yet the geographical proximity of the sites mentioned in the manuscript suggested that they were consecutive stations along a pilgrimage route, in which case it would be useful to visit them each in turn, following the original pilgrimage route as closely as possible. In this way we hoped to be able to establish whether the route we had reconstructed from the manuscript really was feasible, and complementing the information that we had thus far derived from the manuscript with field data.

We arrived in Lanzhou, the provincial capital of Gansu, on 27th May, just in time to avoid the heat of full summer. The next morning we set off towards Linxia, which is a few hours drive to the southwest of Lanzhou. This is the site of the old town of Hezhou that lay along one of the main pilgrimage routes to the west. It also features in our manuscript as the first stage in our pilgrim’s trip through the Hexi corridor. From Linxia, we travelled through spectacular scenery along the steep gorges that rise up along the Yellow River towards Xunhua, the seat of a county by the same name. This region is inhabited by the Salar, a Turkic people who came here from Central Asia and, like the Hui, follow Islam. Unlike Linxia, there is still a strong Tibetan presence in Xunhua. Our objective was to visit an old Tibetan Buddhist site called Dantig, one of the places where our pilgrim stayed. In fact, our manuscript represents the earliest occurrence of the name of this site. According to modern maps, Dantig is very close to Xunhua, only about three or four miles as the crow flies, across the Yellow River and into the mountains. Because of this, we decided to hike there directly from Xunhua instead of going the recommended way, involving a lengthy detour by car and approaching the monastery from the north.2

Hiking across the mountains, as we soon found out, was a much more strenuous route involving five hours of continuous climbing up the steep mountainside. The path was marked by small cairns at every point where the way became uncertain. These cairns indicated that this was still a significant pilgrimage route for local Tibetans. The presence of Tibetans became more apparent as soon as we left the Yellow River valley and began to climb; conversely few of the local Salar or Hui lived above the valley. Thus the population groups are distinguished by altitude, a kind of ‘vertical stratigraphy’. We met nobody on the path except for two Tibetan goatherds working on different sides of the mountain.

The path rose steeply up the mountainside and along a ridge, with sometimes dizzying drops to the valley floor some 500 metres below. At certain points the path, cut into the mountainside, had almost crumbled away. On the ascent we passed a place of offering to a Tibetan mountain deity, a massive cairn impaled with arrows up to 5 m in length, bearing flags which fluttered in the strong wind. Around it the ground was covered with small printed textile squares, known as ‘wind-horses’ (rlung-rta) in Tibetan, which are cast into the wind during rituals. Eventually, the climb levelled out and then we descended into the green slopes of another valley.3

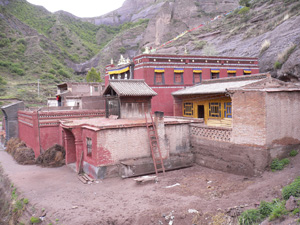

Dantig is a completely secluded place, lying at a high altitude in a small valley. Residential buildings lie at the bottom of the valley, while most of the temple structures are on the mountain slopes around it. Usually, there are about seventy monks in residence but when we arrived most of them were away on leave and in the entire valley there were only four or five people. Talking to them and asking questions was not easy, since none of the present monks understood Chinese and spoke Tibetan only in the Amdo dialect. We stayed at Dantig for the night, sleeping on a kang, a kitchen with a raised platform that served as an eating area and bed, heated from underneath by the cooking fire. At night the room was visited by what sounded like dozens of rats. In the morning, we continued to explore the valley. A trail along the valley side leads to several cave temples, including the cave where the famous monk Gewa Rabsel is said to have lived. According to the Tibetan historical traditions, Dantig was the primary seat of Gewa Rabsel, who is said to have ensured that the order of monks did not die out in Tibet in the chaotic period after the fall of the Tibetan empire. Travellers from Central Tibet were ordained here, before bringing the monastic ordination back to Central Tibet in the late tenth century. The site is also associated with a number of other famous lamas who taught and meditated here, including two of the Dalai Lamas.

Towards the head of the valley, near one of the larger temples, we noticed the remains of rock paintings. These paintings are apparently early, perhaps dating to the ninth or tenth century; later consultation with art historians confirmed this impression. The paintings include large standing figures of Śākyamuni and Maitreya, in a similar style to those seen in Western Tibet. Around these are multiple images of Buddhas and a flying female figure similar to those seen in cave temples at sites like Dunhuang. When the time came for us to leave the valley, we discovered that this was not a trivial matter. We had originally planned to walk north towards the first village with a road but were told that we would not necessarily have access to a vehicle there. There was only one car in the village and it might have already left by the time we arrived on foot. So we had no choice but to walk back through the mountains the way we had come. Going downhill was significantly easier, and we were able to enjoy the breathtaking views once again, but it still took us over four hours to descend to the Yellow River and the town of Xunhua.

Having visited Dantig, we moved northeast in order to explore the region of Tsongka, the next stop on our tenth-century pilgrim’s route. Tsongka appears in one of the earliest Tibetan inscriptions, the Zhol pillar in Lhasa (from the 750s or 760s), as a region contested by the Tibetan and Chinese armies. Later, at the beginning of the eleventh century, Tsongka came to the aid of China’s Song dynasty, as one of the last bastions holding out against the rising Tangut empire. Since Tsongka was friendly with the Chinese, it became the Song dynasty’s lifeline in maintaining the trade route westwards. Tsongka continued as an independent kingdom until the twelfth century when it was finally swallowed up by the Tangut empire.4

According to the pilgrim’s itinerary, he was keen to see the ‘gold and turquoise temples’ of Tsongka. We stayed for the night in Xining, a busy city and the seat of the Qinghai Provincial Government. From there we took a trip to the Kumbum Monastery (Ta’ersi in Chinese), which currently serves as an important pilgrimage site and, at the same time, a major tourist attraction. Although the monastery was only founded in the late sixteenth century, far too new to have been visited by our pilgrim, it may well represent the site of previous Buddhist establishments. It was also interesting to note that its architecture incorporates turquoise wall tiles and gilded roofs.

The ancient site of Tsongka itself is probably closer to the modern town of Ping’an, not far from Xining Airport. The most important early Buddhist temple in this region is Martsang (known as Baima si, or ‘White Horse Monastery’ in Chinese), located in the red rock mountains that rise up to the north of the city. In traditional Tibetan histories this cliffside temple was the adopted home of three refugee monks who fled Tibet after the fall of the Tibetan empire. These three are said to have passed on the monastic ordination to Gewa Rabsel, who settled in Dantig. The temple at Martsang is attached directly to the mountainside, and is accessible through a series of narrow stairs and ladders. Fenced away from the public but still visible in the distance are remains of caves carved into the red cliffs. At least one of these has a mural on its ceiling in the form of three maṇḍalas. Also visible are square apertures in the cliff side, which were probably used to anchor wooden structures like stairs and walkways.

The next site on the pilgrim’s route would have been Liangzhou in the area of modern Wuwei. Travelling from Tsongka towards Liangzhou would require days of trekking in the high mountain range that rises up to the north of Tsongka. A more circuitous, but less strenuous route, would follow the direction of the modern road back east towards Lanzhou before turning north to Liangzhou. In our case, we had come to the end of our time in Gansu and Qinghai, and had no choice but to leave the exploration of that part of the pilgrimage route for another time.

The trip had allowed us to understand much better the terrain that our pilgrim had negotiated and the main routes along which he must have passed. It became quite clear that his detour away from the more direct route of the Hexi corridor to visit the Tibetan monasteries of Qinghai would have required much hard mountain walking. This in turn suggests that the purpose of the pilgrimage was not merely to get from China to India by the quickest route, but to travel a route that would allow access to as many significant Buddhist sites as possible. We can also infer that the Tibetan monasteries were, in the tenth century, famous enough to attract Chinese Buddhist pilgrims. And in two of these sites, Dantig and Martsang, we were able to confirm that Buddhist art possibly dating back as far as the time of the pilgrim’s journey still remains.

Dr Imre Galambos and Dr Sam van Schaik are both Research Project Managers at IDP UK.

NOTES

1. Sam van Schaik, Imre Galambos. Manuscripts and Travellers: The Sino-Tibetan Documents of a Tenth-Century Buddhist Pilgrim (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2011).

2. Two guides to the local region proved particularly informative: (i) Andreas Gruschke. The Cultural Monuments of Tibet’s Outer Provinces: Amdo (Volume 1. The Qinghai Part of Amdo) (Bangkok: White Lotus, 2001) and (ii) Gyurme Dorje. Tibet (3rd edition) (Bath: Footprint Books, 2004).

3. On the Tibetan cults of mountain deities and the associated rituals, see for example Samten Karmay. The Arrow and the Spindle (Kathmandu: Mandala, 1997), 380–462.

4. On Tsongka in the tenth and eleventh centuries, see Iwasaki Tsutomi. ‘The Tibetan Tribes of Ho-hsi and Buddhism during the Northern Sung Period,’ Acta Asiatica 64 (1993): 17–37.

A Technical Study of Portable Paintings from Cave 17 in US Collections

Matthew Brack and Erin Mysak

Project background

This project began in 2009 as a component of a Craigen W. Bowen fellowship in paper conservation at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museums. Dr. Robert Mowry, head of the Department of Asian Art at the Museums, had selected two examples of early Chinese Buddhist painting on textile originally from the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang, Maitreya’s Paradise and Eleven-Headed Guanyin, for display within the newly refurbished Harvard Art Museums building. As centrepieces for a new exhibition of Harvard’s Asian art collections, they were put forward for detailed examination.

Following early consultation with colleagues at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, the project quickly expanded to include an examination of three more portable paintings on textile from the Mogao Caves, all dating to the tenth century; from the Museum of Fine Arts, Guanyin as Saviour from Perils, and from the Freer Gallery Guanyin of the Water Moon and Ksitigarhbha Bodhisattva, whose pigments had previously been studied in some detail.

Our technical study was the first detailed examination of textiles used in portable paintings from Mogao Cave 17, a key component that differentiates them from the cave murals. It also addresses the manner in which the two aspects of paint and textile have interacted within these objects to produce distinct styles of Buddhist painting in Chinese Central Asia. The project was the first to use radiocarbon dating to confirm the age of a portable painting from the Mogao Caves, confirming the authenticity of Eleven-headed Guanyin.

The significance of the portable paintings and past perspectives

The preservation of material inside Cave 17 resulted in the oldest surviving collection of Chinese Buddhist paintings on textiles anywhere in the world. As such, it is surprising that the portable paintings were yet to be the focus of any significant technical research in their own right. The traditional research priorities surrounding the Mogao Caves and their associated artefacts have been the cave murals themselves and the manuscripts recovered from Cave 17, prized for their historic and philological value; the portable paintings, it would seem, were swept up somewhat arbitrarily with these manuscripts by the early Western visitors to the Caves. This is perhaps best revealed by Paul Pelliot’s journal, which he kept throughout his stay at Mogao during the spring of 1908. His journal entry from 14 May states:

‘Purchased 38 large paintings from the caves from Wang, for 200 taels, and some wood for a small sum. The paintings are interesting, but unfortunately they are all in the ‘usual style’ of the tenth century, the most static and monotonous period at the caves.’1

The limited examination of these paintings since Pelliot’s time has been confined to art historical observation and scattered pigment analysis; they have also been omitted from studies of Dunhuang textiles. This project therefore had significant scope for the exploration of some basic, yet critical themes in the examination of these paintings. Since the paintings are portable, where and how were they made? What can be learned from their textile supports and original mounting systems?

Findings

Pigments: the presence of lapis lazuli

Analysis began with XRF as an indicator of elemental composition.2 This examination was refined through the use of FTIR and Raman spectroscopy, comparing spectra to the Infrared and Raman Users Group (IRUG) Spectral Database, complemented by polarising light microscopy (PLM) and backscattered SEM.

Significantly, lapis lazuli has been found in every one of the five tenth-century paintings examined in this study. This is noteworthy, since the use of lapis lazuli within the cave murals at Mogao became highly restricted or stopped altogether by the end of the Tang dynasty (618–907)3, which raises the question of why this precious pigment would be so prevalent on portable paintings and not the wall murals painted at the same time and location.

It is likely that the use of lapis lazuli may have declined at Dunhuang with the expansion of Muslim Turkic powers into western Central Asia during this period, with the lapis mines at Badakhshan under their sphere of influence. The end of Buddhist artistic practice in these regions highlights the relationship between Dunhuang and the Buddhist oasis of Khotan to its south-west. Sarah Fraser has noted that Khotanese paintings datable to the tenth century were found in Cave 17, which may have been brought there from Khotan following the Muslim Turkic invasion (Khotan eventually fell in AD 1006).4 Given the close relationship between Dunhuang and Khotan, it seems possible that Khotan, half the distance to the source of lapis lazuli in Badakhshan, may have supplied the materials or even the artist workshops that created the Dunhuang portable paintings in this study.

Another explanation for the use of lapis lazuli on portable paintings is that they may simply have been painted for wealthy clients who wanted the very highest quality, and rarest, materials – contemporary mural paintings in the Mogao Caves were created with less valuable pigments due to the caves’ size, which would have required a far greater volume of pigment than the portable works.5 Regardless, the disruption to the lapis lazuli trade limited its use to smaller scale works after the Tang dynasty; the lapis lazuli found in them would have passed through western oases like Khotan to arrive at Dunhuang from Badakhshan. Essentially, the presence of lapis on the portable paintings raises the question of the paintings’ origin and the nature of artistic interaction along the Silk Road, a suggestion reinforced by an examination of the textiles and painting technology associated with them.

Textiles: qualities of silk and the use of bast fibres

A key characteristic observed in the Dunhuang silk paintings examined is the evidence of ‘recycled’ silks, that is: silks that were not woven for the purpose of painting. Guanyin as Saviour from Perils has been painted on a monochrome weave with a damask diamond pattern, a geometric design characteristic of damask on plain weave silks found at Dunhuang.6 The re-use of cloth is in keeping with the Buddhist tradition, where the monk’s kāṣāya robe was constructed from used and discarded fragments.

There are also silks recovered from the Mogao Caves that are of very different quality, with higher thread count and density. While the finest pigment, lapis lazuli, came from the west along the Silk Road, the finest silks came from the east in imperial China. The plain-weave, densely-woven silks used as painting supports during the Tang dynasty were more suited to painting and carried a more refined painting style influenced by Eastern Chinese art rather than Central or South Asian Buddhist art. Imperial endorsement of Buddhism by the Tang court, the inclusion of Dunhuang in the Tang empire and strong trade along the eastern Silk Road would have facilitated such refinement.

The decline of the Tang dynasty provides several reasons why this pattern would have been disrupted, creating a political vacuum in which communication between Dunhuang and the imperial capital broke down, a repression of Buddhism in China and lack of security along the Silk Road hindering eastern Chinese trade to western Central Asia. This disruption explains the reliance on lower quality, recycled silks and the loss of artistic refinement in this isolated area.

The bast fibre ramie (Boehmeria nivea) was identified for the first time as a component of a portable painting from the Mogao Caves, using a sample cross-section and red plate test with PLM. Until now, all non-silk fibres in these paintings were assumed to be hemp. The common perception of bast fibre supports for these paintings is that its use was grounded in economic concerns — bast fibres were cheaper than silk.

However, in many Asian cultures non-silk fibres for painting were the norm. Painting technologies developed to suit the availability of indigenous sources of fibres. In India, where Buddhist wall murals also existed, cloth fabric was a very common support for painting before the arrival of paper technology in the twelfth century. Early banner paintings from Nepal were executed on cloth supports similar to the Tibetan thang-ka, and these styles feature sewn mounts, rather than strip mounting with paste later practised in East Asia. Early photographic evidence shows that paintings currently in the Stein Collection featured sewn mounts before being strip-mounted on arrival at the British Museum.7

By the tenth century, the Buddhist Tanguts who controlled the Dunhuang region rejected vassalage to the successor Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) and political ties became far stronger with areas of Buddhist influence to the immediate south (Tibet) and west (Khotan). Until the eleventh century, when Muslim invasions drove Buddhism from India, there was a steady traffic of Buddhist monks to and from China and India, adding a further spiritual and cultural dimension to the economic trade that Dunhuang facilitated.

Chinese art in the form of portable paintings, as it survives today, is restricted to silk and paper; Chinese painting technology has developed to suit these materials, as has Chinese mounting practice. Rather than seeing bast fibre supports as merely a cheaper form of silk, they appear to offer valuable information regarding the convergence of other cultural and artistic styles at Dunhuang. Because paintings on cotton and bast fibre are not associated with any other surviving Chinese painting style, their use and related painting technology suggest non-Chinese cultural origins impressing their influence on the art of the Dunhuang region from the south and west.

Painting technology

There were numerous signs of workshop practices in the paintings examined in this study. Underdrawing was observed using infrared reflectography. The use of underdrawing reveals a multi-stage process associated with workshop practice, still employed by Buddhist painters in Himalayan cultures. Its presence also suggests multiple artists.

In stark contrast to the painting style found on Tang-dynasty portable paintings from Dunhuang, which feature subtle brush and ink work akin to the literati painting that would emerge shortly in China, tenth-century portable paintings from the Five Dynasties (907–960) and Northern Song feature thick, opaque and layered pigments. Intensity of hue is controlled either by thickness of the paint layer or by combinations of paint layers, usually a colour pigment applied over lead white. Like underdrawing, this is a technique conducive to creating multiple identical images in rapid succession.

It is a notable characteristic of many of the paintings in the Stein Collection that they contain empty painted enclosures for inscriptions. These empty cartouches are further evidence of a workshop practice that produced multiples of the same image. They also suggest that paintings may have been sold and their inscriptions added later according to the identity of the donor. In Eleven-Headed Guanyin, the sutra verses have even been painted by a different hand using a different brush, and different character style, from the donor inscription.

Conclusions

The main conclusion drawn from a comparison of the different painting techniques represented in these paintings is that methods were adapted to suit the physical nature of the supports in use. There is also a distinct shift in style over the centuries, from a refined brush and ink technique lacking evidence of any prescriptive workshop practice that corresponds to the use of high quality, densely woven silks, which gives way to the heavy, opaque pigments and prescribed forms executed on lower quality silks and bast fibre supports after the Tang dynasty.

In examining pigments, supports and painting style, each seems to have been influenced by the isolation of Dunhuang at the decline and fall of the Tang dynasty. As contact with the Tang capital at Chang’an weakened in conjunction with imperial sponsorship of the arts and Buddhism, the Dunhuang region was forced to continue with the resources it had available. Without artistic input from eastern China, influence grew from the south and west where political and economic links were strongest. Portable painting materials and techniques, and even mountings for display, appear by the tenth century to have developed from contact with these cultures.

A PDF version of this paper is available for download. (11.3MB)

Matthew Brack is Baird Fellow in Technical Art History, and Erin Mysak is Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Conservation Science, both at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museums, USA.

NOTES

1. Paul Pelliot et al. Carnets de route: 1906-1908 (Paris: Les Indes savantes, 2008), 294. English translation by the authors.

2. It is important to note that XRF is only a means of elemental analysis and cannot identify compounds. For this reason, it cannot be relied upon solely for the identification of pigments, and will never be able to indicate an organic compound.

3. Unpublished personal communication with Dr. Zhao Shengliang, Dunhuang Academy.

4. Sarah Fraser. Performing the Visual: the Practice of Buddhist Wall Painting in China and Central Asia, 618-960. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 6.

5. Unpublished correspondence with Dr. Robert Mowry.

6. Xu Zheng, ‘Monochrome woven silk’, in Textiles from Dunhuang in UK Collections, ed. Zhao Feng et al. (Shanghai: Donghua University Press, 2007), 160-191.

7. Images courtesy of Dr. Roderick Whitfield.

Turfan Forum on Old Languages of the Silk Road

Ursula Sims-Williams

I recently attended the Turfan forum on old languages of the Silk Road organised in Turfan, by Academia Turfanica, the Turfan Museum and the Bureau of Cultural Heritage of the Turfan Region, 24th–26th October 2010. This was a first visit to China and Central Asia for me, providing a wonderful opportunity to meet Chinese colleagues and visit sites up to now familiar only from the works of Stein, Le Coq and Grünwedel.

The conference consisted of thirty papers on almost as many languages. Li Xiao, Director of Academica Turfanica, delivered the keynote address on the collection at Turfan, while Umemura Hiroshi spoke about the International Project for non-Chinese manuscripts from Bezeklik, with Dieter Maue surveying recent Brāhmī manuscripts discovered there. I gave a paper ‘Revisiting the International Dunhuang Project Database’. Several papers discussed Christian texts: N. Sims-Williams, ‘Medical texts from Turfan in Syriac and New Persian’; E. Hunter, ‘The multi-lingual Christian library at Turfan: Syriac, Sogdian & Old Uigur manuscripts from Bulayiq’; A. Muravyev, ‘Bilingualism in the Christian community of Turfan’.

Before the conference, I was taken on an intensive tour of the region, visiting the Buddhist caves at Bezeklik, Sangim, and Toyuk, in addition to the ancient city of Gaochang. The highspot was visiting the Christian monastery Shuipeng, near the village of Bulayiq, where almost all the Christian Turfan texts were discovered. Due to Le Coq’s imprecise geographical description, this site remained unidentified until 2004.

We also went on a cross-country excursion, driving up a river valley to a site high in the Flaming Mountains in one of the main passes across the mountains which had been an important route to Beiting. Freezing fog, snow and temperatures of minus 7°C did not deter Sogdianists Nicholas Sims-Williams and Yutaka Yoshida from inspecting inscriptions carved in the rock by travellers of ancient times.

The wonderful hospitality by our generous hosts led to this being a truly memorable visit.

Ursula Sims-Williams is Curator of Iranian Languages at the British Library.

Comment on IDP News 34

Professor Lokesh Chandra, New Delhi, India.

The iconography of Buddha on a wooden panel from Khotan, published in IDP News 34, needs a fresh look. The ‘Buddha’ wears jewellry: necklace, arm-band, wrist-band. The vibrations of his samādhi and Maitreya standing to the right with a flask (kuṇḍikā) are significant. None of these three attributes go with Śākyamuni, who does not wear jewellry. The vibrations of samādhi in the halo are of Vairocana. They can be seen in the Japanese mandalas of Garbhadhatu and Vajradhātu Vairocanas. Vairocana preaches the Dharma in the dharmacakra-pravartana mudrā, in the Ming-dynasty (1368–1644) illustration of Shijia Rulai Yinghua Shiji 釋迦如來應化事跡, an illustrated life of the Buddha with citations from various sutras, including the Avataṃsaka texts. Maitreya to the right recalls the Gaṇḍavyūha (443.9) of the Avataṃsaka sutras where Māyā says that she will be the mother of all the thousand Buddhas, beginning with Maitreya and culminating with Abhyuccadeva ‘Colossal Deva’ which is another name of Vairocana. Khotan was an important centre of the Avataṃsaka. The Sanskrit text for the first Chinese translation of the Avataṃsaka was brought to China from Khotan by Zhi Faling 支法領. It was translated by Buddhabhadra by AD 420. Likewise, the Sanskrit original for the second Chinese translation by Śiksānanda was again brought from Khotan by a special messenger sent by Empress Wu Zetian (625–705). Its translation was completed by AD 699. Śiksānanda was a Khotanese monk-scholar who came to Luoyang to translate sutras, returned to Khotan, and came back to Chang’an where he passed away. It is only natural that a wooden panel from Khotan represents Vairocana of the Avataṃsaka denomination.

New Publications

History and Travel

The Silk Roads: A Route and Planning Guide

Paul Wilson

Hindhead: Trailblazer, 2010

446 pp. £14.99

ISBN: 9781905864324

Trailblazer Guide Books

Empires of the Indus

Alice Albinia

London: John Murray, 2009

366 pp. £9.99

ISBN: 9780719560057

John Murray Publishers

Tibet and Buddhism

Travels in the Netherworld

Buddhist Popular Narratives of Death and the Afterlife in Tibet

Bryan J Cuevas

New York: Oxford University Press, 2008

216 pp. US$65

ISBN: 9780195341164

Oxford University Press USA Website

Tibetan Ritual

Jose Ignacio Cabezon

New York: Oxford University Press, 2009

320 pp. US$29.95

ISBN: 9780195392821

Oxford University Press USA Website

A Concise Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism

John Powers

Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 2008

165 pp.US$10.46

ISBN: 9781559392969 1559392967

Snow Lion Publications

Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art

Adriana G Proser

Asia Society Museum

New York: Asia Society; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010

224 pp. £45

ISBN: 0300155662

Yale Books

The Life of Nepalese Buddhist Master Buddhabhadra (359-429 CE.): from Chinese Sources

Mīnabahādura Śākya

Kathmandu: China Study Center, 2009

155 pp.

ISBN: 9789937814706 9937814707

Sacred Economies: Buddhist Monasticism and Territoriality in Medieval China

Michael J Walsh

New York: Columbia University Press, 2009

256 pp. £34.50/US$50

ISBN: 9780231148320

Columbia University Press

108 Buddhist Statues in Tibet: Evolution of Tibetan Sculptures

Ulrich von Schroeder

Chicago: Serindia Publications; Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, 2008

212 pp. US$65

ISBN: 1932476385

Serindia Publications

Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220-589 AD)

John Lagerwey & Lü Pengzhi (eds)

Leiden: Brill, 2010

783 pp. €249/US$369

ISBN: 9789004175853

Brill

Buddhist Art: An Historical and Cultural Journey

Gilles Béguin; Narisa Chakrabongse

Bangkok: River Books, 2009

400 pp. US$70

ISBN: 9789749863879

River Books

Conservation

Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People’s Republic of China, June 28–July 3, 2004

N. Agnew (ed.)

Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, 2010

516 pp. US$89

ISBN: 9781606060131

Getty Museum Store

This volume contains papers on a range of subjects concerning site conservation and management, as well as international collaboration and Silk Road Studies. A free online version of this publication is now available.

Collections

Médecine, religion et société dans la Chine médiévale: étude de manuscrits chinois de Dunhuang et de Turfan

Catherine Despeux

Paris: Institut des Hautes Etudes

Chinoises: Collège de France, 2010

1386 pp. 3 vols.

Collège de France

Textiles de Dunhuang dans les collections françaises

Zhao Feng (chief editor), Laure Feugère & Nathalie Monnet

Shanghai: Donghua University Press, 2010

322 pp. RMB 598

This publication is available in French, and Chinese versions, and will be coming out in English in 2011.

ISBN: 9787811117592/J.100 (French)

ISBN: 9787811117387/J.097 (Chinese)

Catalogues

The Crescent And The Sun

Three Japanese in Istanbul

Yamada Torajirō, Itō Chūta, Ōtani Kōzui

Istanbul Research Institute, 2010

398 pp.

ISBN: 9789759123789

Exhibition Catalogue in Turkish and English

Istanbul Research Institute

Journals

Bulletin of the Asia Institute No 19, 2009

Iranian and Zoroastrian Studies in Honor of Prods Oktor Skjærvø

Edited by Carol Altman Bromberg, Nicholas Sims-Williams and Ursula Sims-Williams

To order:

US$75/90 Individuals/Institutions + shipping

Contact: [email protected] or [email protected]

Bulletin of the Asia Institute

This volume contains papers on the art, archaeology, numismatics, history, and languages of ancient Iran, Mesopotamia, and Central Asia and connections with China and Japan along the Silk Road.

Exhibitions

Secrets of the Silk Road

Penn Museum, Philadelphia

February 5 – June 5, 2011

Secrets of the Silk Road website

This touring exhibition includes over one hundred objects including clothing, textiles, wooden and bone implements, coins and documents, as well as two mummies, the ‘Beauty of Xiaohe’ and ‘Yingpan Man’.

Images and Sacred Texts: Buddhism across Asia

British Museum, London

October 14, 2010 – April 3, 2011

Free Entry

British Museum

Objects from across Asia depicting the Buddha, his teachings and the Buddhist community (the ‘three gems’) are presented in this exhibition. Gold sculptures and paintings of the Buddha, texts on palm leaf and paper, and images of Buddhist monks are on display. The earliest objects are from the first and second centuries AD, and the most recent date to the twentieth century.

IDP Worldwide News

IDP China

Beijing

A number of exhibitions have been organised by the National Library of China with support from IDP Beijing staff. More than 200 rare books and manuscripts went on exhibition at the NLC from 11th June–12th July 2010 in the Third National Rare Books exhibition, including nineteen Dunhuang manuscripts. The most significant of these was the Platform Sutra from the Lüshun Museum collections.

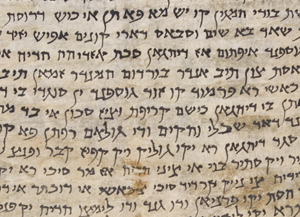

An exhibition of Xinjiang Historical Documents ran from 20th August–20th October 2010 at the Xinjiang Museum, Urumqi. More than forty manuscripts excavated from Turfan and Khotan were displayed, including items written in Chinese, Sanskrit, Kharosthi, Sogdian, Kuchean, Turkic script, Uighur script and other languages. The exhibition proved popular with nearly a hundred thousand visitors. On display was a Judaeo-Persian letter (see image above), which researchers have linked with British Library manuscript Or.8212/166.

Over the year IDP Beijing has welcomed a number of visitors. On 9 February, Thomas Skipper, Counselor for Press and Cultural Affairs of Embassy of the United States of America, Anthony Hutchinson, Counselor for Culture Affairs, and their colleagues Peg Walther and Gu Hong visited the NLC and IDP Beijing. Staff introduced IDP and digitisation workflow, and showed them some Dunhuang manuscripts and the corresponding digitized images on the IDP website and database. The visitors were impressed with the high quality capture of the manuscripts when they compared the original objects to the digital images. On 31st May, Mrs Xia Meishan from Taiwan visited IDP and the NLC Dunhuang and Turfan Documents Reading Room.

Colleagues gave a demonstration on carrying out research on the IDP database and website. On 10th June, Yoon-Hee Hong, Research Professor from the Research Institute of Korean Studies of Korea University and Representative of IDP Korea, visited IDP China and the Dunhuang and Turfan Document Reading Room of NLC. Staff showed her the digitization studio and workflow.

Dunhuang

The Dunhuang Academy and China Minsheng Bank jointly organised an exhibition ‘Art of Dunhuang’ at Beijing’s Yanhuang Art Gallery, which opened on 28th September 2010. The exhibition aimed to introduce the wall paintings and artefacts from the Dunhuang caves to a wider audience through ten original artefacts, sixty-four hand copies of wall paintings and other digital image facsimiles. The exhibition also told the story of the people at Dunhaung who have protected the heritage of the site, as well as showing photographs of conservation work.

The Dunhuang Academy and Zhejiang University jointly organised a consultative conference at the Dunhuang Academy on 24th–25th June to discuss a database and web delivery system for the cave murals and associated data. The conference was supported by the Mellon Foundation. A team of experts, including Susan Whitfield of IDP, were invited to comment on the proposal. By the end of the conference, a fourteen-point action plan was agreed by all participants.

IDP Russia

The Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM) in St Petersburg hosted the annual Permanent International Altaistic Conference (PIAC) in July 2010. Susan Whitfield, Imre Galambos, Vic Swift and Alastair Morrison of IDP attended part of the conference, and joined one of the conference excursions to visit the Department of Conservation and Preservation of the State Hermitage to see the storage facilities where the collection of Turfan wall paintings are kept. They also met with Professor Irina Popova, Director of the IOM, to discuss ongoing collaboration on IDP. A new Memorandum of Understanding was signed by the IOM and British Library for the next five years.

IDP UK staff also met with colleagues at the State Hermitage Museum to discuss collaboration and possible future research and digitisation projects.

IDP Japan

The second meeting of a roundtable event on Dunhuang studies took place at the IOM on 3rd September 2010. Scholars presented ten papers on Dunhuang manuscripts in the IOM collections, collections in Japan and a paper on the irrigation system of the Tangut Xixia state. Titles of papers presented can be found on the IOM website.

Ryukoku University will open a museum in April 2011, to be called ‘Ryukoku Museum’. Situated in front of the Nishi Hongwanji Temple in Kyoto, the museum building was completed in September 2010. Work done by staff at IDP Japan will be on display in the museum, including a digitally reconstructed cave from Bezeklik. The museum will also feature exhibitions on Buddhism, the Silk Road, and the Otani expeditions.

IDP Symposium

An IDP research symposium was organised by colleagues at IDP Japan on 12th–13th July 2010. The event was attended by many researchers from institutions in Kyoto and throughout Japan. Susan Whitfield, Vic Swift, and Imre Galambos of IDP UK also attended and gave keynote papers, respectively on IDP’s collaboration in Japan, IDP’s updated database and British suspicions surrounding the second Otani expedition of 1908-9. Following the symposium, Ryukoku University President Wakahara Dosho and Susan Whitfield signed an agreement renewing the collaboration between Ryukoku University and the British Library concerning IDP. The signing of the MoU was followed by a press conference where questions about IDP and Ryukoku Museum were addressed to both Japanese and British partners. IDP UK staff also visited Kyoto National Musuem where Dr Akao Eikei showed them a selection of Chinese, Japanese and Korean medieval manuscripts.

IDP Germany

Collegium Turfanicum

Japanese colleagues gave lectures in August and September 2010 at the Turfanforschung in Berlin as part of the Collegium Turfanicum lecture series. On 25th August 2010, Professor Takao Moriyasu from Osaka University gave a lecture titled ‘Reconsideration of the epistolary formulae of the Old Uighur letters unearthed from the Eastern Silk Road’. This subject is closely related to his edition of the Old Uighur letters which will soon be published in the series Berliner Turfantexte. On 2nd September 2010 Dr. Kōichi Kitsudō (Ryukoku University, Kyoto) discussed Chinese texts written by Uighurs in his lecture titled ‘Sino-Uigurica I’.

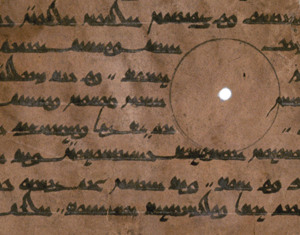

WeltWissen Exhibition, Berlin

The Turfanforschung of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Science and Humanities (BBAW) is participating in the exhibition ‘WeltWissen – World Knowledge’ in the Martin-Gropius-Bau. Dr. Yukiyo Kasai gave a presentation on her current research on the commentary of the Old Turkic Vimalakīrtinirdeśasūtra (see image above) to accompany the exhibition, which is the high point of the Berlin Year of Science. The exhibition is on from 24th September 2010–9th January 2011. See the website for more information.

Digitisation

As part of the digitisation of the Berlin Sanskrit fragments, the digital catalogues are currently being created. The catalogue entries provide information about the title and text as well as bibliographic references to each single fragment. This is particularly useful with regard to the earlier SHT signatures which comprise many sub-numbers and are not described in detail in the first printed catalogues Sanskrithandschriften aus den Turfanfunden in the series ‘Verzeichnis der Orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland’. Furthermore data concerning the type of script, archaeological site and, if applicable, links to other fragments which belong to the same folio are included.

The information is collected from the various editions of existing catalogues of the Sanskrit fragments, and from unpublished material by Anne Peters and Andrea Schlosser. Andrea Schlosser is also preparing the XML files for the IDP website. This work is ongoing, but the preliminary digital catalogues are already available on the IDP website via the catalogue search (the most up-to-date is the German version). The completion is planned for the beginning of 2011, although corrections will continue to be made until the end of 2011.

By the end of the project, all existing Sanskrit fragments of the Turfan Collection will be available for the first time as digital images together with detailed information in the digital catalogues.

IDP UK

People

Vera Nuñez, an MA student, spent two weeks with IDP UK in July 2010. She helped with XML catalogue input, and measuring of Sanskrit fragments in glass.

Yichon Kim from the Research Institute of Korean Studies (RIKS), University of Korea left IDP UK in September after a six-month internship doing photography and imaging work.

Barbara Borghese returned to IDP UK in October 2010 after a two-year career break.

Dr Agnieszka Helman-Ważny from the Asian-African Institute of Sinology at Hamburg University, spent two weeks in December in the IDP studio analysing Chinese manuscripts as part of a three-year German Research Foundation project. She examined manuscripts in the Stein collection to create a paper typology and a map of plant distribution in Central Asia, while also developing terminology on paper production within the context of Western professional literature, and a bibliography on papermaking in East Asian languages. She will also collaborate on an IDP project to create an Oriental fibres reference library, by adding data for inclusion in the IDP database.

Casa Asia Award

Susan Whitfield received the 2010 Casa Asia award on behalf of IDP in Madrid on 2nd November. The award was given to IDP for ‘for its enormous task in the recovery, preservation and exhibition of information and images of the manuscripts, paintings and textiles found in the Chinese city of Dunhuang and of the Silk Route’. The 2010 award was shared with Philippine Senator Edgardo J. Angara.

Susan Whitfield travelled on to Barcelona to give a public lecture at Casa Asia on the Silk Road and the Dunhuang Library Cave. She also discussed with Casa Asia the possiblity of collaboration on joint projects and a Spanish IDP website.

Collaboration

Susan Whitfield and Alastair Morrison met with Professor Li Xiao at the Turfan Academy during their June visit to China. Professor Li explained that the Academy will soon be developing a database, and would be interested in collaborating with IDP. They were also shown newly-excavated material housed in the storage facilities at the Academy.

Conservation

Barbara Borghese started work on a project in December 2010 to collect, organize and to make available Oriental fibre analysis data and to create an Oriental fibres reference library to add to the IDP website. The work will provide resources for scholars, scientists and anyone interested in Silk Road and Central Asian material.

Server Upgrades

All the IDP servers worldwide have been upgraded to 4D version 11 over 2010. This is fully Unicode compliant which will allow better rendering of multilingual characters on the IDP websites.

Visit from Chinese Scholars

Using travel funds generously provided by the Sino-British Fellowship Trust, three scholars from China paid a working visit to London in August 2010. Wubuli from the Xinjiang Cultural Relics Bureau, Su Bomin from the Dunhuang Academy, and Liu Bo, IDP Manager at the National Library of China spent a week visiting Central Asian collections in London institutions. They spoke at an informal seminar at the Courtauld Institute: Wubuli spoke of his involvement with the UNESCO Silk Road project; Su Bomin introduced the conservation department strcuture and projects at the Mogao Caves; and Liu Bo gave a report on paper conservation at the NLC.

IN THE NEXT ISSUE — LAUNCH OF IDP KOREA AND KOREAN WEBSITE

Central Asian collections in Korea and research projects on Korea and the Silk Road.

This digital version of IDP News is based on the print version of the newsletter and some links and content may be out of date.

This issue, No. 35, was published Spring-Summer 2010.

Editor: Alastair Morrison

Picture Editor: Rachel Roberts

ISSN 1354-5914

All text and images copyright their creators or IDP, except where noted. For further information on IDP copyright and fair use, please visit our Copyright page.

For further information about IDP please contact us at [email protected] or visit our Contact page.