IDP Collections in Japan

This summary of the history and make-up of the collections held in Japanese institutions was produced by the IDP team, led by Susan Whitfield, in December 2005. The information was last updated in November 2010. While we are keeping this text up as a background resource, please be aware that new information may have come to light since its initial writing.

The Otani Explorations in Chinese Central Asia

The Otani Explorations in Chinese Central Asia

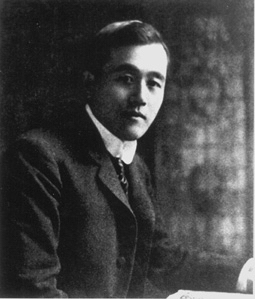

The Otani expeditions refer to the three trips to Central Asia between 16 August 1902 and 10 July 1914, carried out under the leadership of Count Otani Kozui (1876–1948), the 22nd abbot of the Nishi Honganji monastery in Kyoto (also written “Nishi Hongwanji”). The aim of the expeditions was to investigate Buddhist sites and to collect ancient manuscripts.

While studying in London, Otani had traveled all over Europe and met several other explorers, among them the Swede Sven Hedin and the Hungarian/British Aurel Stein. Otani dreamed of exploring Central Asia and influenced by these people he decided to organize his own expedition.

Because Chinese Central Asia had once played a decisive role in the eastward spread of Buddhism, Otani’s objective was to explore and excavate this region with the eyes of a Buddhist follower, especially seeking out old sutras.

The members of the expedition wrote diaries and although there are no detailed descriptions of all archaeological objects the main events of the expedition are recorded. The diaries and photographs of the expedition, as well as the botanical specimens, are stored together at the Ryukoku University Library.

First Expedition (1902–4)

Members:

- Kozui Otani (age 27), head of expedition

- Koen Inoue (31)

- Eryu Honda (27)

- Tesshin Watanabe (29)

- Kenyu Hori (23)

The first expedition was accomplished on Otani’s return to Japan from London. On 16 August 1902, Otani left London and returned to Japan via Central Asia. The five participants met on 21 August in St. Petersburg, Russia and proceeded via Baku, Samarkand, Andizhan, Osh, and the Terek Pass, reaching Kashgar on 21 September. Here, having discussed their further traveling plans with the British representative, Lt. Col. Miles, the members of the expedition decided to separate into Indian (Otani, Inoue and Honda) and Central Asian teams (Watanabe and Hori) and proceed in two separate groups.

The two groups left Kashgar together on 27 September and, moving eastward on the southern route reached Yarkand. From here, they both moved southwest to Tashkurgan. On 14 October, the Indian and Central Asian teams divided and continued to the south and east, respectively.

The Indian team under the leadership of Otani traveled with 3 horses and 17 camels. They crossed the Mintaka Pass and, by way of Gilgit, arrived in Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir, on 9 November. They returned via India.

Meanwhile, the Central Asian team returned to Yarkand and travelled east on the Southern route. They spent about forty days at Khotan excavating ancient city sites in the area. They left on 2 January 1903 and crossed the Taklamakan desert to the Northern route. They visited Aksu and Turfan and on 20th February arrived back in Kashgar.

They soon set off again travelling via Maralbashi, Tumshuk, Aksu, and Bai on 10 April they reached the site of Kizil near Kucha. They stayed in Kucha for about four months, studying various ancient sites, such as eastern and western Subashi, Kizil caves, Kumtura caves, and Duldur-okur. Because Khotan on the had already been explored by the Stein and Turfan had been explored by the German expeditions, Otani’s team concentrated on excavating the as yet unexplored site of Kucha.

Following this the team returned home via Turfan, Urumqi, Hami and Xi’an.

Second Expedition (1908–9)

Members:

- Zuicho Tachibana

- Eizaburo Nomura

The two members of the second Otani expedition traveled from Beijing via Outer Mongolia to Urumqi, reaching Turfan on 15 November 1908. In Turfan, they excavated at the sites of Yarkhoto, Murtuk, Karakhoja, and Toyuk. They moved on to Kizil and explored Buddhist caves at Kumtura and elsewhere, where they found a number of old Chinese documents. Between 25 February and 6 May, 1909 Nomura conducted surveys around Kucha and on 29 March in the sand inside the Kumtura caves he found a manuscript dated to AD 782. Tachibana, discovered an early fourth century manuscript written by one Li Bo, Chief Aide Administrator of the Western Regions in sands near Loulan. The expedition also recovered a large number of manuscript fragments at the Toyuk Buddhist caves.

Their expedition route was as follows:

Peking, Outer Mongolia, Gucheng, Urumqi, Turfan, Karashahr, Korla, splitting…

Tachibana — Lop Desert, Loulan, Khotan, Yarkand

Normura — Kucha, Kashgar

Both, after rejoining — India

Third Expedition (1910–14)

Members:

- Zuicho Tachibana

- Koichiro Yoshikawa

- Tesshin Watanabe

- A. O. Hobbs

- Li Yuqing

In 1910 Tachibana, after having conducted a survey of Indian Buddhist sites together with Otani, returned to London. On 16 August, receiving an order to accompany the 18-year old Hobbs, he left London for the third Central Asian expedition. On 19 October Tachibana reached Urumqi and then moved on to Turfan. From there, he set off with Hobbs’s baggage for Kucha via the southern route. He first crossed the Lop Nor desert to reach the city of Cherchen, then recrossed the desert northward to Kucha. Hobbs, who had already arrived in Kucha, contracted smallpox and died. Tachibana took his remains to Kashgar for burial. After this, he left for Khotan, arriving on 7 May 1911. Here he conducted a survey together with Watanabe.

Meanwhile, Yoshikawa received orders in Japan to join this expedition accompanied by Li Yuqing, the Chinese chef working at Otani’s residence, the Villa Niraku in Kobe. The Yoshikawa team reached Dunhuang on 5 October and waited for Tachibana. However, Tachibana was delayed which meant that Yoshikawa used the time to explore the Mogao Buddhist caves near Dunhuang, to take photographs of the wall paintings and Buddha statues, prepare rubbings, and acquire old manuscripts. Once Tachibana arrived, the two explorers stayed at the Mogao caves from 30 January until 1 February and purchased 369 manuscript scrolls from Wang Yuanlu for 400 tael. These Dunhuang manuscripts also included the ones acquired separately by Yoshikawa. The team moved to the northern route and excavated Buddhist manuscript fragments at Toyuk, purchased gravestones, documents buried with the deceased (appointment documents, funerary inventories), recycled paper matter (government documents), and textiles from excavations of the cemeteries at Astana and Gaochang. After Tachibana left for Japan, Yoshikawa continued to the Tianshan Mountains to make collections of plant specimens. On 5 January, 1914 he left Urumqi for Japan.

Tachibana — London, Omsk, Urumqi, Turfan, Lop Desert, Kashgar, Khotan, Tibetan territory, Keriya, Dunhuang (joining Yoshikawa)

Yoshikawa — Shanghai, Hankou, Xi’an, Dunhuang (joining Tachibana), Turfan, Urumqi

Tachibana — Siberia

Yoshikawa — Turfan, Kucha, Kashgar, Khotan, Yili, Urumqi, Baotou, Hohehot, Peking.

Collections: Contents and Access

The Otani expeditions returned to Japan with a collection of ancient manuscripts, woodslips, wall paintings, sculptures, silk paintings, textiles, coins, seals, nine mummies and archaeological documentation. The items originally went to Kyoto’s Nishi Honganji Monastery but were later moved to Villa Niraku at the foot of the Rokko mountain in Kobe, where they were also organized. With respect to the categorization, organization and dispersal of this collection, please see Fujieda 1989, Kudara 1996 and Katayama 1999 (see bibliography below). Below are some of the most important items within the collection.

a) Chinese Buddhist sutras

The Otani expedition excavated a large number of sutras from the remains of a Buddhist monastery in Turfan and elsewhere. Below are some representative items from this collection.

- a Western Jin manuscript of the Buddhasaṃgītisūtra (T.810) dated to 306 (present location unknown);

- a manuscript of the Lotus Sutra (translated by Kumarajiva in 406) dated to 411;

- a manuscript of chapter 21 of the Lotus Sutra (presently in the Ryukoku University collection);

- a manuscript of the Mahaprajnaparamita Upadesa (Treatise of the Great Perfection of Wisdom) translated by Kumarajiva (405);

- the famous first dated paper manuscript called the ‘Li Bo document’ from 328.

b) Non-Chinese documents

The Central Asian sites yielded many documents in languages other than Chinese, including Buddhist sutras written in Sanskrit using the Brahmi script, Buddhist sutras and Manichaean documents in Sogdian, Tibetan, Tangut, and Uighur. For example, among the Buddhist works belonging to the Pure Land Sect, the collection includes an Uighur translation of the Kanmuryoujukyou (Contemplation on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life) Sutra.

c) Art and historical material

In this respect, the third expedition proved to be the most important one. The explorers excavated ancient tombs in Astana and Gaochang, extracting nine mummies and collecting many burial objects and ancient documents used during the funeral.

In 1914, Count Otani, having taken responsibility for a bribery scandal, resigned as the abbot of the Nishi Honganji Monastery. As a result, he had difficulties continuing his explorations in Central Asia and the collections were dispersed to China, Korea, and Japan. After his resignation, Otani shifted his base to the Chinese cities of Shanghai and Lüshun. About this time, part of the collection from Villa Niraku was shipped to the Otani Villa in Lüshun. After that, some of these objects were shipped back to Japan, The Buddhist sutras and statues remaining in the villa were later transferred to the Kantocho Museum (present-day Lüshun Museum). Following this in 1954, 620 items from this collection, including the Dunhuang manuscripts, were transferred to Beijing Library (the present-day National Library of China), while the fragments of Buddhist paintings were transferred to the Chinese Museum of History in Beijing. A sizable collection remained in the Villa Niraku in Kobe. The villa and its collection was subsequently sold to Fusanosuka Kuhara. Kuhara later presented the collection as a gift to Terauchi Masatake, an old friend, who was then Governor-General of Korea, and it was housed in the Korean Government General Museum (now in the National Museum of Korea, Seoul).

Beside these, some of the artefacts, photographs, botanical specimens and mummies brought back by the Japanese expeditions have gradually been sold into private and public collections both in Japan and abroad. Consequently, the Japanese collection, unlike famous collections in other countries, is to a large degree divided between public institutions and private collectors. Moreover, in the case of Japanese collections, the exact origin and history of the material is not always clear. Generally speaking, the different owners attached their own seal impression or made some other marking on the item, or mounted it in some patrticular way.

Main location of the Otani Collections

- Lüshun Museum, China: material from Turfan, including 16,035 Buddhist manuscript fragments, non-Chinese documents and various art objects. See Chinese Collections.

- Chinese Museum of History. See Chinese Collections.

- National Library of China: 621 Dunhuang scrolls moved from Lüshun Museum. See Chinese Collections.

- National Museum of Korea: c. 2,000 art objects, including wall paintings. See Korean Collections.

- In Japan, items from the Otani expeditions are housed in Ryukoku University, Tokyo National Museum, and Kyoto National Museum. Other museum and libraries have material from Central Asia acquired elsewhere. These are listed below.

Central Asian Collections in Japan

1. Ryukoku University

1.1 The Otani Collection at Ryukoku University

Among the artefacts from the Otani expeditions that were dispersed in Japanese and foreign collections, a portion is currently located in the Omiya Library of the Academic Information Centre, Ryukoku University.

In 1949, a year after the death of Count Kozui Otani at the age of seventy-three, artefacts filling two wooden boxes were discovered at the Villa Niraku and were donated to Ryukoku University. Beside precious manuscript material (scrolls, booklets, separate folios, and wooden slips), the boxes received by the University contained printed documents, silk paintings, textiles, plant specimens, coins, rubbings, and archeological documentation. Together, these nine thousand items came to be known as the Otani Collection at Ryukoku University. The Dunhuang and Silk Road collection consists of the following four groups:

- (a) Eight thousand odd items from the Otani expeditions discovered after the death of Kozui Otani in two wooden boxes at the Nishi Honganji Monastery;

- (b) Fifty-five items donated from the Tachibana collection;

- (c) Painting fragments and 166 photographs from the Yoshikawa collection;

- (d) Items acquired from other sources.

1.1.1 Material written in Chinese

One of the objectives of the Otani expeditions was the collection of Buddhist scriptures, therefore the Japanese explorers were particularly interested in sites yielding large quantities of manuscript material, such as the Buddhist sites of Kucha and Turfan, as well as the Dunhuang caves.

(a) Manuscript material

The Dunhuang documents were obtained when Tachibana and Yoshikawa visited Dunhuang during the third Otani expediton in 1912. Although large numbers of documents had already been purchased by Stein (1907) and Pelliot (1908), Tachibana was still able to acquire over three hundred items, including important finds such as the Lotus Sutra (fifth century) and the first volume of the Muryoujukyo sutra (sixth century).

(b) Secular documents

Among the secular material there are documents of land administration (fragments related to giving, requesting, and returning land in Turfan) and economic affairs (Oda 1984,1990).

Among the main items in the collection are the aforementioned ‘Li Bo document’ and a scroll (718) acquired by Yoshikawa in Dunhuang during the third expedition, which represents part of the Bencao jizhu xulu, often called the ancestor of Chinese pharmacology. The fragments gathered by the Otani expeditions in the cemetery complexes near Turfan originally were discarded administrative documents recycled to be used at funerals.

1.1.2 Non-Chinese material

The non-Chinese material consists of two major categories: religious documents (Manichaean scriptures, Nestorian Christian texts) and secular documents with social and economic content (contracts, receipts and expenditures, correspondence). The Ryukoku University collections contains texts written in 15 different languages (including Sanskrit, Tokharian, Sogdian, Khotanese, Turkic, Uighur; Tangut, Mongolian, and Tiibetan) using thirteen different scripts (including Brahmi, Kharosthi, Sogdian, Manichaean, and Uighur).

Representative items include the Kharosthi wood slips (found in Turfan; ca. fifth century), fragments of an illustrated Uighur copy of the Sudana Jataka (found in Turfan; ca. thirteenth–fouteenth century), and a Khotanese copy of the Book of Zambasta written in the Brahmi script (found in Turfan; ca. eighth-ninth century) (Kudara_1996).

1.1.3 Burial Items

The Astana and Gaochang cemeteries in the Turfan area yielded several silk paintings which decorated the ceiling and walls of the tombs. These include four variations of the Fuxi-Nüwa diagram. All of them were obtained by Yoshikawa in 1912 during the third expedition.

1.1.4 Art objects, archaeological documentation, plant samples, textiles

Art objects in the collection include a statue head, Buddha tiles, silk paintings, and stamped images.

1.1.5 Other

Nishi Honganji Monastery

In addition to the above material which was brought over from the Nishi Honganji Monastery, there are also other items donated to the collection by Tachibana, Yoshikawa, Nomura and their descendants. These items include expedition equipment, survey diaries, notes (sketches, watercolours, maps), letters, and photographs, all of which provide an important witness to the conditions during the expeditions.

Moreover, Ryukoku University and the National Ethnographic Museum houses the ethnographic and other material collected during the Indo-Tibetan survey, which was carried out by Aoki Bunkyo and Tada Tokan in parallel with the Central Asian expeditions.

1.2 Access to the Collections

Omiya Library

125–1 Daikutcho

Omiya Higashihairu

Shichijo-dori

Shimogyo-ku

Kyoto

Japan 600–8268

In order to use the collection, readers are required to make an appointment in advance.

2. The National Museum, Tokyo

The Tokyo National Museum comprises four buildings in the Ueno Park built on the old site of the Kaneiji Temple. The oldest building, which was completed in 1909, is used to display an architectural exhibit. The central building, completed in 1937, houses Japanese art. The Treasure House was built in 1964 for a collection of 319 items of seventh century art from the Nara Horyuji Temple. The fourth building was completed in 1968 and today it is used to display Asian art, Chinese calligraphy, and Central Asian art. The museum is one of three National Museums (the others being in Kyoto and Nara) and holds a collection of 88,000 items.

All the items from the Otani expeditions were purchased in 1964 by the Japanese Society for the Preservation of Culture and were moved to the Tokyo National Museum in 1967. The collection consists of archaeological objects excavated at various sites in Xinjiang, Chinese and Uighur manuscripts and woodslips from Turfan, Dunhuang and other sites; and paintings excavated at Dunhuang and Turfan. The museum also houses a few items under an exchange agreement with the Guimet Museum. Moreover, there are also several Central Asian items acquired from other sources.

For a long time, part of the Villa Niraku collection had been kept at the Imperial Gift Museum of Kyoto (today’s National Museum of Kyoto), before it was transferred, at the end of World War II, to Kimura Shinzo. After that, the state had acquired the collection and now it is housed in the Oriental Collection (Toyokan) at the National Museum of Kyoto. Among the items there is an image of a winged apsaras, a painting of Buddha teaching the law (from Kizil), a standing Bodhisattva holding a parasol (from Bezeklik), and a bodhisattva head.

Access to the collections

13–9 Ueno Park

Taito-ku

Tokyo 110–8712

The Tokyo National Museum Website

A portion of the collection is on permanent display at the Central Asian Gallery. The manuscripts and paintings are not on permanent display and can be viewed upon a prior arrangement with the curator.

3. The National Museum, Kyoto

The museum was founded as the Imperial Museum of Kyoto in 1897. It was renamed ‘Kyoto Royal Museum’ in 1900 and in 1924 was given to the city of Kyoto as ‘Imperial Gift, Kyoto Museum’. In 1952 it became a National Museum under its present name.

The main exhibition hall was built in 1895, designed by Toguma Katayama. The new exhibition hall was completed in 1966. The new hall houses the permanent collections from Japan and East Asia, while special exhibitions are held in the older hall. There is a permanent gallery of calligraphy and also of Buddhist paintings. The museum has a collection of about 4,000 items, with an additional 6,000 items from temples and other places in its custody.

Kyoto National Museum holds Dunhuang and Turfan documents formerly in the Matsumoto and Moriya collections. The former consists of five items mounted on four scrolls said to come from the Kucha region and the latter seventy-two manuscripts reportedly from Dunhuang.

The collection includes five fragments, mounted onto four scrolls, of a Chinese translation of the Lotus Sutra, the Mahaprajnaparamita Upadesa, the Dazhidulun, the Dapin Sutra and the Upasaka.

Access to the collections

527 Chayamachi

Higashiyama-ku

Kyoto 605–0931

The manuscripts are not on display but may be seen by prior appointment in writing.

4. Gotoh Museum

The Gotoh Museum was founded by Gotoh Keita (1882–1959), the late Chairman of the Tokyu Corporation. His private collection of pre-modern Japanese, Chinese and Korean art was opened to the public in 1960. The museum holds special shows in the spring and autumn while the permanent collection is displayed in rotation during the rest of the year. The museum also has tea ceremony rooms and a garden.

Gotoh Museum has about twenty manuscripts from Dunhuang and other Silk Road sites.

Access to the collections

3–9–25 Kaminoge 3-Chome

Setagaya-ku

Tokyo 158–8510

The museum is closed on Mondays, national holidays and the next day following those. The exhibits are changed at the beginning of the year.

Hours: 10:00am to 5:00pm (entry to the museum limited until 4:30pm)

The Museum is open to the public from 9.30am to 4.30pm every day except Monday. The manuscripts are not on display and permission must be sought in writing in advance to see them.

5. Horyuji Temple, Nara

There is only a very small collection of manuscripts which is not generally accessible.

6. Kyushu University, Fukuoka

There is a small collection of manuscripts at Kyushu University, Fukuoka.

Kyushu University Website

7. Mitsui Bunko

Mitsui Bunko was founded in 1916, but closed during the Second World War and only re-opened in 1965. In 1985 it received a gift from the Mitsui family which included Dunhuang manuscripts.

Mitsui Bunko has a collection of 112 items, many of them Dunhuang manuscripts, including many formerly in the collection of Zhang Guangjian, an official in Gansu Province, China.

Access to the collections

5–16–1 Kamitakada

Nakano-ku

Tokyo

Written requests to see other manuscripts not on display should be made in advance.

8. Nakamura Shodo Museum, Tokyo

This was originally the Nakamura private collection. After decades of collecting Chinese calligraphy, especially examples from Dunhuang and Turfan from Chinese officials such as Wang Shunan, Mr Nakamura turned his house into a museum in 1936. In 1995 the Nakamura family donated the museum to the district government.

Access to the Collections

2–10–4 Negishi

Taito-ku

Tokyo

9:30–16:30 (Admission ends at 16:00), Closed Mondays and New Year holiday.

9. National Diet Library

The National Diet Library has a collection of forty-eight manuscripts from Dunhuang and other Silk Road sites most of which were originally in the Hamada collection and were acquired through the Inoue Bookshop. Forty-three are Chinese, two in Tangut and three in Tibetan. Most of the manuscripts are available on microfilm.

Access to the Collections

Rare Books Section, National Diet Library

10–1–1 Nagato-cho

Chiyoda-ku

Tokyo

The National Diet Library is open to all scholars. The manuscripts can be viewed on microfilm but special permission must be sought to see any of the originals and their accessibility depends on their state of preservation.

10. Neiraku Museum

74 Suimon-cho, Nara City

Neiraku Museum has a few Dunhuang and Turfan fragments bound in one large album.

11. Otani University

Otani University traces its origins back to 1665 when a seminary was established by the Nishi Honganji Temple Headquarters of the Jodo Shin school of Japanese Buddhism. It was reorganized as a modern university in Tokyo in 1901 and transferred to Kyoto in 1911. The Graduate School was established between 1953–55. The Shin Buddhist Comprehensive Research Institute was founded in 1981. The University has an enrollment of 4,800 and the Library contains over 600,000 volumes.

The University Library has a collection of thirty-eight manuscripts from Dunhuang, thirty-four of which were from the Otani Collection, three from the collection of the former President of the University and one from a university professor.

Access to the Collections

The Library

Koyama-kamifusa-cho

Kita-ku

Kyoto 603

The manuscripts are not on display but can be seen by prior appointment.

12. Seikado Bunko

Seikado Bunko was established in 1892 with the objective of preserving the distinct cultural identity of Japan and Eastern countries, in a response to the Westernisation following the Meiji Restoration. It therefore aimed to buy old books and artefacts from China and Japan. In 1907, the institution purchased the entire collection of a Qing bibliophile which included Song and Yuan printed books, and this formed the foundation of the collection. Seikado Bunko was formed as a legal institution in 1940 and in 1948 temporarily became a section of the National Library.

Seikado Bunko has a collection of 8 volumes of fragmentary manuscripts and documents from Turfan and other Silk Road sites. These were purchased in 1935 from Chinese bookdealers in Japan. Seven of the eight volumes appear to have previously belonged to Liang Yushu, an official in Xinjiang.

Access to the Collections

Okamoto 2–23–1

Setagaya-ku

Tokyo 157

Scholars from the level of university students may use the library with a letter of introduction. An appointment must be made in advance.

13. Tenri Central Library

The establishment of Tenri Library was planned in 1925 and the building was completed in 1930. This new Central Library housed the various libraries of the Tenrikyo Buddhist Church and was originally intended as a facility for the education of overseas missionaries. It also housed research materials for faculty members and was open to readers in general as a public library.

The Library currently holds 1,780,000 books, manuscripts and documents, about a third of which are in Western languages, the rest in Japanese and Chinese. The Rare Books Collection comprises 17,000 items.

Tenri Library has about twenty scrolls from Silk Road sites, including the bulk of Zhang Daqian’s collection and a manuscript identified by its postscripts as being discovered in the early nineteenth century in a stupa at Dunhuang. The manuscripts were acquired from various sources and include pieces in Tibetan, Tangut and Uighur. In addition, the Library has a Dunhuang and a Turfan painting from the Otani Expeditions.

Access to the Collections

Somanouchi 1050

Tenri

Nara 632

Tenri Library is a public library and is open to anyone over the age of 15 years. However, the Dunhuang manuscript collection is a closed collection and is only accessible on written request in advance to the librarian.

14. Toshodaiji Temple

Toshodaiji Temple was founded by the Chinese priest, Ganjin, in AD 759, dedicated to the Chinese southern Chan (Zen) sect of Buddhism. It has been regarded as the headquarters of the Ritsu-shu denomination in Japan for more than 1200 years. Ganjin was a monk in Chang’an and Luoyang, devoted to the study of the ritsu aspect of Buddhism.

Toshodaiji Temple has a collection of about 27 manuscripts from Dunhuang and other Silk Road sites. In 1980 Toshodaiji Temple presented three manuscripts to the Chinese Buddhist Association.

Access to the Collections

13–46 Gojo-cho

Nara

15. Oriental Institute, Tokyo University

The Oriental Institute has a collection of eleven manuscripts from Dunhuang and other Silk Road sites.

Access to the Collections

7–3–1 Hongo campus

Bunko-ku

Tokyo 113

Tokyo University Oriental Library Website

The manuscripts are not on display but may be seen by prior appointment in writing.

16. Yurinkan

Yurinkan was established as a private museum in 1926 by Fujii Zensuke (1860–1934). He made a collection of Chinese artefacts and manuscripts, ranging from Shang dynasty bronzes to Qing costumes, but his collection of seals is most renowned. Yurinkan has a collection of about one hundred manuscripts from Silk Road sites. Sixty pieces were originally in the collection of He Yansheng, the Qing official responsible for transporting the manuscripts from Dunhuang to Peking, and there are other Dunhuang manuscripts from other sources. In addition, Yurinkan has twenty-seven documents in languages other than Chinese, twenty-three in Uighur, but also Tibetan, Mongolian and Sanskrit.

Access to the Collections

Enshoji-cho 44

Okazaki

Sakyo-ku

Kyoto 606–8344

The museum is open on the first and third Sunday of each month from 12 noon to 3pm. There are six manuscripts on display, five fragments in glass cases and a small booklet. Written requests to see other manuscripts not on display should be made in advance.

17. Other Collections

Apart from the above, there are also about fourteen manuscripts in the Daitokyu Memorial Library in Tokyo, eleven in the Oriental Institute at Tokyo University, four at the Otani University, along with another thirty-four from the Otani collections. There are also manuscripts in private collections. There are, for example, the forty Dunhuang manuscripts from the collection of Kiyono Kenji, a famous collector in Kyoto before the Second World War, which today are owned his descendants. One of the largest collections in Japan is still hidden. The Haneda Memorial Hall at Kyoto University has photographs of seven hundred Dunhuang scrolls made by the late Professor Haneda which are still owned by an unnamed corporation in Osaka.

Collections: On IDP

In 2005 IDP signed a collaborative agreement with Ryukoku University to set up a Japanese web site and a digitisation centre. The site went live in early 2006 and images and data started being put online. A summary is given below showing the breakdown by language.

Number of Manuscripts by Language/Script on IDP in Japan as of 08/09/2023

| Language(s)/Script(s) | Number of manuscripts/blockprints | Number Digitised |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Phags-pa (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Arabic (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Arabic (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Avestan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Avestan (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Bactrian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Brahmi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Chinese (lang.) | 6,745 | 6,745 |

| Chinese (script) | 0 | 0 |

| East Syriac Maḏnḥāyā (Nestorian) (script) | 0 | 0 |

| English (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| forged | 0 | 0 |

| French (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Gandhari Prakrit (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| German (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Greek (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Greek (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Gupta (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Hebrew (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Hepthalite (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Judaeo-Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Kharosthi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Khitan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Khitan large (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Khotanese (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Kok Turkic (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Latin (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Manichaean (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Middle Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Mongolian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Mongolian (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Nagari (script) | 0 | 0 |

| New Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| not applicable | 0 | 0 |

| Old Turkic (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Pahlavi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Pala (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Parthian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Sanskrit (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Siddham (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Sogdian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Sogdian (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Syriac (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tangut (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tangut (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Tibetan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tibetan (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian A (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian B (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian C (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tumshuqese (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| unidentified (lang.) | 3 | 3 |

| unknown (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Uyghur (script) | 4 | 4 |

| Zhang-zhung (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Total* | 8,465 | 8,465 |

Bibliography

- Dabbs, Jack A., History of the Discovery and Exploration of Chinese Turkestan. The Hague: Mouton, 1963.

- Hopkirk, Peter, Foreign Devils of the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. London: John Murray, 1980.

- Mesnil, Evelyne, ‘Les Seize Arhat dans la peinture chinoise (VIIIe-Xe s.) et les collections japonaises: Prémices iconographiques et stylistiques’. Arts Asiatiques (1999): 66-85.

- Sugiyama, Jiro, Illustrated Catalogue of Tokyo Museum: Central Asian Objects brought back by the Otani Mission. Tokyo: Tokyo National Museum, 1971.

- Takeuchi, Tsuguhito, ‘On the Tibetan Texts in the Otani Collection’. In Haneda, Akira, Documents et archives provenant de l’Asie Centrale. Actes du Colloque Franco-Japonais, Kyoto, 4-8 octobre 1988.. Kyōto: Association Franco-Japonaise des Études Orientales, 1990.

If you have feedback or ideas about this post, contact us, sign in or register an account to leave a comment below