In July 2016, Dr. Miki Morita started work as the Georgetown-IDP Postdoctoral Research Fellow for North American Collections with the remit of researching artefacts from the eastern Silk Road held in public and private collections in North America for inclusion on IDP. Funded by the Henry Luce Foundation and under the supervision of Susan Whitfield (IDP UK) and Dr. Michelle Wang (Georgetown University), her work systematized and greatly expanded that started previously by IDP which had resulted in items from the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institute, Morgan Library and Museum, Princeton East Asian Library and University Art Museum, the Lo Collection, and UCLA becoming available online. In this double issue of IDP News, we show some of the results of her research and success in starting to make many more artefacts from North American collections available through IDP.

The Georgetown-IDP Project

Michelle C. Wang

The Georgetown-IDP Project for North American Collections developed from conversations between Susan Whitfield, Miki Morita and myself that began in spring 2015, following Susan’s trip to Georgetown University to deliver a well-received talk on IDP and the landscape of international collaboration in the Critical Silk Road Studies Seminar, a year-long series of events supported by the Mellon Foundation that I co-organized at Georgetown in 2014-2015. At that time, it quickly became obvious that the combination of Miki’s prior experience in similar projects and the resources and academic community for Silk Road studies at Georgetown and in the Washington, DC area were an ideal fit for convening this project, representing a major step forward for the large-scale incorporation of Silk Road artefacts in North American collections into the IDP database for the first time. With the support of funding from the Henry Luce Foundation, the Georgetown-IDP Project for North American Collections began in July 2016. Sincere thanks are due to Program Director Helena Kolenda for her robust enthusiasm for the project and to the Luce Foundation for the grant that made this possible.

Through dedicated outreach, the project has yielded more than 1,300 objects from over 30 institutions. The Dunhuang Foundation US supported travel for our group meetings in Washington, DC last November and in New York City this April to discuss the progress of the project and to view paintings and sculptures at the Brooklyn Museum and Metropolitan Museum of Art. Closer to home, Miki and I examined paintings in Washington, DC’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the Turfan slides from the Führerprojekt in the National Gallery of Art this spring. The Dunhuang Foundation US also supported Miki’s most recent research trip to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Yale University Art Gallery and Manuscripts and Archives of the Yale University Library.

The first year of the project came to a successful close with her lecture ‘Highlights of the Georgetown-IDP Project 2016-17’ to a packed audience at the Sackler Gallery on May 31.

The project has been based in the Department of Art and Art History at Georgetown, which has contributed office space, administrative support, and access to library resources. We are grateful to department chair Al Acres, department administrator Darlene Jones, department coordinator Maggie Ayres, and colleague B. G. Muhn for their unwavering support, assistance, and interest in the project. Ding Ye, Asian Studies librarian in Lauinger Library, has been instrumental in tracking down specialized research materials pertaining to the material culture of the Silk Road. Former Art and Art History librarian Anna Simon was particularly helpful in publicizing and supporting the project in its early stages.

Moving forward, plans are currently underway for a series of on-site workshops in museums and libraries that will provide opportunities for hands-on engagement with a selection of these artefacts. They reflect not only the cultural heritage of the premodern Silk Road in a diverse range of media but also its modern discovery and the twentieth century taste for collecting Central Asian antiquities. Through this series of events, we hope to bring together curators, librarians, conservation specialists, faculty, and graduate students in a rewarding, in-depth exploration of the rich heritage of Silk Road collections in North America. Stay tuned!

Michelle C. Wang is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art and Art History at Georgetown University.

An Overview of North American Collections

Miki Morita

Introduction

Since its start in July 2016, the Georgetown-IDP project on North American Collections has made great progress thanks to generous support from the Luce Foundation and active participation of over thirty institutions. It is with great pleasure that I present the following summary of this ongoing project in this special issue of IDP News, made possible by the Dunhuang Foundation US. The project’s progress owes a great debt to the collective efforts of all participating institutions.

During my time as Georgetown-IDP Research Fellow, I have contacted institutions with known holdings of IDP-related pieces. Information about the project was also distributed to various professional organizations through listservs. In addition, I contacted most institutions listed in the American Alliance of Museums. Altogether, the project has reached out to more than 500 North American institutions.

To date, more than 1300 manuscripts, objects, and archival materials have been identifed as fitting within the scope of IDP. This number includes very fragmentary pieces and increases if we include collections that we have not had the opportunity to examine. Posts on the IDP Blog are introducing pieces as they become part of IDP.

Paths to North America

But how did these pieces end up in North America? Similar to the situation in Europe and East Asia, there are collections resulting from expeditions as well as those purchased from various sources. Introduced here are several examples of explorations in the twentieth century.

Langdon Warner (1881-1955) was a professor and curator at Harvard University. During the rst Fogg Expedition (1923-4), Warner and Horace H. F. Jayne (1898–1975) of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PAM) traveled first to Kharakhoto, and then, Warner alone, to Dunhuang (Hopkirk 1980: 209-22). Their acquisitions, now in the Harvard Art Museums, included a statue of an attendant bodhisattva (Harvard Art Museum, 1924.70) and wall paintings from Dunhuang. [Ed. Note: Interestingly, although many archaeologists from this imperial age acquired items from Dunhuang, it is Langdon Warner who receives most criticism, with visitors to the caves being shown the places from where these items originated. Of course, Aurel Stein is also often vilified when it comes to his acquisitions from the Dunhuang Library Cave.] The Museum also houses many sculptures from Kharakhoto. A stucco head from Turfan in PAM was donated by Horace Jayne (PAM, 1928-23-1).

Ellsworth Huntington (1876-1947) was a geographer interested in the effect of climate change on human civilization. He was appointed by the Carnegie Institution of Washington to assist Professor William M. Davis (1850-1934) of Harvard University on an expedition (1903-04) led by Raphael Pumpelly (1837-1923). On a second visit (1905-06), he joined Robert L. Barrett (1871-1969), Davis’s wealthy student and funder of the expedition (Chorley 2009: 282). His collection, including a few archaeological artefacts and geological specimens along with his photographs, is now in Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. Harvard University College Library and the British Library also have small collections of manuscripts from Huntington (Sims-Williams 2012).

Oscar T. Crosby purchased about 150 manuscripts in Khotanese and Sanskrit in Khotan in 1903. These are now in the Library of Congress (Emmerick 2011).

James C. M. Lo 羅寄梅 (1902-87) and Lucy Lo 羅先 (née 劉), also donated important collections of manuscripts, artefacts and photographs to the United States (Chen and Tomasko 2010b: 2). Thousands of their photographs are now housed in the Lo Archives. Most of the manuscripts (many of which were given them by Zhang Daqian) have been transferred to the East Asian Library Collection of Dunhuang and Turfan Materials, which also has a manuscript and hemp sutra wrapper collected by by Guion M. Gest (1864-1948). (Gest was founder of the Gest Engineering Company and a frequent visitor to China. The Princeton University Art Museum also houses several manuscripts and other objects. The 158 manuscripts in the Collection include those in Chinese, Tangut, and Old Turkic. These manuscripts have been available on IDP since 2008 (IDP News 30). The latest information on non-Chinese manuscripts will be added to the IDP database through the current project.

Another important group of artefacts dispersed in various collections in North America originates from the German expeditions in the early twentieth century. Pieces identified to date mainly consist of paintings, sculptures, and fragmentary murals from Turfan and Kucha. Although I have not been able to review all the provenance records, many of them can be traced back to Albert von Le Coq (1860-1930), who participated in the second to fourth German expeditions, and was director of the Department of Indian Art at the Berlin Ethnological Museum (1923-25). The dispersal is thought to have been precipitated by a financial crisis that von Le Coq faced during his tenure. Around fifty mural fragments that were considered as less significant along with some duplicates were sold through art dealers. It was a difficult decision for Le Coq, who had been planning an exhibition of the Turfan collection during a time of high inflation rates and a depreciating German Mark (Lee 2015: 11-12).

In addition to these, some pieces originating from the 1927-28 expedition of the German-Swiss team, Emil Trinkler (1896-1931) and Walter Bosshard (1892-1975), are now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Gropp 1974). Pieces from the Khotan region associated with this expedition were either excavated or purchased in a local ‘curiosity shop’ where pieces discovered by local treasure seekers were sold to foreign visitors (Waugh and Sims-Williams 2010).

Apart from these expeditions, other artefacts ended up in North America in various ways as gifts and purchases after long journeys from northwestern China. Of course, it must also always be remembered that, just as in the European collections, there is also the possibility of some of the objects being forgeries (Whitfield 2002).

Miki Morita is Georgetown-IDP Postdoctoral Research Affiliate.

Highlights from North American Collections

The following section introduces selected objects relevant to IDP in the North American collections. As this is an ongoing project, there are many pieces that await curatorial review or further research before they can be con dently dated or associated with an archaeological site. Basic information on the objects introduced here has been provided by their respective holding institutions.

Dunhuang

North America was among the recipients of the dispersed Dunhuang artefacts and collections include manuscripts, prints (eg. Cincinnati Art Museum, 1992.139; Royal Ontario Museum, 927.24), sculptures (eg. Princeton University Art Museum, y1986-110), and paintings. Many of the Chinese manuscripts are Buddhist texts, among them major titles such as The Sutra of Golden Light and The Perfection of Wisdom Sutra. Holders include the C.V. Starr East Asian Library of both Columbia University and University of California, Berkeley.

A relatively recent discovery is a scroll of The Sutra of Golden Light held by Scripps College in California. Patches on the back contain Tibetan text. According to Sam van Schaik of IDP, these patches were taken from a single manuscript of the prātimokṣa, the monastic rules that are recited twice a month.

A scroll of the Subcommentary on the Quadripartite Prātimokṣa (四分戒本疏) by Śramaṇa Hui (沙門慧) is held at Philadelphia Museum of Art (1968-227-1). The collators of the many copies of this text from Dunhuang are associated with Chos-grub, or Facheng (法成), a bilingual Buddhist monk and translator active in Dunhuang in the mid-ninth century, when the area was under Tibetan rule. This scroll was one of a handful of extant copies of the fourth scroll, and has contributed to the reconstruction of the entire scripture (Mair 1984).

An intriguing pillar from Gansu Province in the collection of the Field Museum in Chicago bears inscriptions concerning a Sino-Tibetan war in the eighth century (The Field Museum, 121938). In this war, Shibao 石堡, which had been conquered by the Tibetans in 741, was recovered by General Koso Khan (Ch. 哥舒翰 d. 757) in 748. The museum also holds rubbings of the inscription (The Field Museum, 12938).

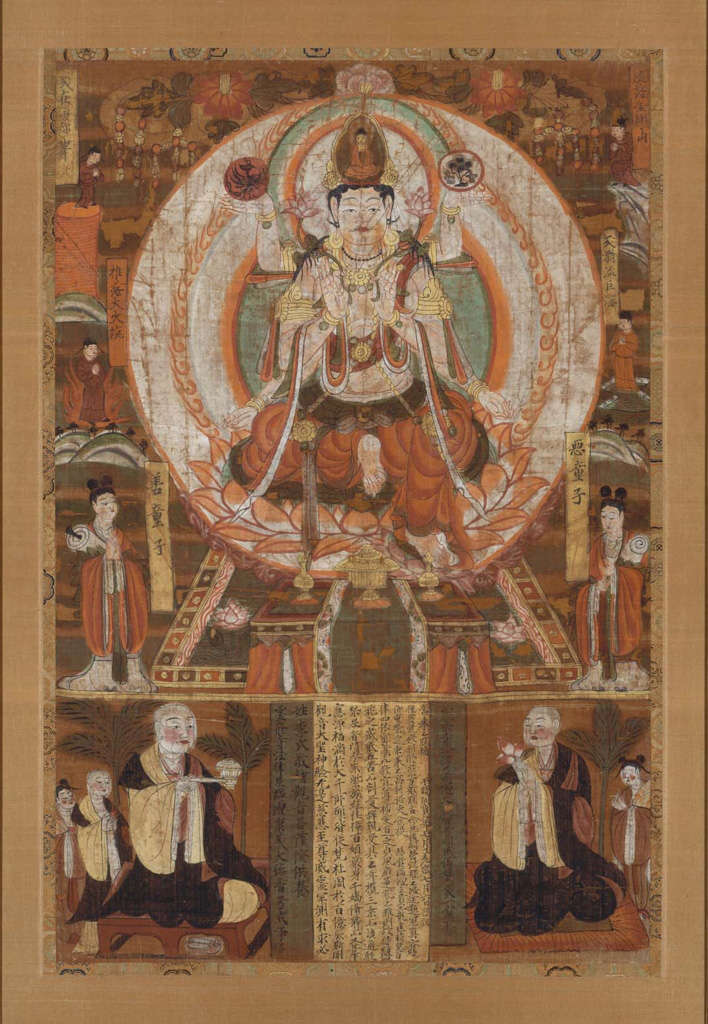

In addition to well-known pieces in the Harvard Art Museums (eg. 1943.54.1) or the Freer and Sackler Galleries (eg. F1930.36, see Cohen 2002), other North American collections hold various pieces including at least four paintings of Avalokiteśvara. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, holds a large painting on silk of Avalokiteśvara as Saviour from Perils, dated to 975,. The donor figures shown at the bottom are identified by the inscriptions as the nuns Jiejing 戒淨 of Lingxiu Monaster 靈修寺 and Mingjie 明戒 (Fig. 1). Behind Avalokiteśvara, one can see the scenes of perils from which Avalokiteśvara was believed to grant salvation, such as ‘falling from the Diamond Mountains’ and ‘Drifting in Vast Seas.’ The painting’s colophon mounted on the verso records that this painting was formerly in the collection of Duanfang 端方 (1861-1911), a government official of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) and a well-known collector and connoisseur of Chinese antiquities (Rong 2001, 58-59; Wu Tung 2003, 132-133; Freer and Sackler Galleries, ‘Duanfang’).

Other bodhisattvas are depicted on other banner paintings. The painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (p. 8), shows a deity holding a peacock feather. Because of this attribute, the deity has been tentatively identified as Mahāmāyūrī, the Great Peacock Wisdom Deity.

Turfan

The first piece I will introduce from Turfan is a fragmentary painting on cotton, prepared with plaster, showing a goddess with an offering. It is in Yale University Art Gallery (Fig. 2). The figure shows clear stylistic features associated with the Uyghur period of the Turfan region, and based on this, the painting is probably dated to the tenth to eleventh centuries (Russell-Smith 2005: 196). According to the gallery’s archives, it was purchased from Albert von le Coq in Berlin by Ada Small Moore (1858–1955), who was the gallery’s major donor of Asian art (Matheson 2001, 78). Currently the painting is associated with Bezeklik in its provenance record, yet it was probably discovered in Gaochang (Kocho) because it appears in Grünwedel’s archaeological report on the first German expedition as a painting discovered in temple λ (Grünwedel 1906, 99; Tafel XVII Fig. 2 a, b). The other side also shows a female deity.

Other typical examples of paintings from the Turfan region are murals of bodhisattvas (Honolulu Museum of Art, 001447.1; Penn Museum, C412). There are at least ve similar bodhisattva heads scattered across the North American collections. According to the archival records of some of these pieces, they were purchased from the German collection and originate from the Bezeklik Caves. Bezeklik Cave 9, which is indicated on the murals’ verso, still retains wall paintings of bodhisattvas that are very similar to this group.

There are other very intriguing pieces from the Turfan region including an iron plaque with an image of a standing Buddha (Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, B87B3) and sculptural heads from Karashahr and Shorchuk (eg. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 33-1539). The appearance of the standing Buddha is very similar to those of buddhas typically associated with the Bezeklik Caves from the Uyghur period, characterized by a plump face in the three-quarter view, the folds of the robe, and above all, personal adornments on the body. While it is likely to be a votive plaque, the absence of similar comparative pieces from the same region makes it difficult to ascertain its original context. There are of course manuscripts from Turfan in North American collections, especially in the East Asian Library of Princeton University (Chen and Tomasko 2010a).

Kucha

The murals from the Kizil caves form a notable group of archaeological findings in the North American collections (Lee 2015; Morita 2015). At least forty-seven fragments from these caves are dispersed between several collections in North America, including Seattle Art Museum (33.1679; 33.168) and Detroit Institute of Art (28.67). As in the case of the Turfan murals, the German collection served as the source of these pieces, and records from the expeditions have helped us with identifying the murals’ original locations. Seventeen murals are housed in the Smithsonian Institution. Ten were probably from Cave 224 based on the verso inscriptions and painting styles.

Among the other pieces, there is a fragment showing two deities (see front cover). This exquisite piece does not contain any inscription on its verso, yet has been associated with Cave 205 by Ueno Aki with little supporting evidence (1980, 50-51). Three other murals, unfortunately lost during World War II, could possibly help identify the origin site. All three show the same distinctive background of bejewelled drapes, the details of the crowns and other ornaments and the white highlighting of the dark-skinned figure.[1] These similarities suggest that they might all originate from the same cave.

The Varṣakāra fragment and ‘Two Deities’ are both considered to have come from Cave 205 (Kumagai 1954, 125-126). Although the find site of the third piece, ‘Deity with a Reliquary’, is simply recorded as ‘Kyzil, Mayahöhle, Kloster’ (Kizil, Maya Hall, Cloister), its striking similarity to ‘Two Deities’ is strong proof that this mural also belongs to Cave 205. It is therefore reasonable also to associate the Smithsonian’s mural with Cave 205. As to the mural’s location inside the cave, I propose the lunette of the main hole beside enthroned Maitreya (Grünwedel 1912, 163).

There are two additional murals from other sites in the Kucha region. The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco holds the beautiful ‘Head of a Buddhist Deity’ from Simsim Caves (Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, B79D2). German inscriptions on the verso record the original site and, according to the archives, it was a gift from Albert von Le Coq to Lucien Scherman, father of the piece’s donor Dr. Richard P. Scherman. Besides this mural, the Museum holds a small wooden sculpture from the Kucha region (2004.23). The other mural with a seated Buddha figure is now housed in the Brooklyn Museum (35.1963). This piece is from Kumtura, and also bears German inscriptions on its verso.

[1]: The pieces from Berlin are: ‘Two Deities or Worshippers Holding a Reliquary, Wooden structure above’, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, IB9047a,b.; ‘Deity with a Reliquary’, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, IB9047; Foto Marburg & Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Photothek, FMLAC8809_13; ‘Varṣakāra Reports the Death of the Buddha to King Ajātaśatru’, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, IB8437.

Khotan and Kroraina

Manuscripts from the oasis kingdoms of Khotan and Kroraina in the southern Taklamakan Desert are also found in North American collections. In addition to Crosby’s collection in the Library of Congress, mentioned earlier in this report, the Tozzer Library of Harvard University holds a major collection of manuscripts in Khotanese, Sanskrit, Prakrit and Tibetan. These fragmentary manuscripts are conserved in over five hundred clear sleeves.

The Ellsworth Huntington Papers in Yale University’s Manuscripts and Archives also contain a small number of manuscripts in Khotanese, Tibetan, Prakrit (Kharoṣṭhī) and Sanskrit. Huntington collected, was given, and purchased these manuscripts and artefacts from sites such as Khadalik, Niya and Endere (Huntington 190-46).

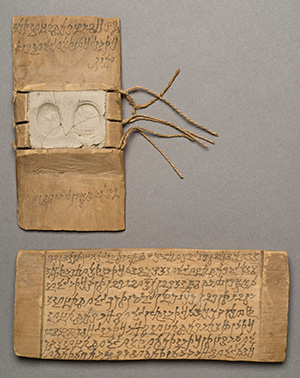

Middlebury College Museum of Art holds a legal document in the double-wedge form typical of 2nd-4th century Kroraina (Fig. 3). Written in Gāndhārī using Kharoṣṭhī script, this piece was probably discovered in Niya, and its contents concern a dispute and settlement over the ownership of a slave called Lepata, who was worth three camels. The judgement is written on the inside of two wooden board which were secured by string and clay seals. A summary was written on the outside, but the judgement inside was secured until the seals were broken (Whitfield and Sims-Williams 2004, 151).

As to other types of archaeological objects, a number of fragmentary paintings and sculptures from these sites ended up in North America. An especially noteworthy collection is held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Museum purchased part of the Trinkler collection. Photographs taken in 1922 by the then British Consul-General in Kashgar, Clarmont Percival Skrine (1888-1974), show two of the Museum’s pieces (MMA, 30.32.6 and 30.32.20; Clarmont P. Skrine, Royal Geographical Society, S0005895 and S0005897; see also Waugh and Sims-Willams 2010, figs.10 and 11). They were arranged on the shelves of a shop in Khotan run by Badruddin, who was one of the elders representing local merchants in dealing with officials and British consuls (Waugh and Sims-Willams 2010, 69-73). In total ninety-eight pieces from sites such as Rawak, Yotkan, and Dandan Uilik are associated with Trinkler, and selected pieces will be included in the IDP for this phase of the project. There are also five mural fragments in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (M.73.48.142-146).

Kharakhoto and pieces associated with Tangut culture

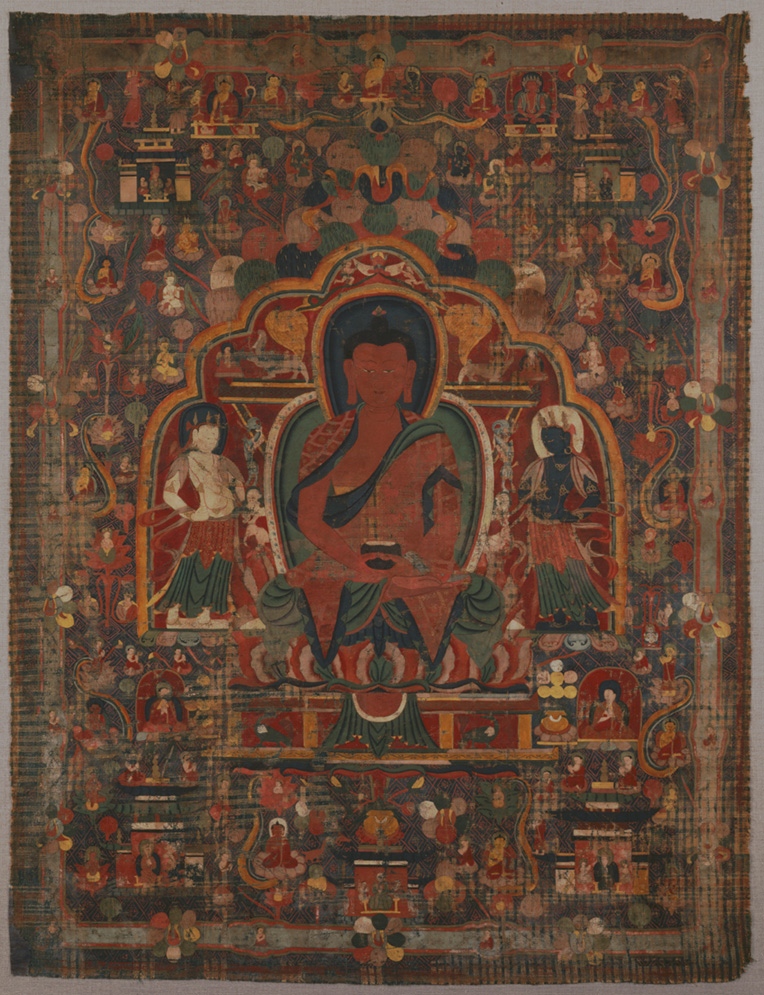

Pieces from Kharakhoto and those associated with the Tangut empire (Xixia) in the North American collections should not be overlooked. Fragmentary printed texts in Tangut in the collection of the Princeton University’s East Asian Library have been a part of the IDP database prior to the current project. As previously mentioned, a number of sculptures, figurines, and wooden objects from Kharakhoto were acquired on Harvard’s First Fogg Expedition led by Langdon Warner. In addition, there are at least three thangka directly and indirectly associated with the Tanguts (Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.72; Newark Museum, 96.97; Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, 1992.59). It has been proposed that the plaid cloth of Amitābha in the Newark Museum (Fig. 4) links this piece to those from Kharakhoto from the thirteenth century. (Reynolds 1999, 245).

Textiles

There are excellent collections of textiles in North America, and I am excited that such ne pieces will be included in IDP. Besides many beautiful fragments (eg. LACMA, M.2007.32.1), other textiles include embroidery of a Celestial Musician (Cleveland Museum of Art, 1987.145) and a woman’s boots (Art Institute of Chicago, 1999.503a-c). One of the most exquisite pieces is the Prince’s Coat in Cleveland Museum of Art (Fig. 5), probably worn by a little boy, possibly of the Tang imperial family. The silk bears a pattern of confronted ducks in roundels, with pearl collars, ying scarves, and a jewelled necklace in their beaks: all these motifs show a Sassanian in uence. The cloth is thought to have been woven in eastern Iran or possibly Sogdiana, and was once accompanied by matching trousers. The under trousers (Cleveland Museum of Art, 1996.2b) were made of Chinese white silk with patterns of rosettes, blossoms, and birds, lined with Chinese brown silk damask that was also used for the lining of the coat (see Mackie 2015: 65-69, Watt and Wardell 1997).

Photograph archives

Finally, there are important photographs that capture archaeological sites and cultural relics of Dunhuang and Xinjiang. In addition to those taken by previously-mentioned explorers such as Warner, Huntington, and the Los, there is another intriguing set of colour slides showing pieces from the German collections. This group of 145 slides is part of the National Gallery of Art (NGA)’s 3,572 slides from the Führerprojekt.

Führerauftrag Monumentalmalerei (Führer’s Order for Monumental Paintings), or Führerprojekt, was a photographic survey of immovable works of art, ordered by Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) in 1943. The purpose of this project was to prepare for the reconstruction of damaged art works after the expected Nazi victory, and the photographs’ quality was thus exceptionally high (Kuesntner and O’Callaghan 2017, 375). While the set of slides belonging to Hitler was destroyed by the Russian Army, the rest were mainly kept by those who worked for the project. In 1947, Kurt Wolff (1887-1963), a half-Jewish German immigrant and the founder of Pantheon Books in New York, initiated efforts to collect them, and after almost two years of assiduous work, he had assembled 3,572 slides, along with lists of the slides, official receipts, an additional 1,038 stained-glass slides, and 3,300 monochrome photographs (Kuesntner and O’Callaghan 2017, 376; 382). The former three eventually came into the collection of the NGA in 1951, and duplicates of 528 slides were made around 1960 to supply the Führerprojekt slides remaining and reassembled in Germany (Ibid: 382-385). A selection of the Führerprojekt slides, including murals from Kucha, are accessible through the NGA’s website.

As previously stated, the Georgetown-IDP Project on North American collections is an ongoing project, and there might be new discoveries as information on the project spreads. We welcome your thoughts on the pieces introduced here, or any suggestions on additional pieces that might be suitable for inclusion in the IDP database.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — Pieces from Dunhuang?

Susan Whitfield

Lot 0171 at the Christie’s London sale on 15 May 2007 (pictured right) was described as ‘An Extremely Rare and Important Tang Dynasty Painting on Silk.’ It was offered for sale by the Andrews family, descendants of Fred H. Andrews (1866-1957), long-term assistant and friend of M. Aurel Stein (1862-1943). Described as being handed down from his collection and therefore belonging to the family, the piece was purchased for £84,000 for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York by James Watt, then Chair of the Department of Asian Art.

The sale caused some consternation as this was a fine piece, probably from Dunhuang and from the Stein collection. Its emergence and sale raised a number of questions regarding the provenance, circulation and conservation of Silk Road artefacts.

Andrews had been responsible for unpacking the material from Dunhuang and other Central Asian sites after Stein’s second expedition. Curators at the British Library and the British Museum, myself included, felt it was possible that this was a piece from the Stein collection from Dunhuang worked on by Andrews and inadvertently remaining in his possession after the other pieces had been acquisitioned into the British Museum and National Museum of India collections.

Stein and others regularly handed over or dispatched manuscripts and objects by post to specialist colleagues across Europe for research. Some of these were never returned. This was seldom due to intent: deaths, wars, or simply forgetfulness meant that small parts of the collections found new homes. It was felt that the banner offered for sale might have a similar story to tell.

Over the two days before the sale I scoured Stein’s descriptions of the banners in his published and unpublished works but nothing matched this piece. The peacock feather held in the deity’s right hand — an unusual iconographic motif —would almost certainly have been noted in any description, however brief. But I could find no mention of this in any of Stein’s or Andrew’s writings, published or unpublished.

Of course, this was not conclusive. I did not review all the unpublished material. Also, many manuscripts and painting fragments were used as patches or reinforcement for other pieces and it is possible that this piece only found a separate identity after conservation. Other pieces were crumpled and fragmentary due to their storage in the Library Cave and only later was conservation time and expertise available to restore them. This piece has considerable loss on one side, indicative of its having been folded. The triangular headpiece showing a seated Buddha was separated from the rest of the banner – it is possible they did not originally belong together. They were conserved on a single backing for the sale.

Although it was assumed at the time that this piece came from Stein’s first visit to Dunhuang Mogao, in 1907, there is also a small possibility that it was acquired on his second visit in 1915. Although Stein only records his acquisition of manuscripts, it is possible that this piece was rolled up among other material and not noticed until later.

A third possibility is that Andrews was given it by Stein or acquired it from elsewhere. Although the collections of these early explorers were placed into public institutions who had provided the funding, there were exceptions. So, for example, the German explorers sold several pieces of Central Asian wall paintings to local dealers: many of these were purchased by private collectors and some are now in institutions in North America, as Miki Morita discusses here (p.3).

Two other items in the Museum’s collection were acquired in 1926 by these means. Both are woodblock printed prayer sheets dating from the tenth century. Many such prayer sheets were found in the Dunhuang Library cave, some from the same woodblock. One of those in the Museum shows Avalokiteśvara and an inscription dating its production to AD 947. The records show that it came into the Museum through the Morgan Library in New York as a gift from Paul Pelliot. The other print, showing Mañjuśrī, was also acquired in 1924 from the Asian art dealership Yamanaka & Co. However, it is certainly from Dunhuang and most probably also from Pelliot — we know the dealership had an agent in Paris and a branch in New York.[1]

Incidentally, there is also a print in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (ROM), which originally belonged to the Stein collection. Unlike these two, it was acquisitioned into the British Museum collection in 1919 but was then acquired by ROM in 1924.[2]

However, regarding the painting, we have no record of such a gift from Stein — nor would it be legitimate given that his finds were considered to ‘belong’ to the funders and therefore not his to give away. But it is difficult to imagine where else Andrews could have acquired it. He did not travel with Stein to Central Asia and, as far as I know, there was not a market for such items at this time in India or Britain.

The evidence, therefore, suggests that it was part of the collections acquired by Stein from Dunhuang but that it was not in a state where it could be treated as a distinct object when the paintings were described by Stein in Serindia. It is possible that it was among those items sent to India which Andrews worked on while there. But Andrews kept many items relating to the expeditions up to Stein’s death, as shown by a letter he sent to Stein in 1942. It concerns a request from Stein for some research material which he believes is with Andrews:

After much searching among rolls of paper. I have found the original sketches by Afraz Gul and am sending your tracings of the shrines. … I … can only express my great regret that I had not been able to find these drawings earlier. The accumulation of material during the many years of our work together makes the search for a particular item a long business, as you too know.[3]

This lends credence to the possibility of the painting, probably crumpled up among other items, having been inadvertently neglected and possibly only discovered by Andrews much later – or, indeed, only discovered by his family when sorting out his possessions after his death in 1957.[4]

We will probably never know, but it is fortunate that when painting finally emerged it was been acquired by a major collection and is therefore now conserved, catalogued and available for study.

Notes:

[1] See W. Perceval Yetts. 1924. ‘Messrs. Yamanaka and Co.’ Burlington magazine for Connoisseurs 45.261: 315-6. In 2015 the Museum held an exhibition of Japanese artworks: ‘Discovering Japanese Art: American Collections and the Met.’ This included a section on those acquired from the company: ‘Yamanaka & Co. Bringing Masterworks to America.’ See http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/ listings/2015/discovering-japanese-art]. Other pieces, such as the painting of the Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara in the Freer (F1930.36), were also acquired through Yamanaka (Cohen 2002: 26).

[2] This will shortly be available on IDP. It was acquisitioned as 1919,0101,0.241, Stein site no. Ch.000185a. Ch.000185c and d are in the Museum’s collection (1919,0101,0.242 and 243.) Ch.000185e-f are listed by Stein as having gone to India, so should be in the collections of the National Museum of India, New Delhi. It is possible that b was also sent to India.

[3] MS Stein 60f.163, letter dated 25th July 1942. Mian Afraz Gul of the Khyber Rifles, accompanied Stein on his third expedition. He had trained as a military surveyor and also had accompanied Stein on expeditions to the northwest frontier. I do not know the current whereabouts of these sketches.

[4] A small group of Stein’s papers was bequeathed to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 1958 after Andrews’ death. These were passed on the Bodleian Library in 1988 where they remain. As far as I know, they do not include the sketches. Thanks to Helen Wang for this information.

The Georgetown-IDP Project on North American Collections would like to thank the following institutions for their cooperation during 2016 and 2017.

Art Institute of Chicago

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Brooklyn Museum

C.V. Starr East Asian Library, Columbia University

C.V. Starr East Asian Library, University of California, Berkeley

Cincinnati Art Museum

Cleveland Museum of Art

Detroit Institute of Arts

East Asian Library and the Gest Collection, Princeton University

Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College

Field Museum of Natural History

Freer and Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution

Harvard Art Museums

Honolulu Museum of Art

Library of Congress

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Middlebury College Museum of Art

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

National Gallery of Art

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Newark Museum

Ohio State University

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

Penn Museum

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Princeton University Art Museum

Royal Ontario Museum

Seattle Art Museum

Tozzer Library, Harvard University

University of Chicago Library

Yale University Art Gallery

Yale University Library

Selected Bibliography on North American Collections

- Balachandran, Sanchita. 2004. ‘Research into the Collecting and Conservation History of Chinese Wall Paintings from Dunhuang in the Harvard University Art Museums.’ thesis (certificate in conservation), Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies.

- Brack, Matthew and Erin Mysak. 2010. ‘A Technical Study of Portable Tenth-Century Paintings from Dunhuang in US Collections.’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museums. Accessed June 29, 2017. PDF

- Bullitt, Judith Ogden. 1989. ‘Princeton’s Manuscript Fragments from Tunhuang.’ The Gest Library Journal 3 (1-2): 7-29.

- Carter, Martha L. 1998. ‘Three Silver Vessels from Tibet’s Earliest Historical Era: A Preliminary Study.’ Cleveland Studies in the History of Art 3: 22-48.

- Chen Huaiyu 陈怀宇. 2004. ‘Pulinsidun suojian Luoshi cang Dunhuang Tulufan wenshu’ 普林斯顿所见罗氏藏敦煌吐 鲁番文书 [Manuscripts from Dunhuang and Turfan in the Private Collection of James and Lucy Lo that I Examined]. Dunhuangxue 25: 419–441.

- Chen, Huaiyu and Nancy Norton Tomasko, eds. 2010a. ‘Chinese-Language Texts from Dunhuang and Turfan in the Princeton University East Asian Library.’ The East Asian Library Journal 14 (2): 1-13.

- Chen, Huaiyu and Nancy Norton Tomasko, eds. 2010b. ‘A Descriptive Catalogue of the Dunhuang and Turfan Materials.’ The East Asian Library Journal 14 (2): 13-208.

- Cohen, Monique. 2002. ‘Genuine or Fake?’ In Whitfield: 22-32.

- Crosby, Oscar T. 1905. Tibet and Turkistan. New York and London: Knickerbocker Press.

- Czuma, Stan. 1993. ‘In Honor of Evan H. Turner: Tibetan Silver Vessels.’ CMA Bulletin 80: 131-135.

- Edgren, Sören. 1985. Chinese Rare Books in American Collections. New York: China Institute in America.

- EI: Encyclopaedia Iranica, online edition.

- Emmerick, Ronald. E. 1968. The Book of Zambasta: a Khotanese poem on Buddhism. London: Oxford University Press.

___ 1969. ‘The Khotanese Manuscript ‘Huntington K’.’ Asia Major 15: 1-16.

___ 1986. ‘Another Fragment of the Sanskrit Sumukhadhāranī.’ In Deyadharma: Studies in Memory of Dr. D. C. Sircar, edited by G. Bhattacharya, 165-67. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications.

___ 2011. ‘Crosby, Oscar Terry’ EI. WEBSITE - Freer and Sackler. 2016. ‘Duanfang 1861-1911: Collector of Chinese Art.’ WEBSITE.

- Gluckman, Dale Carolyn. 2000. ‘For Merit and Meditation: Selected Buddhist Textiles in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.’ Orientations 31(6): 90-98.

- Granoff, Phyllis. 1968. ‘A Portable Buddhist Shrine from Central Asia.’ Archives of Asian Art. 22: 80-95.

- Grünwedel, Albert. 1906. Bericht über archäologische Arbeiten in Idikutschari und Umgebung im Winter 1902-1903. München: K. B. Akademie der wissenschaften.

___ 1912. Altbuddhistische kultstätten in Chinesisch-Turkistan; bericht über archäologische arbeiten von 1906 bis 1907 bei Kucǎ, Qarasǎhr und in der oase Turfan. Berlin: G. Reimer. - Hai, Willow Weilan and Jerome Silbergeld. 2013. Inspired by Dunhuang: Re-creation in Contemporary Chinese Art. New York: China Institute Gallery.

- Hatt, Robert T. 1980. ‘A Thirteenth Century Tibetan Reliquary: An Iconographic and Physical Analysis.’ Artibus Asiae 42: 175-220.

- Hopkirk, Peter. 1980. Foreign Devils on the Silk Road. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press.

- Huntington, Ellsworth. 1905-46. Archaeological specimens collected by Ellsworth Huntington in Chinese Turkestan – 1905, February 28, 1946, Series IV, Box 1, Folder 3, Ellsworth Huntington Papers, The Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

___ 1907. The Pulse of Asia. A Journey in Central Asia Illustrating the Geographic Basis of History. London, Boston, and New York: Houghton, Mif in & Co. - Klimburg-Salter, Deborah E. 1982. The Silk Route and the Diamond Path: Esoteric Buddhist Art on the Trans-Himalayan Trade Routes. Los Angeles: UCLA Art Council.

- Kuesntner. Molli E. and Thomas O’Callaghan. 2017. ‘The ‘Führerprojekt’ goes to Washington.’ The Burlington Magazine May 2017: 375-385.

- Kumagai Nobuo. 1954. ‘Kijiru dai san ku maya dō shōrai no hekiga – Shutoshite Doruna zō oyobi bunshari zu ni tsuite’ キジル第三区摩耶洞将来の壁画―主と して徒盧那像及び分舍利図について― [The Wall-paintings Brought from the Maya Cave of the Third Group at Qyzil]. Bijutsu kenkyū 美術研究 [Journal of Art Studies] 172: 19-33.

- Lee, Sonya S. 2015. ‘Central Asia Coming to the Museum: The Display of Kucha Mural Fragments in Interwar Germany and the United States.’ Journal of the History of Collections. Accessed February 4, 2016. doi: 10.1093/jhc/fhv031.

- Linrothe, Rob. 2014. Collecting Paradise: Buddhist Art of Kashmir and its Legacies. New York: Rubin Museum of Art.

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art. 1957. The Art of the T’ang Dynasty. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum.

- Ma De 马德. 1999. ‘Sancang Meiguo de wujian Dunhuang juanhua’ 散藏美国 的五件敦煌绢画 (Five Dunhuang silk paintings scattered in the collections in the United States). Dunhuang Yanjiu 1999-2 (60): 170-175.

- Mackie, Louise W. 2015. Symbols of Power: Luxury Textiles From Islamic Lands, 7th to 21st Century. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art.

- Mair, Victor. 1984. ‘The Complete Text of Śramaṇa Hui’s Subcommentary on the Quadripartite Prātimokṣa (Ssu-fen chieh-pen shu).’ Journal of the American Oriental Society 104(2): 327-332.

- March, Benjamin. 1928. ‘Buddhist Heads from Kizil.’ Bulletin of The Detroit Institute of Arts 10(1): 5-6.

- Matheson, Susan B. 2001. Art for Yale: a History of the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery.

- Meyer, Karl M. and Shareen B. Brysac. 2006. Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. New York: Persus Books Group.

- Morita, Miki. 2014. ‘Ksitigarbha Images from the Turfan region: An aspect of Uyghur Buddhist art of the 9th to 14th centuries.’ WEBSITE

___ 2015. ‘The Kizil Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum.’ The Metropolitan Museum Journal 50: 115-135. - Mote, Frederick. 1986. ‘The Oldest Chinese Book at Princeton.’ The Gest Library Journal 1(1): 34-44.

- Okuda Isao 奥田勲. 2000. ‘Kariforunia daigaku higashi Ajia toshokan zō kokyō korekushon mokuroku kō’ カリフォルニ ア大学東アジア図書館蔵古經コレクシ ョン目録稿 [Catalogue of the Old Sutra Collection in East Asian Library, University of California]. Seishin joshi daigaku daigaku ronsō 94: 109-171.

- Princeton University, the East Asian Library and the Gest Collection. ‘About the East Asian Library.’ (DOI 29/6/17). WEBSITE

- Proser, Adriana, ed. 2010. Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art. New York: Asia Society Museum.

- Pumpelly, Raphael. 1905. Explorations in Turkestan with an account of the Basin of Eastern Persia and Sistan. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

___ 1908. Explorations in Turkestan: Expedition of 1904: Prehistoric Civilizations of Anau: Origins, Growth, and Influence of Environment. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. - Reynolds, Valrae. 1999. From the Sacred Realm: Treasures of Tibetan Art from the Newark Museum. Munich: Prestel.

- Rong Xinjiang 荣新江. 2001. Dunhuang xue shiba jiang 敦煌学十八讲 (Eighteen lectures on Dunhuang). Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe. Trans. into English by Imre Galambos 2015 (Leiden: Brill).

- Russell-Smith, Lilla. 2005. Uygur Patronage in Dunhuang: Regional Art Centres on the Northern Silk Road in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. Leiden: Brill.

- Sasaguchi, Rei. 1972-73. ‘A Dated Painting From Tun-Huang In The Fogg Museum.’ Archives of Asian Art 26: 26-49.

- Schlingloff, Dieter. 2011. Albert von Le Coq und die Wandmalereien von Kizil (Addendum zu der Denkschrift: T III MQR, Eine ostturkistanische Klosterbibliothek und ihr Schicksal). Leipzig: private print.

- Seattle Art Museum. SAM Blog

- Sensabaugh, David Ake. 2014. ‘A Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Sutra at Yale.’ Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin Recent Acquisitions: 75-59.

- Sha Wutian 沙武田. 2009. ‘Yulinku di 25 ku bada pusa mantuluo tuxiang buyi.’ 榆林窟第25窟八大菩萨曼荼罗图 像补遗. Dunhuang yanjiu 敦煌研究5: 18–24.

- Sims-William, Ursula. 2012. ‘Huntington, Ellsworth.’ EI. WEBSITE

- Tomita, Kōjirō. ‘A Dated Buddhist Painting from Tun-Huang.’ Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 25, no. 152 (1927): 88-89.

- Ueno Aki 上野アキ. 1978. ‘Kijiru nihonjin dō no hekiga: Ru Kokku shūshū saiiki hekiga chōsa, 1’ キジル日本人洞の壁画: ル・コック収集西域壁画調査 1 [Mural paintings from Japaner Höhle in Kizil: Research on the mural paintings from the Western Regions collected by Le Coq, 1]. Bijutsu kenkyū 美術研究 [Journal of Art Studies] 308 (October):113–20.

___ 1980a. ‘Kijiru dai san ku maya dō hekiga seppō zujō: Ru Kokku shūshū saiiki hekiga chōsa, 2’ キジル第三区マヤ 洞壁画説法図—上: ル・コック収集西域 壁画調査 2 [Mural paintings of preaching scenes in Māyāhöhle, 3. Anlage, first part: Research on the mural paintings from the Western Regions collected by Le Coq, 2]. Bijutsu kenkyū 美術研究 [Journal of Art Studies] 312 (February): 48–61.

___1980b. ‘Kijiru dai san ku maya dō hekiga seppō zujō (zoku): Ru Kokku shūshū saiiki hekiga chōsa, 2” キジル第 三区マヤ洞壁画説法図—上 (続): ル・コ ック収集西域壁画調査 2 [Mural paintings of preaching scenes in Māyāhöhle, 3. Anlage, rst part (sequel): Research on the mural paintings from the Western Regions collected by Le Coq, 2]. Bijutsu kenkyū 美術研究 [Journal of Art Studies] 313: 91–97. - Van Schaik, Sam. 2000/2001. ‘Ellsworth Huntington and the Central Asian Manuscripts at Yale.’ IDP News 17: 4.

- Watt, James C. Y. and Anne E. Wardell. 1997. When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Waugh, Daniel and Ursula Sims-Williams. 2010. ‘Old Curiosity Shop in Khotan.’ The Silk Road 8: 69-96.

- Whitfield, Susan. 2002. Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries. London: The British Library.

- Whitfield, Susan, and Ursula Sims-Williams. 2004. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. London: The British Library.

- Wu, Tung 2003. Tales from the Land of Dragons: 1,000 years of Chinese Painting. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Yuyama, Akira and Hirohumi Toda. 1977. The Huntington fragment F of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra: introductory remarks by Akira Yuyama; texts transliterated by Hirofumi Toda. Tokyo: The Reiyukai Library.

Other Publications

The Ruins of Kocho: Traces of Wooden Architecture on the Ancient Silk Road

Lilla Russell-Smith and Ines Konczak-Nagel, eds. Berlin: SMB 2016

PB, 160 pp., €39.90

ISBN: 9783886097869

PUBLISHER’S WEBSITE

This book presents the results of a two-year project investigating the wooden architectural elements in the Turfan Collection and the three ruins in Kocho (Gaochang), and accompanied an exhibition at the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Kashgar Revisited: Uyghur Studies in Memory of Ambassador Gunnar Jarring.

Ildikó Bellér-Hann, Birgit N. Schlyter and Jun Sugawara, eds. Leiden: Brill 2016

HB, eBook, 338 pp., €116

ISBN: 9789004322974, 9789004330078

PUBLISHER’S WEBSITE

Orientalische Bibelhandschriften aus der Staatbibliothek zu Berlin — PK: Eine illustrierte Geschichte / Oriental Bibles from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin — PK: An Illustrated History

Meliné Pehlivanian, Christoph Rauch, Ronny Vollandt, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag 2016

HB, 186 pp., colour, b&w ill. €39.90

ISBN: 9783954902095

PUBLISHER’S WEBSITE

Silk Road Journal

Vol 14: 2016

The penultimate issue to be produced both in print and online.

WEBSITE

Medieval China

中古中國研究

Vol. 1: 2017

WESBITE

A new journal with articles in Chinese and English.

Conference Reports

From Khotan to Dunhuang: Case Studies of History and Art along the Silk Road

13-14 June 2017

Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, Hungary

Supported by Hanban (Confucius Institute Headquarters), this symposium was organised by ELTE’s newly established ‘One Belt, One Road’ Research Centre and the Silk Road Research Group of MTA–ELTE–SZTE.

The keynote speeches were given by Rong Xinjiang (Peking University) and Imre Galambos (University of Cambridge). Professor Rong presented results of his current Khotan and Dunhuang project, especially the research of Miraculous Images (瑞像) eg. in Dunhuang Cave 9. The ceiling of this cave shows eight guardian deities who seem to have a direct connection to Khotanese iconography.

Dr Galambos spoke about the production of religious manuscripts in Dunhuang, concentrating on manuscripts where the direction of the script is in vertical lines left to right (as opposed to right to left). This was followed by a session on Khotanese texts, with papers by Duan Qing and Fan Jingjing, both from Peking University. The afternoon session, on manuscripts, included presentations by Constantino Moretti (École Pratique des Hautes Études, Sorbonne, Paris), Gábor Kósa (ELTE), Saerji (Peking University) and Ágnes Birtalan (ELTE). The last session on this day was devoted to Manjusri and Huayan studies with papers from Chen Juxia (Dunhuang Academy) and Imre Hamar (ELTE).

The next day covered the art history with papers by Lilla Russell-Smith (Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), Beatrix Mecsi (ELTE), Meng Sihui (Palace Museum, Beijing), and Judit Bagi (Oriental Collection, Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest). A lively discussion closed the conference: new topics for future conferences and ideas for various collaborations were mentioned. The guests from China were then taken to see the famous reading room at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA), where Aurel Stein’s archive, books and photographic collections are kept.

Lilla Russell-Smith

Silk Road Forum 2017

2 April 2017 Princeton University

This public event, sponsored by Princeton University, Buddhist Studies Workshop, with the support of the Glorisun Foundation, consisted of two lectures, by Susan Whitfield (IDP) and Doucheng Du (Lanzhou University) with responses by Xin Yu (Fudan University) and Annette Juliano (Rutgers University).

WEBSITE

Buddhist Manuscript Cultures 2017

20–22 January 2017 Princeton University

This was the fourth and final event in a programme of public events organised at Princeton University by the Buddhist Studies Workshop and the Tang Center for East Asian Art. Major Funding was provided by the Henry Luce Foundation and others. For details, including abstracts of the papers, see the website.

The other events in the series were:

Conference 2014: ‘Prospects for the Study of Dunhuang Manuscripts: The Next 20 Years’, (6–8 September 2014): WEBSITE.

Symposium 2015: ‘Visualizing Dunhuang’ (13-14 November 2015)

Organized by the P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Center for East Asian Art with the Princeton University Art Museum, in conjunction with the exhibitions ‘Sacred Caves of the Silk Road: Ways of Knowing and Re-creating Dunhuang and Imagining Dunhuang: Artistic Renderings from the Lo Workshop’, held in the Art Museum, and the photography exhibition’ Dunhuang through the Lens of James and Lucy Lo’, held in the Department of Art and Archaeology at Princeton University.

WEBSITE

Conference 2016: ‘Buddhist Manuscript Cultures’ (15-17 January 2016)

WEBSITE

Forthcoming

Conference:

The Art and Archaeology of the Silk Road

11–13 October 2017

Portland State University, Portland, Oregon

WEBSITE

With keynote lectures by Daniel Waugh, Annette Juliano and Matthew Canepa.

Exhibition:

Asian Textiles: Art and Trade Along the Silk Road

16 December 2017 — 9 December 2018

Dallas Museum of Art

WEBSITE

Drawn from the DMA’s collection, this exhibition showcases fine examples of garments and ornamental hangings. The garments range from a Japanese reman’s coat to an Indian sari and a Chinese dragon robe. Asian Textiles highlights the passage of luxury goods along the Silk Road between eastern Asia, India and Central Asia.

Book:

Silk, Slaves and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road

Susan Whitfield

Oakland: University of California Press 2018.

PB and eBook, b/w and colour ills.

ISBN: 9780520281783

WEBSITE

This new books follows on from Life Along the Silk Road, but with each chapter telling the story of a different object, including earrings in a steppe burial, Kushan coins discovered in Ethiopia, a Hellenistic glass bowl found in China and a folio of the Blue Qur’an. Details will be available online in late summer.

IDP Field Trip to Kharakhoto

Rephotography or repeat photography consists of taking photographs at different points in times from the same physical vantage point. First developed in the 1880s as a way to monitor glaciers in Europe, it is a powerful tool for scientists and researchers working to track landscape and environmental variations.

Over the past decade, IDP has been using repeat photography to study the vicissitudes of time on some of the archaeological sites along the Silk Road that Aurel Stein explored and documented during his successive expeditions to Central Asia (see IDP News 32 and 39 and here). These visual records now constitute a significant photographic archive, part of the British Library collections.

In September 2016, six members of the IDP team at the British Library— including curatorial, conservation and photographic staff—went on a joint field trip with the Dunhuang Academy to Kharakhoto, with support from the Sino-British Fellowship Trust.

Following Stein’s footsteps on his third expedition, their journey took them to the Yulin caves and to Suoyangcheng ruins, over 100 km east of Dunhuang, before travelling north across the Gobi desert to reach the ancient Tangut city of Kharakhoto, which lies in Western Inner Mongolia on the Etsin-gol river.

It was here that Stein — following on from the Russian expeditions led by Kozlov — recovered many thousands of manuscript fragments, currently being conserved by IDP. Many of the fragments were found hidden in a Buddhist stupa outside the city walls. Little now remains of the stupa (pictured above right, photograph by Josef Konczak).

The new images taken by IDP echo those of Aurel Stein, over a century ago, and re ect the changes that have occurred in that lapse of time (such as the erection of a wind turbine just outside the city walls). The images are currently being processed and will all be available on IDP later this year. A selection will be shown in the next newsletter.

Mélodie Doumy, IDP Curator and Researcher

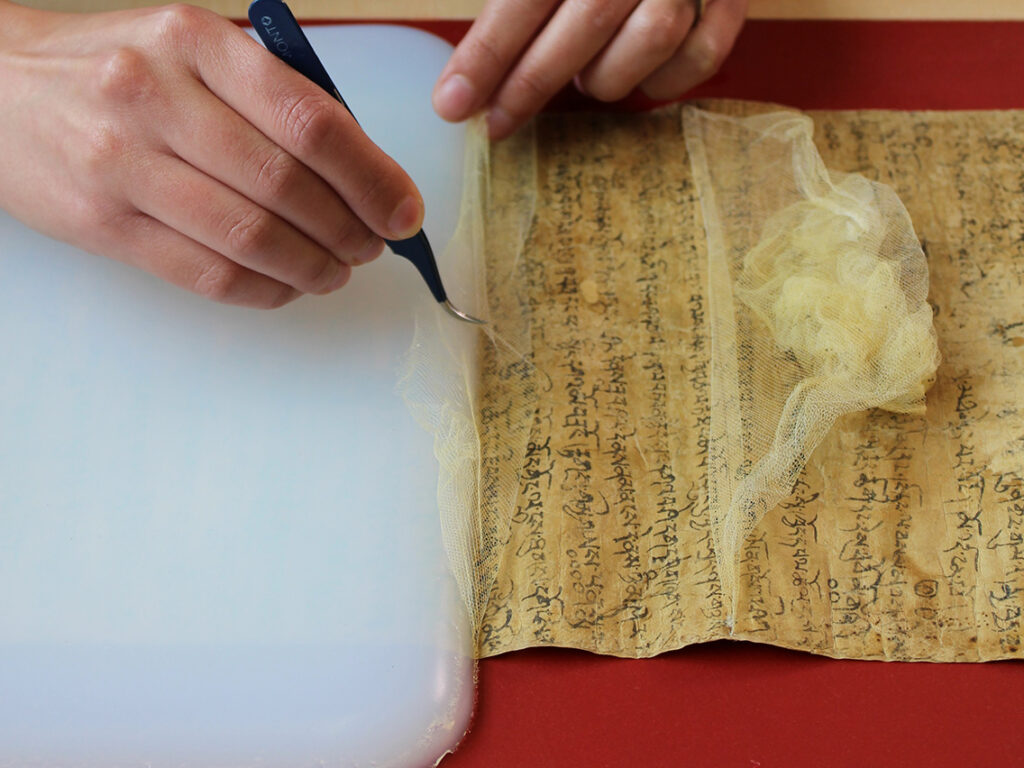

Conservation and Science

This image shows recent conservation treatment of a manuscript (Or.8210/S.155), using Agarose gel to remove an unsuitable silk gauze backing. The use of moisture would unsettle the yellow dye (huangbo 黄檗) and cause staining. By using a gel, the acidic animal glue adhesive on the gauze can be softened while staying dry, making removal possible.

This manuscript contains a copy of The Lotus Sutra in Chinese on one side with a Tibetan divination text on the other (pictured here). The conservation of the manuscript copies of the Lotus Sutra from Dunhuang is being carried out as part of a four-year IDP project generously funded by the Bei Shan Tang Foundation. The project also includes updating the catalogue records and digitisation of the manuscripts for inclusion on IDP.

Vania Assis, IDP Conservator

IDP Worldwide

IDP China

Dunhuang Academy

The Dunhuang Academy was involved in the Dunhuang International Cultural EXPO, held in Dunhuang from 20-21 September 2016. Zhang Xiantang and Susan Whitfield signed a renewal of the Memorandum of Understanding between their institutions during a signing ceremony. Wang Xudong, Director of the Dunhuang Academy, gave a very well-attended public lecture in London for IDP entitled ‘Dunhuang and Heritage Management.’ His visit was sponsored by the Sino-British Fellowship Trust.

The Dunhuang Academy mounted a joint exhibition in London with the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts, supported by the Dunhuang Culture Promotion Foundation. The exhibition, ‘Sacred Art of the Silk Road: Dunhuang’s Buddhist Cave Temples.’ was held from 16 May to 14 June 2017. It was accompanied with courses and lectures, including an IDP Conservation Open Day at the British Library.

National Library of China

In the summer of 2016, Ms. Zhao Qing, one of the two image manipulators, resigned from the IDP NLC Center. NLC employed Mr. Yuan Fang to replace Zhao Qing’s post and he started work in August 2016.

As of 17 May 2017, IDP NLC Center has completed digitisation of 4599 Dunhuang manuscripts, and has uploaded 163,135 images to the IDP Database.

Liu Bo gave a presentation at the ‘China Dunhuang-Turpan Society Council and International Symposium’ held in Jinan, Shandong on 29 October 2016.

One of China’s most important daily newspapers, Guangming Daily, published an article on 7 February 2017, ‘Even the Tiny Fragments have not been Abandoned’, giving a detailed report of the digital work of IDP NLC Centre. As seen in October 2016, when Liu Bo participated in the Jinan symposium, almost all of the Dunhuang manuscripts researchers are using images which IDP has digitized. The newspaper article and presentations by scholars thanked IDP for making these available showing that IDP is becoming more and more popular among Chinese scholars who are concerned with ancient literature, languages and history of China and Central Asia.

A team from IDP UK visited in September 2016.

IDP France

Nathalie Monnet, BnF, attended the two-day international conference on Buddhist Manuscript Cultures organized by Princeton University (20-22 January 2017). Her presentation was entitled ‘Towards a Reassessment of the Contents of the Dunhuang Cave 17.’

On 28 February 2017 Romain Lefebvre presented the paper ‘Did the Tanguts have their own medical treatments?’ at a workshop on Recent Advances in Tangut Studies, which took place at SOAS. This event brought together eight scholars to explore Tangut language, religion, and culture.

IDP Germany

A summer school ‘Sogdians and Turks on the Silk Road’ was held at the Berlin Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities from 2 August to September 2016. It was aimed at beginners in Central Asian studies. 46 international participants joined two language classes (Sogdian and Old Uyghur) and lectures on different topics each day. The research staff of the project ‘Turfan Studies’, and also those of the project ‘Union Catalogue of Oriental Manuscripts’ and researchers in Berlin gave the lectures. Various important topics dealing with Central Asia were covered. The Museum for Asian Art and the Museum for Islamic Art offered guided tours for the participants.

Lilla Russell-Smith of the Museum for Asian Art spoke at a Silk Road conference in Budapest. Her co-authored book The Ruins of Kocho, was also published.

Recent publications

Raschmann, S.-Ch. 2016. Alttürkische Handschriften Teil 20: Alttürkische Texte aus der Berliner Turfansammlung im Nachlass Resid Rahmeti Arat. Verzeichnis der Orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland, Band 13,28, Stuttgart.

Kasai, Y, 2017. Die altuigurischen Fragmente mit Brāhmī-Elementen. Berliner Turfan-texte XXXVIII, Turnhout.

Laut, J. P. and f J. Wilkens, 2017. Alttürkische Handschriften Teil 3: Die Handschriften-fragmente der Maitrisimit aus Sängim und Murtuk in der Berliner Turfansammlung. Verzeichnis der Orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland, Band 13,11, Stuttgart.

Hunter, E. and J.-F Coakley, 2017. A Syriac Service-Book from Turfan. Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin MIK III45. Berliner Turfantexte XXXIX, Turnhout.

Kasai, Y., S.-Ch. Raschmann, H. Wahlquist, and P. Zieme, 2017. The Old Uyghur Āgama fragments preserved in the Sven Hedin collection, Stockholm. Silk Road Studies 15, Turnhout.

IDP Japan

DARC (Digital Archive Research Center) could be adopted as a new branding project of Ryukoku University in appreciation of the achievement of the relationship with IDP. We are applying to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

On 30 June, a friendship research agreement between RCWBC (Research Center for World Buddhist Cultures) Ryukoku University and Lushun Museum was concluded at Fukakusa Campus.

IDP Russia

On 10 December 2016, Professors Du Jianlu and I. F. Popova held a ceremony for the presentation of 中国藏黑水城汉文文 献释录 [Chinese Language Documents from Kharakhoto in Chinese Collections]. The ceremony was held at Ningxia University in Yinchuan, China.

This 14-volume edition is the result of cooperation between the Russian Chinese Centre for Tangut Studies, IOM RAS, and the Chinese Russian Centre for Tangut studies, Ningxia University.

The Catalogue of Tangut Buddhist Texts Kept at the Institute of Oriental Studies, the Russian Academy of Sciences, by E. I. Kychanov with an introduction by Nishida Tatsuo , edited by Arakawa Shintaro (Kyoto University 1999) was made available as a downloadable pdf file.

On 14 June 2017, the third St. Petersburg Conference ‘Current Issues in Buddhological Studies’ was held at the IOM RAS.

IDP Sweden

The Swedish Research Institute (SRI) in Istanbul and the Asian Studies Centre, Bogacizi University jointly organised a conference entitled, ‘Rethinking Global Histories for the Present: The Overland and Maritime Silk Roads in Central Eurasia and the Indian Ocean’. Held at Bogacizi University, 28-30 April 2007, papers were given by Swedish participants, including Birgit Schylter, Hakan Wahlquist on Albert Hermann and Patrick Hallzon on the Kashgar Swedish missionary archives now in Sweden.

In addition, SRI hosted a reception to mark the publication of Kashgar Revisited.

Farewell from the IDP Director

In 1984, when I first visited Dunhuang and archaeological sites of northwestern China, I had no idea that these places would become a focus for much of my research and most of my future career. Over three decades later my fascination and enthusiasm for these places is unabated and l look forward to continuing to bring these collections and their history to a wider audience through writing, research and lecturing. But I am writing now to bid a sad farewell to my time as Director of IDP and Curator of the Central Asian Manuscripts at the British Library. This will be my final newsletter — I will be leaving at the end of July 2017.

My time at IDP has been enormously rewarding owing both to the collections and their history, but especially because of many people I have worked with over the years. The history of IDP has been told in previous newsletters, so I will not repeat it here, but I want to take this opportunity to thank the numerous people who have been supportive of IDP’s vision and for bearing with me as I tried to put this vision into place. Without all of you it would not have been possible. Working with a team of people with different skills and perceptions has been immensely rewarding and I have learned so much from everyone over the years.

For the 1990s, I must thank conservation, curatorial and management colleagues at the Library who, despite scepticism in these early years about my belief in the internet and presenting collections online, gave me the space and support to develop and implement these plans. Also in these early years the growing team of patrons were invaluable in guiding me around the potential quagmires of management and international collaborations. I was tremendously saddened by the death in 2016 of Abraham Lue, Chair of the Patrons and Steering Committee, who had been with IDP since the start. Without his support, belief and advice, IDP would not have happened.

Although I worked alone at the British Library secretariat for the first few years, we then raised funds to enable the growth of a small team: curators, conservators, IT and digitisation staff. Over the years the team has changed, and they are too many to mention here, but their names and achievements appear in earlier issues of this newsletter. I must also give thanks to them all.

Then, as the founder institutional members of IDP joined in making their collections available online, I worked with managers, curators, conservators and IT staff in institutions worldwide. Their belief, vision, hard work and dedication to their collections has also been vital to IDP’s success.

IDP is at a critical point. Well-established, respected and used by scholars and institutions worldwide, it now needs a major upgrade of its technical systems — database, CMS and website. This will provide much more efficiency and offer users more sophisticated and faster searches. A programme to implement this in Open Source software was planned to start in 2014. I am only sorry that my time assigned to manage this programme over the past few years has been spent instead on fighting for the future of IDP. I trust that, with the backing and involvement of patrons, partners, users and others, this programme can now be fully supported and completed without any further delay.

Before I leave I must thank you for all the time, effort and funding many of you have contributed over the years to make IDP the success it is today and, most especially, for your personal support and friendship. I very much hope that, having come so far thanks to the vision and support of all of you, IDP will continue to thrive so enabling this fantastic material to be preserved and made fully accessible to the growing numbers of interested scholars and others worldwide.

1984年第一次访问敦煌和中国西北 地区考古遗址的时候,我还没有意 识到这些地方将会成为我大部分研究 和未来职业生涯的关注点。三十年 后,我对这些地方的迷恋和热情有增 无减,我期待着继续通过写作、研究 和演讲,把那里出土的文物文献及其 历史带给更广泛的读者。但是我现在 正在写下一段悲伤的文字,与我作为 国际敦煌项目(IDP)主任和英国国 家图书馆中亚写本主管的时光告别。 这将是我的最后一份通讯——我将在 2017年7月底离开。

在IDP期间,我获益于中亚收集品 及其历史,尤其是多年来一起工作的 同事。之前的通讯中已经介绍过IDP 的发展历程,所以在这里我不再重 复,但是我想借此机会感谢一直支持 IDP愿景并和我一起将之付诸实施的 众多人士。如果没有你们,这是不可 能实现的。与技能和观念各不一样的 团队一起工作是非常有益的,多年来 我从每个人那里都学到了很多。

回首1990年代,我必须感谢英国国 家图书馆的保护、策划和管理等部门 的同事们,尽管最初几年他们对我的 互联网理念和在网络上公布写本表达 了怀疑,但他们给了我空间和支持来进行开发并实施这些计划。同样在最 初几年,不断扩大的赞助人队伍对我 处理潜在的管理和国际合作问题提供 了宝贵的指导。我对2016年劉鍚棠先 生(Abraham Lue)的去世感到非常 难过,他是赞助人和指导委员会的主 席,从一开始就始终支持IDP。如果 没有他的支持、信任和指导,IDP就 不会成立。

在最初的几年里,我独自在大英 图书馆的IDP秘书处工作。后来我们 筹集了资金,组建了一个小型团队, 包括管理、修复保护、IT和数字化工 作人员。多年来,这个团队经历了了 多次人事变动,有太多的人需要在这 里提及,他们的名字和成就已出现 在这份通讯的以前各期中。我也要感 谢他们。

然后,当IDP创始机构成员加入项 目合作,在网上公布各自藏品的时 候,我和世界各地的管理、策划、 保护修复和IT人员一起工作。他们的 信念、愿景、勤奋工作和对各自藏 品的奉献,对IDP的成功也是至关重 要的。

IDP正处于一个转折点。它结构完善,得到世界各地的学者和学术机构的尊重并被广泛使用,现在需要升级它的技术系统,即数据库、CMS和网 站。升级将大大提高工作效率,并为 用户提供更复杂、更快速的搜检索。 一个基于开源软件的升级计划原拟 在2014年启动。很遗憾的是,过去几 年我的时间主要在为IDP的未来而奋 斗。我相信,在赞助人、合作机构、 用户和其他人士的支持和参与下,这 项工作现在可以得到全力支持,不再 拖延,在短期内顺利完成。

因此,在我离开之前,我必须感 谢你们为IDP付出的所有时间、努力 和资金,你们在过去多年里的贡献让 IDP取得了今天的成功,我尤其感谢 你们个人的支持和友谊。我非常希 望,由于你们的远见和支持,IDP将 继续茁壮成长,让这些珍贵的文物文 献得到保护,并让越来越多的对其感 兴趣的学者和世界各地的人们能方便 地获取。

感谢中国国家图书馆刘波的翻译.

Thanks to Liu Bo of the National Library of China for his translation.

2011年敦煌研究院举办的国际敦煌项目工作会议中的国际敦煌项目成员。

IDP UK

Staff

Gethin Rees (pictured right) joined IDP in April 2017 in the role of GIS Research Curator. The post is funded by the ERC as part of the Beyond Boundaries synergy project. Gethin will be developing a map interface for the data produced by the Beyond Boundaries project, as well as working with Aurel Stein’s maps and archaeological plans.

We were very sad to say goodbye to Josef Konczak, IDP Studio Manager. We hope to have a replacement soon.

In October 2016, Mélodie Doumy went to Paris on a four-day trip to conduct research in the Papiers d’agents-archives privées of Charles Bonin that are held in the Archives du Ministère des Affaires Etrangères. She also looked at the Pelliot archives of the Guimet Museum’s Library and hopes to shortly write an article on Bonin, who visited the Dunhuang caves before Pelliot and Stein.

A team from IDP visited the National Library of China and the Dunhuang Academy in September 2016, before travelling on to Kharakhoto.

Sam van Schaik gave lectures at SOAS and the Courtauld Institute, University of London, the Victoria & Albert Museum. and the Centre for the Study of the Middle Ages at Birmingham, University. He also spoke at the Buddhist Manuscript Cultures conference at Princeton University (January 2017) and the Bonpo Manuscript Culture Workshop at the University of Hamburg (March 2017).

Susan Whitfield gave lectures at the Courtauld Institute of Art, the Victoria & Albert Museum, Christie’s and SOAS. She also presented papers at conferences at the National Silk Museum, Hangzhou, Durham University, at the Silk Road Forum at Princeton University (see p. 12) and at the conference held at Bogazici Universty, Istanbul (see p. 14). She participated in a UNESCO/ UCL international experts workshop on the serial nomination of the Maritime Silk Road at University College London (UCL) and in the Andrew W. Mellon-Sawyer Seminar ‘Cultural and Textual Exchanges: the Manuscript Across Pre-Modern Eurasia’ at The University of Iowa City (WEBSITE).

In May 2017 she was invited to join a group of artists, musicians, filmmakers, dancers and others for a visit to the Dunhuang Academy to discuss ideas for a long-term project initiated by Peter Sellars and inspired by the Vimalakīrtinirdeśasūtra. Peter Sellars had visited the Library in January 2017 to view manuscript copies of the sutra in preparation for the visit. These will be her final activities as IDP Director: she leaves the British Library at the end of July 2017.

Patrons

We are delighted that Professor Puay-peng Ho has accepted the invitation to become an IDP Patron. Puay-peng Ho is currently Professor of Architecture and head of Department of Architecture at National University of Singapore. He received architectural training at the University of Edinburgh and practiced as an architect in the United Kingdom and Singapore. He subsequently obtained his Ph.D. in architectural history from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. His research interests and publications are in Chinese architectural history, Buddhist art and architecture of East Asia, and architectural conservation. Before relocating to Singapore, Professor Ho taught in Hong Kong and served as advisor to the public museum system and chair of the Lord Wilson Heritage Trust in Hong Kong. He remains a member of Friends of Dunhuang Hong Kong and involved in advisory role with Dunhuang Research Institute. Professor Ho also conducted many conservation research and projects in rural and urban Hong Kong.

Tim Simon has tendered his resignation which we have accepted with regret. Tim has been involved in IDP since before the 2004 exhibition, first as a supporter and then as a patron.We have greatly valued his input over this period and are very sorry to see him leave. We thank him for his time and support over the years.

Conservation Open Day

IDP held a very successful Open Day on 8 June 2017 showcasing the work of conservators on different materials (including paper, textiles, and wood). The event was over subscribed and, despite the time-slots, many people stayed on to the next slot. This was organised as part of the activities around the PSTA exhibition (see below).

Exhibition at PSTA

An exhibition, ‘Sacred Art of the Silk Road, Dunhuang’s Buddhist Cave Temples’ was held from 16 May to 14 June 2017 at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts (PSTA) in London (WEBSITE).

Organised by the PSTA with the Dunhuang Culture Promotion Foundation and the Dunhuang Academy, the exhibition displayed a copy of a cave from Dunhuang along with paintings and manuscripts. The British Library and British Museum provided images of several manuscripts so that facsimiles could be made for exhibit. A programme of courses and lectures accompanied the exhibition.

Funding

We were delighted to receive support from the Bei Shan Tang Foundation for a four-year project to conserve, digitise and make available on IDP copies of the Lotus Sutra from Dunhuang. Conservation work for the project has already started and we hope to start digitisation very shortly.

Download this newsletter as a PDF

This digital version of IDP News is based on the print version of the newsletter and some links and content may be out of date.

This issue, No. 49-50, was published Summer 2017.

Editor: Susan Whitfield

ISSN 1354-5914

All text and images copyright their creators or IDP, except where noted. For further information on IDP copyright and fair use, please visit our Copyright page.

For further information about IDP please contact us at [email protected] or visit our Contact page.