IDP Collections in France

This summary of the history and make-up of the collections held in French institutions was produced by the IDP team, led by Susan Whitfield, in December 2005. The information was last updated in November 2010. While we are keeping this text up as a background resource, please be aware that new information may have come to light since its initial writing.

French Explorations in Central Asia

French Explorations in Central Asia

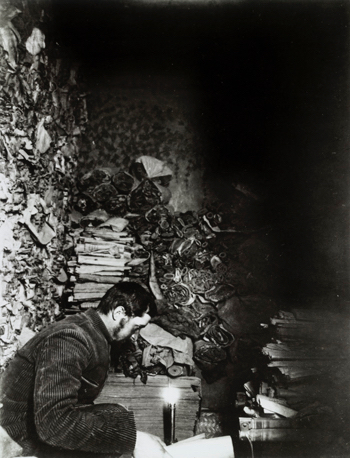

M. Aurel Stein © British Library Photo 392/28(620)

During the 19th century, France mounted a growing number of expeditions to the various regions of Asia, from Vietnam to the Himalayas. These expeditions began as largely geographical and scientific explorations, forging new routes in uncharted territory and collecting botanical and geological samples. The travelers faced many hardships, including illness, freezing temperatures and hostility from some locals, including bandits. As the century progressed, the expeditions became increasingly multi-disciplinary and widened their focus to include the cultural dimensions of current and previous civilizations. A huge quantity of findings were regularly sent back to Paris for research, thereby expanding and consolidating the growing body of knowledge in botany, geology, topography, cartography, ethnography, archaeology and linguistics. These explorers (some of whom are mentioned in the next few paragraphs) paved the way for the Silk Road excavations by Paul Pelliot and others at the turn of the 20th century.

The 19th century explorers included geologist and natural scientist Victor Jacquemont (1801–32), the first Frenchman to travel extensively in India under British rule. From 1828 until his death in Bombay in 1832, Jacquemont traversed the entire sub-continent, including the remoter parts of the Himalayas. He recorded in detail the flora, fauna and climate of the regions he visited; discovered several new species of plant and mammal; and his correspondence and posthumous publications were highly influential in the scientific community in France.

In the 1840s, Christian (Catholic) missionaries Évariste Huc (1813–60) and Joseph Gabet (1808–53) entered Mongolia and Tibet, disguised as lamas, and in 1846 they reached the Tibetan capital Lhasa, then regarded as off limits to foreigners. Huc was a Chinese speaker who had studied Buddhism. He made few notes during his demanding voyages but subsequently wrote several volumes which achieved great popular success in France and beyond.

Before the end of the nineteenth century, Gabriel Bonvalot (1853–1933) and his sponsor the Prince of Orléans had made the formidable journey to Hanoi through Chinese Turkestan and Tibet (1889–91), making topographical and zoological observations. Jules Dutreuil de Rhins (1846–1894) had mapped Vietnam and, with Fernand Grenard (1866–?), had traveled (1890–94) difficult and often new routes through Khotan, Chinese Turkestan, Mongolia and Tibet. De Rhins was murdered in Tibet in 1894 but Grenard returned with a spectacular collection of geological and archaeological specimens, photographs and maps, as well as astrological, barometric and other data which Grenard subsequently published extensively.

By the turn of the 20th century, the French stood alongside the English, Russians, Germans and Americans: all were vying for influence in Asia. In 1900, the Boxer rebellion against western and Christian influence drew foreign troops, journalists and adventurers to Peking. Among them was the young French fighter Paul Pelliot who was to return as a scholar only four years later.

Paul Pelliot Expedition

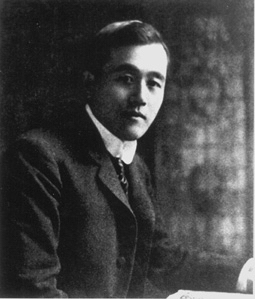

© Guimet Museum

1901 saw the establishment in Vietnam of the École Française d’Extrème Orient (EFEO), to research the region’s archaeological and linguistic heritage. Sinologist Paul Pelliot (1878–1945) was on the staff and, in 1905, he was chosen by French politicians and scholars to lead an expedition to the Kucha oasis and Dunhuang.

Pelliot spoke fluent Chinese and several regional languages and took responsibility for the expedition’s archaeological, historical and linguistic aspects. He was accompanied by army doctor Louis Vaillant, responsible for topography, astronomy and natural history, and photographer Charles Nouette. They left Paris on 15 June 1906, traveling for ten days by train as far as Tashkent. From there they continued by local train to Andizhan, where they set about preparing their expedition; and on 11 August they set off with 2 cossacks and 30 horses. They were to travel on horseback for over two years.

Their first destination, at the end of August 1906, was Kashgar, already visited in June by Aurel Stein. During six weeks of excavating in Kashgar, Pelliot collected manuscripts from the three caves and the Tegurman ruins. While there, he learned that that the Buddhist caves at Kucha had already been visited several months earlier, by the Germans, Japanese and Russians. On 18 October, the expedition travelled 300 kilometers eastwards from Kashgar and after two weeks reached the ruins of the monastic city of Tumshuk, already excavated by Sven Hedin, where Pelliot found a previously undiscovered Buddhist sanctuary. On 15 December, they continued to Kucha, arriving on 2 January 1907. Bypassing the Buddhist remains already visited by others, Pelliot concentrated initially (16 March to 22 May 1907) on Duldur-aqur, to the south of Kucha, near Kumtura, where findings included 200 fragments in Chinese as well as the first manuscripts in Brahmi script, all that remained of a monastic library. In the Subashi area, north-east of Kucha (10 June to 24 July), Pelliot collected more fragments, including 208 poplar-wood fragments in Sanskrit (Udarnavarga). Saldirang yielded caravan permits and woodslips inscribed in the lost language of Kuchean (Tocharian B or West Tocharian).

After eight months in Kucha, the expedition pressed on via Urumqi to Dunhuang, where they remained from 12 February to 7 June 1908. From 27 February to 27 May they camped at Mogao and explored the 500 or so caves, the ‘Caves of a Thousand Buddhas’, containing paintings from the 4th century onwards. Stein had been the first westerner to visit these caves but had not carried out any extensive research having concentrated mainly on the Library Cave (Cave 17). Pelliot and Nouette set about documenting the Mogao caves and contents in systematic detail, making comprehensive photographic and written records. On 3 March, they were allowed to enter the library cave where they found tens of thousands of manuscripts in Chinese, Tibetan, Sanskrit and Uighur, as well as large paintings on silk, hemp and paper. Pelliot was allowed to spend a full three weeks in the library cave, working tirelessly to check through thousands of scrolls. He selected a range of religious, secular and local texts which he judged to contain new information or to be of linguistic interest. He also collected statues and paintings on silk.

In June 1908 the expedition set off again, reaching Xian on 28 September 1908. There, they spent a month organizing their findings and preparing them for transport to Peking and onwards to Paris. After almost 2 years on horseback, they were now able to travel by train, from Zhengzhou to Peking. Vaillant and Nouette returned immediately to Paris, by sea, with the expedition’s findings packed in crates, while Pelliot stayed on in Peking where he presented a few manuscripts, retained for the purpose, to Chinese scholars. As a result of this the Chinese scholarly world in Beijing became aware of the importance of the Dunhuang library cave find and established a committee which lobbied the government to send representatives to retrieve the remainder of the cave’s contents (see Chinese Collections). Pelliot continued with his research in Beijing and before returning to France he purchased a total of 30,000 books which were to form a regional studies library.

Once in Paris, the books and manuscripts were sent to the Bibliothèque nationale and the other findings (statues, frescos, objects and over 200 paintings and banners) were kept at the Louvre, where some were exhibited before being transferred to the Musée Guimet in 1945–46. The French Museum of Natural History received specimens including 800 plants, 200 birds, mammals, insects and geological specimens.

Some time after his return to Paris in 1909, Pelliot began to make an initial inventory of the Chinese language manuscripts, completed in 1920 and published in Chinese in 1923. He also published numerous articles and studies, which remain authoritative, including on Manicheanism and Nestorianism in China. Pelliot’s colleagues worked on the Tibetan and other languages. This was slow and painstaking work and the inventory was not completed until 1932 (by Naba Toshida). Compilation of a descriptive catalogue of the Chinese collection began in 1952 and is now nearing completion; all volumes except one have been published. Marcel Lalou’s ‘Inventaire des manuscrits tibétains’ was published in 1939 and, in the same year, the 30,000 books brought back by Pelliot were catalogued. Much cataloguing work has also been carried out on the Sanskrit, Uighur and other manuscript collections at the BnF. Of the other material, all the statues, paintings and photographs have been catalogued and many have been published.

Content and Access

© Guimet Museum

The 30,000 books and all the manuscripts brought back by Pelliot, remain in the collections of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the other material at the Musée Guimet, which also holds the entire collection of Nouette’s photographs of the expedition and Pelliot’s diaries and other archives.

1. Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

1.1 BnF collections

The manuscript collection comes mainly from the Dunhuang Library Cave and contains many secular texts: a basis for the development of economic, social and legal history of medieval China. In addition, the BnF holds around 100 coins (7th and 8th centuries), from the Kucha oasis. The Pelliot collection at the BnF is divided by language into several fonds (collections):

- Pelliot Tibétain, the largest, with 4,174 items

- Pelliot Chinois, the second largest, with around 3,000 scrolls (including a few illuminated manuscripts) plus booklets, concertinas, Buddhist paintings and woodblock prints and around 700 fragments

- Pelliot Sanskrit containing almost 4,000 fragments

- Pelliot Kuchean (Tocharian), with around 2,000 woodslips and paper fragments

- Pelliot Sogdian

- Pelliot Uighur

- Pelliot Khotanais

- Pelliot Xixia (Tangut), with several hundred items, mostly woodblock prints

- Pelliot divers

1.2 BnF access

The entire Pelliot collection is housed in the original BnF building known as the Richelieu, situated near the Louvre in the centre of Paris. All of the manuscripts have been microfilmed (and are currently being digitized) because they are too fragile to display and may be handled only rarely. Pelliot’s 30,000 books are also at the Richelieu, along with the 100 coins.

For details of location and opening hours, click here (informations pratiques).

To obtain access to the reading room at the Richelieu, it is necessary to become a reader.

Click here for details on how to obtain a reader’s card for the Richelieu site.

Readers may apply for permission to view the manuscripts or microfilm by e-mailing the department of oriental manuscripts

2. Musée Guimet

2.1 Musée Guimet collections

The Guimet holds paintings from Dunhuang and artefacts including statues, paintings and banners from various Silk Road sites. Some of these are on permanent display in the galleries. They have been reproduced in two volumes: Les arts de l’Asie centrale: La collection Pelliot du musée Guimet (Kodansha). The Guimet has also preserved thousands of glass plates from Nouette’s photographs; thousands of coins from the expedition; and Pelliot’s detailed notebooks where he reputedly recorded every finding and every inscription witnessed.

2.2 Musée Guimet access

The museum is open from 10.00 to 18.00, every day except Tuesday. For further information and contact details, Visit the Musée Guimet website.

French Collections on the IDP Website

The BnF and the Musée Guimet were founder members of IDP. Much of their material has now been digitized and it is hoped that it will soon be available online.

Number of Manuscripts by Language/Script on IDP in France as of 08/09/2023

| Language(s)/Script(s) | Number of manuscripts/blockprints | Number Digitised |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Phags-pa (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Arabic (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Arabic (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Avestan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Avestan (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Bactrian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Brahmi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Chinese (lang.) | 4,024 | 4,022 |

| Chinese (script) | 9 | 8 |

| East Syriac Maḏnḥāyā (Nestorian) (script) | 0 | 0 |

| English (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| forged | 0 | 0 |

| French (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Gandhari Prakrit (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| German (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Greek (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Greek (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Gupta (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Hebrew (script) | 1 | 1 |

| Hepthalite (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Judaeo-Persian (lang.) | 1 | 1 |

| Kharosthi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Khitan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Khitan large (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Khotanese (lang.) | 66 | 66 |

| Kok Turkic (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Latin (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Manichaean (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Middle Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Mongolian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Mongolian (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Nagari (script) | 0 | 0 |

| New Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| not applicable | 1 | 1 |

| Old Turkic (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Pahlavi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Pala (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Parthian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Sanskrit (lang.) | 13 | 13 |

| Siddham (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Sogdian (lang.) | 44 | 44 |

| Sogdian (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Syriac (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tangut (lang.) | 1 | 1 |

| Tangut (script) | 1 | 1 |

| Tibetan (lang.) | 4,453 | 3,806 |

| Tibetan (script) | 10 | 9 |

| Tocharian A (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian B (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian C (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tumshuqese (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| unidentified (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| unknown (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Uyghur (script) | 20 | 20 |

| Zhang-zhung (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Total* | 9,631 | 7,900 |

Bibliography

- Benveniste, Emile, Textes sogdiens edites, traduits et commentes. Mission Pelliot en Asie Centrale. Paris: P Geuthner, 1940.

- Cocheteux, Marie-France (ed.), Takahashi, Agnès (ed.), Sérinde, Terre de Bouddha. Dix siècle d’art sur la route de la soie. Paris: RMN, 1995.

- Musee Louis-Finot, Pascalis, Claude, La collection tibetaine : Musee Louis Finot / par Claude Pascalis.. Hanoi: Ecole francaise d’Extreme-Orient, 1935.

- Manuscrits Ouigours du IX-X siecle de Touen-huang (2 vols). Paris: Peeters France, 1986.

- Hopkirk, Peter, Foreign Devils of the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. London: John Murray, 1980.

- Catalogue des manuscrits Chinois de Touen-Houang (Fonds Pelliot Chinois), vol. I: nos. 2001-2500. Paris: Bibliotheque Nationale, 1970.

- Catalogue des manuscrits Chinois de Touen-Houang (Fonds Pelliot Chinois de la Bibliothèque nationale), vol. III: nos. 3001-3500. Paris: Fondation Singer-Polignac, 1983

- Catalogue des manuscrits Chinois de Touen-Houang (Fonds Pelliot Chinois de la Bibliothèque nationale), vol. IV: nos. 3501-4000. Paris: Fondation Singer-Polignac, 1991.

- Catalogue des manuscrits Chinois de Touen-Houang (Fonds Pelliot Chinois de la Bibliothèque nationale), vol. V: nos. 4001-6040. Paris: Fondation Singer-Polignac, 1995.

- Pelliot, Paul, Les grottes de Touen-Houang: peintures et sculptures bouddhiques des époques des Wei, des T’ang et des Song. Paris: Librairie Paul Geuthner, 1914-1924.

- Pelliot, Paul, Grottes de Touen-houang: carnet de notes de Paul Pelliot: inscriptions et peintures murales I,- grottes 1 à 30. Paris: Collège de France, Instituts d’Asie, Centre de recherche sur l’Asie centrale et la Haute Asie, 1981.

- Pelliot, Paul, Grottes de Touen-houang: carnet de notes de Paul Pelliot: inscriptions et peintures murales II.-, grottes 31 à 72. Paris: Collège de France, Instituts d’Asie, Centre de recherche sur l’Asie centrale et la Haute Asie, 1983.

- Pelliot, Paul, Grottes de Touen-houang: carnet de notes de Paul Pelliot: inscriptions et peintures murales III.- grottes 73 à 111a. Paris: Collège de France, Instituts d’Asie, Centre de recherche sur l’Asie centrale et la Haute Asie, 1983.

- Pelliot, Paul, Grottes de Touen-houang: carnet de notes de Paul Pelliot: inscriptions et peintures murales IV.- grottes 112a à 120n. Paris: Collège de France, Instituts d’Asie, Centre de recherche sur l’Asie centrale et la Haute Asie, 1984.

- Pelliot, Paul, Grottes de Touen-houang: carnet de notes de Paul Pelliot: inscriptions et peintures murales V.- grottes 120n à 146. Paris: Collège de France, Instituts d’Asie, Centre de recherche sur l’Asie centrale et la Haute Asie, 1986.

- Pelliot, Paul, Grottes de Touen-houang: carnet de notes de Paul Pelliot: inscriptions et peintures murales VI.- grottes 146a à 182. Paris: Collège de France, Instituts d’Asie, Centre de recherche sur l’Asie centrale et la Haute Asie, 1992.

- Shishkina, G.V., Pavchinskaja, L.V., ‘”Les Quartiers de potiers de Samarcande entre le IXe et le début du XIIIe siècle,” “La production céramique de Samarcande du VIIIe au XIIIe siècle”‘. In Terres secrètes de Samarcande Céramiques du VIIIe au XIIIe siècle. Paris: Institut du Monde Arabe, Caen, Toulouse, 1992-3.

- Soymie, Michel (ed.), Catalogue des Manuscits Chinois de Touen-Houang. Paris: , 1991.

- Stein, Rolf A., ‘Du récit au rituel dans les manuscrits tibétains de Touen-houang’.

- Trombert, Eric (ed.), Ikeda, On (ed.), Zhang, Guangda (ed.), Les manuscrits chinois de Koutcha. Fonds Pelliot de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Paris: Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises du Collège de France, 2000.

- Vandier-Nicolas, Nicole, Hambis, Louis (ed.), Bannières et peintures de Touen-houang conservées au Musée Guimet. In Mission Paul Pelliot, 14-15. Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1974-76.

Consult this page for details of publications on the Musée Guimet holdings, by the Collège de France / Centre de Recherche sur l’Asie Centrale et la Haute Asie.

If you have feedback or ideas about this post, contact us, sign in or register an account to leave a comment below