IDP Collections in Britain

This summary of the history and make-up of the collections held in British institutions was produced by the IDP team, led by Susan Whitfield, in December 2005. The information was last updated in November 2010. While we are keeping this text up as a background resource, please be aware that new information may have come to light since its initial writing.

British Explorations in Chinese Central Asia

British Explorations in Chinese Central Asia

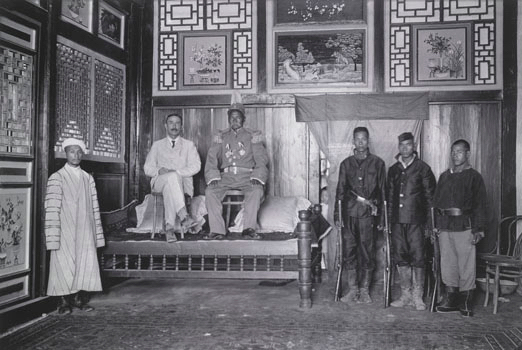

unknown © British Library

British explorations in Central Asia started in the wake of the 19th-century Great Game, when Britain and Russia had vied for political control of this arena. With the then-British empire in India and the Russian empire controlling the Central Asian steppes, each wished to prevent the other graining control and intelligence about the land between. Throughout the 19th century spies were sent to gather intelligence and draw maps, often at personal risk. But towards the end of the century interest expanded to include the region’s geography, flora and fauna.

The British in India used locals as spies and surveyors, the first such official ‘pundit’ being Mohamed-i-Hameed. He reached the Taklamakan in 1863 and, in his report, wrote of sand-buried ancient cities. He died on his way back and the British surveyor William Johnson, who investigated his death, embarked on his own journey in 1865. He visited one such ruin near Khotan and wrote in his report that he believed there were many more. This in turn prompted the interest of Thomas Douglas Forsyth who in 1870 was sent to visit the short-lived ruler of an independent Chinese Turkestan, Yakub Beg. Yakub Beg proved to be absent and elusive and so Forsyth went on a repeat mission three years later. His presentation to the Royal Geographical Society told of more of these buried cities and the artefacts uncovered from them, including a figure of Buddha which he later had dated to the tenth century. The published report (Forsyth, 1875) contains early photographs of the area (OIOC Photo 997).

In 1889 local treasure hunters found a cache of manuscripts in a site south of Kucha on the northern Silk Road and subsequently sold some to a local scholar, Haji Ghulam Qadir. In turn, one was purchased from him by an Indian Army intelligence officer, Lieutenant Bower, who sent the fifty-one folios of birch bark in an unknown language to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Here it was studied by A. F. R. (Rudolph) Hoernle, Principal of Calcutta Madrassah and a respected scholar of Indo-Aryan languages. Hoernle soon realised the importance of this manuscript, which contained several Buddhist texts in Sanskrit, and he subsequently wrote that its discovery and publication ‘started the whole modern movement of the archaeological exploration of Eastern Turkestan.’

From 1893, at Hoernle’s instigation, the Political Officers in Gilgit, Chitral, Kashgar and Leh were instructed to obtain whatever manuscripts they could find and send them to Hoernle to be deciphered. These formed what became known as the Hoernle Collection, or the British Collection of Antiquities from Central Asia, now in the British Library. By 1899, when Hoernle published the first part of his report on the collection (Hoernle, 1899), it included over 500 coins, numerous seals, terracottas, in addition to more than 100 substantial fragments of manuscripts in various known scripts and languages as well as two unknown languages: Khotanese and Tocharian. The collection also, however, included manuscripts and woodblock prints in unrecognisable scripts. These had all been sent to him in Calcutta by George Macartney, British representative in Kashgar and Stuart Godfrey, Assistant to the Resident in Kashmir.

George Macartney and Early Forgeries

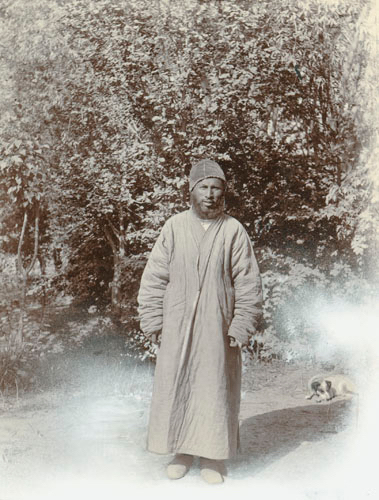

Frederick M. Bailey © British Library

In 1890 an expedition led by Francis Younghusband and sponsored by the British government to establish a base in Chinese Central Asia arrived in Kashgar. Younghusband negotiated with the Chinese authorities to establish a British Consul there but they initially refused and in 1891 the expedition departed, all except the young Scottish-Chinese translator, George Macartney. He was left behind to act as an unofficial representative. He had a Russian counterpart, Mr Petrovski, who had been in Kashgar since 1882 and was granted the status of Consul. Macartney had to wait until 1909.

M. Aurel Stein © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Stein Photo 3/6(19)

In 1896 Macartney was approached by a Khotanese man called Islam Akhun who offered him manuscript finds purportedly from ancient sites in the desert. He purchased these and sent them to India where Hoernle started work on trying to decipher the unknown script — which at first sight resembled Indian Brahmi — and the language. Hoernle included some in his preliminary report in 1897 and gave a full report in 1899. In the latter he considered whether the manuscripts were forged but dismissed the idea, although he could not understand them. However, others were not convinced. In April 1901, Stein tracked down Islam Akhun in Khotan and questioned him closely. Islam Akhun finally admitted that he and colleagues had made these ‘old books’ themselves. Stein broke the news to Hoernle (by then retired) on his return to Britain.

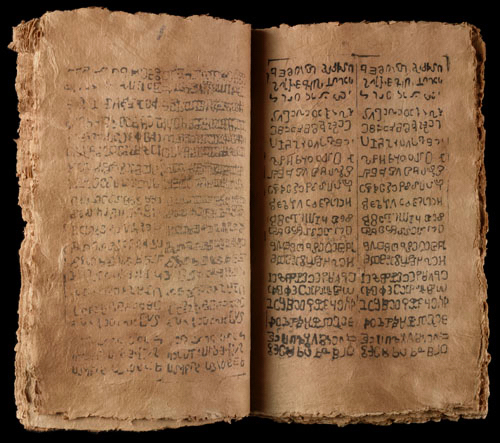

IDP © British Library Or.13873/2

Fortunately, Stein returned with further manuscripts in another then-unknown language (Khotanese), which Hoernle subsequently deciphered, so scholarly honour was salvaged. The forged manuscripts and blockprints are preserved in the British Library collection (Or.13873 and Or.13873/58). A project site on forgeries will go live in 2006.

Macartney continued at Kashgar until 1918 and during his time acquired other manuscripts and finds, the greater part sold to him by locals. Most of these are now in the British Library and British Museum collections (see below). Succeeding Consuls, such as George Sherriff, Frederick Williamson and Sir Clarmont Skrine also obtained manuscripts and artefacts. Sir Percy Sykes also kept a photographic record.

Marc Aurel Stein (1862-1943)

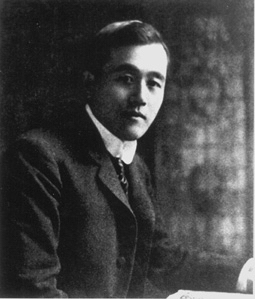

Aurel Stein © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Stein Photo 3/6(2)

The publication of the Bower manuscript (Hoernle, 1893), news of Islam Akhun’s finds and reports of the Swedish explorer, Sven Hedin, prompted a Hungarian, Marc Aurel Stein, to arrange a expedition to Chinese Central Asia in 1900. Stein, an Indo-Iranian scholar, had been working in Lahore in British India since 1887 and soon after applied for British nationality. In 1898 he moved to Calcutta to succeed Hoernle, on this scholar’s recommendation (although he returned to Lahore after only a year). Between 1900 and 1930 he carried out four expeditions to Chinese Central Asia, conducting excavations along the whole of the Southern Silk Road, at Dunhuang and Turfan, as well as surveying, photographing and enthnographical surveys.

Born in Hungary in 1862, Stein had studied Persian and Sanskrit in Austria and Germany and had then studied and worked in England and India, all in pursuit of his ultimate goal to explore the old trade routes of Central Asia. He had read about the campaigns of Alexander the Great as a child, and later of Xuanzang’s and Marco Polo’s travels. He was particularly interested in the meeting of cultures — Iranian, Indian, Turkic, and Chinese — along the Southern Silk Road.

In the eleven months of his first expedition (1900–01), Stein concentrated on the sites of Khotan, Niya, Miran and Loulan. He published a full expedition report (Stein, 1907) and a more popular account of his travels (Stein, 1903), along with several papers (see bibliography).

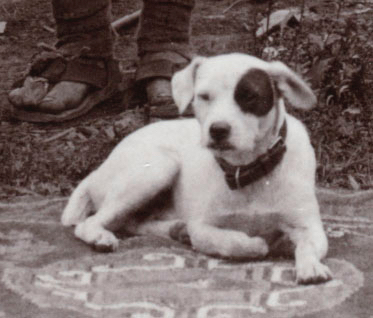

M. Aurel Stein © British Library Photo 392/27(376)

Stein’s second expedition (1906–8) took him back to previously-visited and new sites of the southern Silk Road where he carried out further excavations, before moving eastwards to Dunhuang in order to study and excavate at the Han-dynasty defenses to the north of the town. He then visited the Mogao cave site southeast of the town, where he acquired material from the Library Cave. He travelled on to the northern Silk Road, stopping briefly at Turfan sites but not carrying out any excavations. He made a perilous north-south crossing of the Taklamakan in order to make time to excavate at more ruins near Khotan, and finished off his expedition with surveying in the Kunlun Mountains. Here he lost his favourite pony to exhaustion and some of his toes to frostbite. A popular account followed a few years later (Stein, 1912) but the full expedition report in five volumes, complete with maps and plates (Stein, 1921) took several more years to complete (see bibliography).

M. Aurel Stein © British Library Photo 392/29(10)

The third expedition was even longer, lasting from 1913 to 1916 and taking Stein back to the southern Silk Road sites, to Dunhuang and further east, and thence to excavations at sites near Turfan on the northern Silk Road, especially Astana and Bezeklik. He travelled to Kashgar along the northern route but then, rather than return directly to India, he crossed the Pamirs, followed the Afghan border and then moved to Sistan in western Iran where he carried out further excavations. Although he published a full report of this expedition some years later (Innermost Asia), he did not publish a popular account of this expedition but, in 1933, produced an account of his all three expeditions.

Although Stein managed to cover two thousand miles on his fourth expedition (1930-1) and revisit many favourite sites, the expedition was cut short as Stein heard of plans to confiscate his passport. His few finds were taken by the authorities in Kashgar and this was Stein’s last visit to Chinese Central Asia. He undertook four expeditions to Iran and Iraq in the succeeding years, carried out aerial surveys of Roman defences in the Near East, followed Alexander the Great’s footsteps in Central Asia and finally died in Kabul planning a year-long archaeological tour of Afghanistan.

IDP ©

Stein’s original material was divided between London (the British Museum, the India Office Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum) and India, whose government had also provided sponsorship for his first three expeditions. By 1982, the majority of the London manuscripts and photographs had been transferred to the British Library, where they remain, with the British Museum housing the collections of paintings, sculptures, coins and other artefacts. The Victoria and Albert Museum holds textiles.

The murals, paintings, artefacts and manuscripts sent to India are now mainly in the National Museum, New Delhi. There are smaller collections from the first expedition in the Indian Museum, Calcutta and in Pakistan in the Oriental Museum, Lahore.

Stein’s papers, including his expedition diaries, letters, account books etc. are largely housed in the Western Manuscript Department of the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

For details of other collections of Stein material in the UK, see The Handbook to the Stein Collections in the UK, produced by Helen Wang of the British Museum (Wang 1999). This will shortly be available online.

The collections of Sir Aurel Stein in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, include many photographs, personal papers, some of his finds, and his library, have been catalogued (Apor, 2002 and Apor, 2007).

Collections: Contents and Access

Britain holds a collection of about 50,000 manuscripts, paintings and artefacts from Chinese Central Asia, as well as thousands of historical photographs, mostly coming from the first three Central Asian expeditions of Aurel Stein. A large proportion of Stein’s finds from his second and third expedition are held in the National Museum of India, New Delhi. The Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest hold many of Stein’s expedition photographers, personal papers and some manuscripts. The Bodleian Library, Oxford, has a large collection of Stein papers. The British Library has papers relating to Macartney, Hoernle, Stein and the British in Central Asia. There are other smaller collections in several other UK institutions.

1. The British Library

1.1 The Stein Collection

IDP ©

The British Library Stein collection contains over 45,000 manuscripts and printed documents on paper, wood and other materials in many languages, including Chinese, Tibetan, Sanskrit, Tangut, Khotanese, Kuchean, Sogdian, Uighur, Turkic and Mongolian. Some of the manuscripts contain more than one language; some are indecipherable. The collection also includes a few paintings on hemp and paper, a small collection of textile fragments, and artefacts such as sutra wrappers, paper cuts and paste brushes, along with over 10,000 prints, negatives and lantern slides taken by Stein in India, Pakistan, Chinese Central Asia, Iran, Iraq and Jordan, dating from the 1890s to 1938.

1.2 Other Central Asian Collections

Apart from the Stein collection, the British Library includes Central Asian manuscripts collected by the Government of India, usually referred to as the Hoernle Collection. These include 22 consignments sent to Hoernle to decipher in Calcutta between 1895 and 1899. They were eventually deposited in the British Museum in 1902 after publication of his Report (1899 and 1901). 10 further consignments (numbered 142–44, 147–52, and 156) continued to be collected for him after his retirement in 1899 and were forwarded to him in England for examination. Altogether the Hoernle collection contains over 2000 Sanskrit, 1200 Tocharian and about 250 Khotanese items in addition to a few in Chinese, Persian and Uighur.

Hoernle died in 1918, but the Government of India continued to collect manuscripts and artefacts albeit on a smaller scale. Several small but important collections were transferred to the British Museum by Macartney’s successors at Kashgar, namely Nicholas Fitzmaurice, George Sherriff, Frederick Williamson, and Clarmont Skrine.

Skrine’s photographs (OIOC Photo 920) and papers are also in the British Library. Photographs from Central Asia in APAC European Private Papers can be found in the online photograph catalogue, and papers in the online private papers catalogue, both available as part of the BL’s India Office Materials.. There are also relevant papers and documents in the Western manuscripts and the IOL manuscripts and records departments at the British Library.

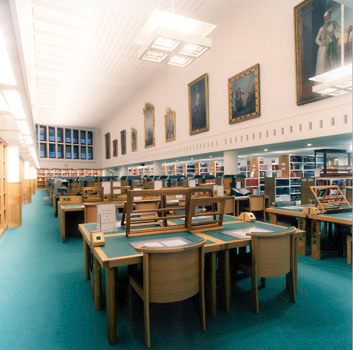

1.3 Access to British Library Collections

The British Library © British Library

A few selected items from the British Library manuscript collections are on display in the John Ritblat Gallery which is free and open all week. These items are changed regularly to avoid over exposure to light. In addition, the printed Diamond Sutra is available in digital form on the ‘Turning the Pages’ computer screens in the same gallery, on CD and online as a Virtual Book. There are many catalogues (see bibliography) and most of the manuscripts have been microfilmed. The non-Buddhist Dunhuang Chinese manuscripts have been published in 14 facsimile volumes by Sichuan People’s Publishers. In order to protect the originals which will suffer from too much handling, scholars are expected to consult the microfilms, facsimiles or digital images first. If still necessary, manuscripts are accessible to scholars on request in the APAC Reading Room, but the relevant curator must be contacted well in advance of your visit. Some manuscripts are too fragile to be viewed and the curator has to check all manuscripts in advance. If you do not give sufficient notice then it might not be possible to see the manuscripts.

The British Library © British Library

To get access to the APAC Reading Room you will first need a readers’ ticket (click here for details).

Click here to get full details on access to Stein manuscripts.

The photographs are available for viewing in the Prints and Drawings Reading Room by appointment only and also searchable on the APAC photographic database (although this has no images at present).

Click here to get details of the British Library location and opening hours.

2. The British Museum

2.1 Stein Collection

The Silk Road Exhibition Cat No. 178, page 241. © 1919,0101,0.47

The British Museum Stein collection from Chinese Central Asia consists of almost 400 paintings from Dunhuang, some textiles, several thousand artefacts from various sites, including architectural features, terracotta sculptures, and over four thousand coins. The Museum also holds a collection of Stein material from his expeditions to Iran and Iraq.

2.1 Access to British Museum Collections

The Stein collection of material from Chinese Central Asia on permanent display in the Hotung Gallery in the Museum consists of four cases containing a selection of archaeological finds by Stein. No paintings, works on paper, or textiles are on display because of light coming through the windows on both sides of the Hotung Gallery. These, however, can be seen by arrangement in the Study Room where there are registration cards available of every object in the Stein collection and visitors are entitled to look through these cards and then ask for objects not on view in the Gallery to be brought to them at a specified time in the Study room (which could be a day or two hence, depending on availability of the Museum Assistants).

Viewing of the Dunhuang paintings, which are on screens in the Stein room and cannot be removed, needs to be by prior arrangement with curators and Museum Assistants. Most of the paintings and artefacts have been reproduced in three volumes, (Whitfield 1982-5). High quality digital images of the paintings and a selection of artefacts are accessible on screens in the Study Room and on the British Museum website. Contact the Department of Asia for further details.

The British Museum ©

A few of the coins collected by Stein are on permanent display in the Money Gallery (gallery 68). Those not on display are housed in the Department of Coins and Medals – they are available to visitors in the departmental Study Room by appointment. Initial lists of the coins are found in the Appendices to Stein’s three major reports. For a revised and more detailed study of the coins, see Wang 2004.

Click here for information about the department of coins and medals.

Click here to get details of the British Museum location and opening hours.

3. The Victoria and Albert Museum

3.1 Stein Collections

A few items are on display in the public galleries and the rest are available for study by prior arrangements with the curators. Many are also accessible on the V&A Stein Collection page.

Click here to for contacts at the museum.

Click here for details of the V&A location and opening hours.

4. Other Stein Collections

Go to further information on the Stein Collections in the National Museum, New Delhi.

For further details of Stein collections in the UK see Wang 1999 (shortly to be available online).

5. Other Central Asian Collections in the UK

The following libraries in the UK contain archival and photographic collections of Central Asian travellers, in addition to the working papers of scholars who have worked in the area:

Collections: On IDP

The British Library, British Museum and V&A collections are all being digitised as part of IDP.

1. The British Library

As of the end of 2008, over 100,000 images representing over 20,000 items from the British Library were available online. It is planned that 80% of the material will be available by 2013 subject to funding. A summary is given below showing the breakdown by language.

Number of Manuscripts by Language/Script on IDP in the UK as of 08/09/2023

| Language(s)/Script(s) | Number of manuscripts/blockprints | Number Digitised |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Phags-pa (script) | 2 | 2 |

| Arabic (lang.) | 2 | 2 |

| Arabic (script) | 2 | 2 |

| Avestan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Avestan (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Bactrian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Brahmi (script) | 11,778 | 11,603 |

| Chinese (lang.) | 21,313 | 14,123 |

| Chinese (script) | 21,312 | 14,122 |

| East Syriac Maḏnḥāyā (Nestorian) (script) | 0 | 0 |

| English (lang.) | 171 | 146 |

| forged | 24 | 24 |

| French (lang.) | 9 | 9 |

| Gandhari Prakrit (lang.) | 410 | 355 |

| German (lang.) | 1 | 1 |

| Greek (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Greek (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Gupta (script) | 9 | 6 |

| Hebrew (script) | 1 | 1 |

| Hepthalite (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Judaeo-Persian (lang.) | 1 | 1 |

| Kharosthi (script) | 429 | 374 |

| Khitan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Khitan large (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Khotanese (lang.) | 2,364 | 2,312 |

| Kok Turkic (script) | 13 | 12 |

| Latin (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Manichaean (script) | 10 | 9 |

| Middle Persian (lang.) | 6 | 4 |

| Mongolian (lang.) | 17 | 10 |

| Mongolian (script) | 15 | 8 |

| Nagari (script) | 0 | 0 |

| New Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| not applicable | 77 | 67 |

| Old Turkic (lang.) | 114 | 30 |

| Pahlavi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Pala (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Parthian (lang.) | 5 | 5 |

| Sanskrit (lang.) | 8,737 | 8,648 |

| Siddham (script) | 3 | 2 |

| Sogdian (lang.) | 95 | 64 |

| Sogdian (script) | 74 | 50 |

| Syriac (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tangut (lang.) | 4,233 | 3,615 |

| Tangut (script) | 4,225 | 3,606 |

| Tibetan (lang.) | 7,055 | 4,252 |

| Tibetan (script) | 7,067 | 4,264 |

| Tocharian A (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian B (lang.) | 1,268 | 1,262 |

| Tocharian C (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tumshuqese (lang.) | 5 | 5 |

| unidentified (lang.) | 254 | 227 |

| unknown (script) | 2 | 1 |

| Uyghur (script) | 308 | 180 |

| Zhang-zhung (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Total* | 47,188 | 36,191 |

In addition, eight thousand Stein photographs have already been digitised.

2. The British Museum

Almost all the British Museum Stein paintings are now online, along with a selection of artefacts. Funds are being sought to digitise the remainder of these. The coin collection is not currently part of IDP although discussions are underway.

3. The V&A

All the 700 V&A textiles are now online on IDP.

4. Other Collections

The Stein photographs from the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences are being digitised and made available online.

IDP is currently in discussion with the National Museum, New Delhi about starting a programme of digitisation.

Bibliography

Andrews, Fred. H., Stein, Aurel, Ancient Chinese Figured Silks Excavated by Sir Aurel Stein at Ruined Sites of Central Asia. London: Bernard Quaritch, 1920.

Andrews, Fred. H., Stein, Aurel, Ancient Chinese Figured Silks Excavated by Sir Aurel Stein at Ruined Sites of Central Asia. London: Bernard Quaritch, 1920.

Apor, Eva (ed.), Wang, Helen (ed.), Falconer, John, Karteszi, Agnes, Kelecsenyi, Agnes, Russell-Smith, Lilla, Supplement to the Catalogue of the Collections of Sir Aurel Stein in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Budapest: Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2007.

Bailey, H. W., Khotanese Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1945-1963.

Bailey, Harold W. (ed.), Emmerick, R. E. (ed.), Saka Documents. London: Percy Lund Humphries, 1960.

Bailey, Harold W. (ed.), Saka Documents III. London: Percy Lund, Humphries, 1964.

Bailey, Harold W., Saka Documents: Text Volume. London: Percy Lund, Humphries, 1968.

Barnett, L. D., ‘Preliminary Notice of the Tibetan Manuscripts in the Stein Collection’. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1903): 109-114.

Dabbs, Jack A., History of the Discovery and Exploration of Chinese Turkestan. The Hague: Mouton, 1963.

Deasy, Captain H. H. P.l, In Tibet and Chinese Turkestan. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1901.

Giles, Lionel, Report of a Mission to Yarkhund in 1873, Under Command of Sir T. D. Forsyth, with Historical and Geographical Information Regarding the Possessions of the Ameer of Yarkhund. Calcutta: Foreign Dept. Press, 1875.

Giles, Lionel, ‘Chinese Inscriptions and Records’. In Stein, A., Innermost Asia: Detailed Reports of Explorations in Central Asia, Kan-su and Eastern Iran. Vols 1-4. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 1981.

Grinstead, Eric, Title Index to the Descriptive Catalogue of Chinese Manuscripts from Tunhuang in the British Museum. London: The British Museum, 1963.

Hartmann, Jens-Uwe, Wille, Klaus, ‘Die nordturkistanischen Sanskrit-Handschriften der Sammlung Hoernle’. In Sanskrit-Texte aus dem buddhistischen Kanon: Neuentdeckungen und Neueditionen. Göttingen: Vandebhoeck & Ruprecht, 1992.

Hoernle, A. F. R., ‘Three Further Collections of Ancient Manuscripts from Central Asia’. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 66 (1897): 213-60.

Hoernle, A. F. Rudolf, Facsimile Reproduction of Weber Mss., part IX and Macartney Mss., set 1 with Roman Transliteration. Calcutta: , 1902.

Hopkirk, Peter, Foreign Devils of the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. London: John Murray, 1980.

Macdonald, Ariane, Imaeda, Yoshiro, Choix de documents tibétains conservés à la Bibliothèque nationale complété par quelques manuscrits de l’India Office et du British Museum. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, 1978.

Maspero, Henri, Les Documents Chinois de la Troisieme Expedition de Sir Aurel Stein en Asie Centrale. London: The Trustees of the British Museum, 1953.

Michaelson, Carol, Gilded Dragons. buried Treasures from China’s Golden Ages. London: British Museum Press, 1999.

Rong, Xinjiang, ‘The historical importance of the Chinese fragments from Dunhuang in the British Library’. British Library Journal 24. 1 (Spring 1998): 78-89.

Sims-Williams, Nicholas, ‘The Sogdian Fragments of the British Library’. Indo-Iranian Journal 18 (1976): 43-82.

Stein, M. Aurel, Preliminary report on a journey of archæological and topographical exploration in Chinese Turkestan. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1901.

Stein, M. Aurel, Sand-buried ruins of Khotan; personal narrative of a journey of archaeological and geographical exploration in Chinese Turkestan. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1903.

Stein, M. Aurel, Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal Narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China. London: Macmillan, 1912.

Stein, M. Aurel, Guide to an exhibition of paintings, manuscripts and other archaeological objects collected by Sir Aurel Stein in Chinese Turkestan. London: British Museum, 1914.

Stein, M. Aurel, On Ancient Central-Asian tracks: brief narrative of three expeditions in innermost Asia and north-western China. London: Macmillan & Co., 1933.

Takeuchi Tsuguhito, Old Tibetan Manuscripts from East Turkestan in the Stein Collection of the British Library. Tokyo: The Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies for Unesco, The Toyo Bunko & The British Library Board, 1997.

Takeuchi Tsuguhito, Old Tibetan Manuscripts from East Turkestan in the Stein Collection of the British Library. Tokyo and London: Centre for East Asia Cultural Studies for UNESCO and the British Library, 1997-98.

Thomas, F. W., Tibetan literary texts and documents concerning Chinese Turkestan. London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1935-63.

Waley, Arthur, A Catalogue of Paintings Recovered from Tunhuang by Sir Aurel Stein. London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1931.

Walker, Annabel, Aurel Stein: Pioneer of the Silk Road. London: John Murray, 1995.

Wang, Helen, ‘Catalogue of the Sir Aurel Stein Papers in the British Museum Central Archives’. In Wang, Helen (ed.), Sir Aurel Stein, Proceedings of the British Museum Study Day, 23 March 2002. London: British Museum Occasional Paper 142, 2004.

Whitfield, Roderick, ‘Buddhist Paintings from Dunhuang in the Aurel Stein Collections’. Orientations 14. 3 (1983): 14-28.

Whitfield, Roderick, The Art of Central Asia: The Stein Collection in the British Museum. Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd, 1982-5.

Whitfield, Roderick, ‘Four unpublished paintings from Dunhuang in the Oriental collections of the British Library’. The British Library Journal 24. 1 (1998): 90-97.

Whitfield, Roderick, ‘Indian connections in the art of Dunhuang: the silk painting of Famous Images in the Stein Collection, London and New Delhi’. In Zamponi, Lindsay (ed.), Desző, Csaba (ed.), Ghose, Madhuvanti (ed.), Russell-Smith, Lilla (ed.), ‘The South Asian Legacy of Sir Aurel Stein’ (forthcoming).

If you have feedback or ideas about this post, contact us, sign in or register an account to leave a comment below