IDP Collections in Russia

This summary of the history and make-up of the collections held in Russian institutions was produced by the IDP team, led by Susan Whitfield, in December 2005. The information was last updated in November 2010. While we are keeping this text up as a background resource, please be aware that new information may have come to light since its initial writing.

Russian Explorations in Chinese Central Asia

Russian Explorations in Chinese Central Asia

Russia’s expansion into Turkestan (Tashkent, Samarkand and beyond) in the 1860s, stimulated both Russian and wider international interest in Central Asia and gave Russia and its allies a useful point of access to a region of increasing geopolitical importance. The Russian government had already established a reputation for supporting scientific inquiry and sharing the results with scholars worldwide through the Russian Geographical Society (RGS), founded in 1845 by scientists and explorers already experienced in exploration from the Arctic to Asia. From the 1860s, the RGS began to initiate expeditions to Central Asia, to map the region, facilitate trade, obtain strategic information and gain political influence, while also adding to scholarship in the fields of botany, zoology, entomology, geography, ethnography and archaeology. The RGS collaborated with other Russian institutions and individuals with regard to funding and reporting and, as a result, scores of Russian expeditions criss-crossed the region between 1870 and 1920.

In the 1860s and 1870s, expeditions by Przhevalsky (below), Ioann-Albert Regel, and others, tended to focus on cartography, botany and zoology but also began to report archaeological findings. Regel described ruined temples and Buddhist relics in the Turfan area, in 1878. Grigory Nikolaevich Potanin, who led four expeditions to the region between 1876 and 1892 surveying tens of thousands of miles and collecting plant, bird and mammal specimens, also described ruins in the desert sands. Others, such as M. M. Berezovsky and Koslov (below) took part in botanical expeditions by Potanin, Przhevalsky and others and subsequently went on to conduct archaeological research.

Soldier, geographer and naturalist Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky (1839–88) led four major expeditions between 1870 and 1885, crossing the Gobi desert to Tibet several times, as well as crossing the Taklamakan from north to south. He also visited Dunhuang and the Mogao caves and reported finding sand-buried ruins at Lop Nor. Przhevalsky died in 1888 in the foothills of the Tianshan at the start of his fifth expedition, which continued without him. His achievements included extensive mapping and the transfer of hundreds of botanical and zoological specimens to St Petersburg, including many new species. Przhevalsky is particularly noted today for discovering a wild population of Bactrian camels and a unique breed of wild Mongolian horse, named after him. His writings include Mongolia: The Tangut Country (1875-6) and From Kulja: Across the Tian Shan to Lob-Nor (1878). More controversial was his final book, which proposed Russian annexation and colonisation of western China, Mongolia and Tibet (see IDP News 27).

Przhevalsky’s work was continued by his student Pyotr Kuzmich Kozlov (1863–1935), who had taken part in Przhevalsky’s last two expeditions and who subsequently participated in at least six expeditions. Kozlov’s first independent expedition, (1899–1901) took him across the Gobi to the upper reaches of the Yangtse and Mekong rivers, surveying over 6,000 miles for the RGS. Findings returned to St Petersburg from this trip included samples of 2,000-year-old Bactrian textiles.

© Institute of Oriental Manuscripts

During his 1907–09 expedition, Kozlov made perhaps the greatest Russian contribution to Silk Road archaeology, when he excavated the ancient, sand-buried city of Kharakhoto (later excavated by Aurel Stein: also see IDP News 2) which had been destroyed by Ghenghis Khan in 1227. Kozlov’s findings included hundreds of Buddhist statues and paintings which he photographed and recorded. He also found thousand manuscripts and xylographs in the previously unknown language of Tangut, which he took to St Petersburg. Koslov’s Kharakhoto findings are described in his book Mongolia and Amdo and the Dead City of Khara-Khoto (1923). In his final expedition to Mongolia and Tibet (1923–26), Kozlov discovered a number of Xiongnu royal burials.

In 1898, ten years before Koslov’s Tangut discoveries, Turfan was visited by an expedition under the direction of Dimitri Aleksandrovich Klementz (1848–1914), Keeper at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) in St Petersburg. The expedition was funded by the Russian Academy of Sciences. Klementz, accompanied by his botanist wife, E. N. Klementz, was the first to conduct archaeological excavations on the northern Silk Road. Significant findings were made around Karakhoja, Astana and Yarkhoto, including Old Uighur, Chinese and Sanskrit manuscripts, painting fragments and runic objects. Klementz shared his findings with Grünwedel (see German Collections) who launched his first Turfan expedition as a result. In the spirit of international cooperation, the findings were also reported to the 12th International Congress of Orientalists in Rome in 1899, by Vasilii Vasilievich Radlov (1837–1918) and Sergei Fedorovich Oldenburg (below). This and Stein’s discoveries (see British Collections) further stimulated the international interest in acquiring and researching the antiquities of Central Asia. In Russia, the International Middle and East Asian Studies Association was founded, to undertake ethnographical and archaeological exploration. The Russian Committee for Middle and East Asian Studies under the patronage of the Russian Emperor became the core of the Association, with Radlov as chairman and Oldenburg as vice-chairman. Its stated purpose was to “send expeditions to study those cultural monuments and ancient Asian peoples that could shed the light on ancient cultural links between different great civilizations, and provide help to all international expeditions”. The Committee, under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, had the right to send representatives to exploration sites, to organize expeditions and to publish bulletins in Russian and French.

In 1900 Klementz, Oldenburg and Nikolai Ivanovich Veselovsky (1848–1918) presented their ‘note on the organization of an archaeological expedition to the Tarim Basin’, in which they pointed out that the economic and commercial development of the region would entail serious damage for the archaeological remains in the area.

Sergei Fedorovich Oldenburg (1863–1934) graduated from St Petersburg University in 1885 with a major in Indian studies. After further training in France, Britain and Germany, he took up a teaching post at St Petersburg University in 1889. In December 1916, just before the February 1917 revolution, Oldenburg was appointed director of the Asiatic Museum in St Petersburg and when the museum was reorganized into the Institute of Oriental Studies, he became its first director on 4th April 1930. After the 1917 revolution he was appointed minister of education in the provisional government. His other posts included Permanent Secretary of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR (1904–29) and editor of Bibliotheca Buddhica series (1897–1934). Oldenburg’s research ranged across the cultural and religious history of medieval India, the history of Buddhist art, literary texts, and the folklore and art of Central Asia. A particular area of interest was Serindia, the vast region of Central and Eastern Asia including Tibet, Mongolia and northwest China. Integrated study of Serindian cultures formed the main focus of Oldenburg’s two archaeological expeditions (1909–10 and 1914–15), known as the Russian Turkestan expeditions.

© Institute of Oriental Manuscripts

Oldenburg’s first Russian Turkestan expedition (1909–10) was organized by the Russian Committee for Middle and East Asian Studies, at a time when the findings of British, French and German expeditions to the region remained unpublished, apart from a small part of Grünwedel’s expedition findings (see German Collections), and Stein’s first expedition report (see British Collections). Oldenburg therefore consulted Grünwedel and Pelliot (see French Collections) for the details of their recent research, before planning his own route and objectives. The expedition left St Petersburg on 5th June 1909 with Oldenburg as director, artist-photographer Samuil Martynovich Dudin (1863–1929); (see below and article by Menshikov in IDP News 14), mining engineer Dmitri Arsenievich Smirnov and archaeologists Vladimir Ivanovich Kamensky and Samson Petrovich Petrenko. Unfortunately the two archaeologists were beset by illness and had to return to Russia from Urumqi. From St Petersburg, the team traveled by train as far as Omsk and then continued by steamboat to Semipalatinsk where they collected equipment forwarded from St Petersburg. From here they set off to Chuguchak in tarantasses (horse-drawn carts). Arriving at Chuguchak on 22 June, they engaged an interpreter, Bosuk Temirovich Khokho from Hami, and continued to Urumqi and Karashahr with groom Bisambai, cook Zakari and two cossacks Romanov and Silantiev.

On 22 August the expedition began to excavate at Shikchin near Karashahr, exploring the ruins of a monastic city. In the Turfan area they continued work in Yarkhoto, Karakhoja, Taizan, Kurutka, Tallikbulak, Sassikbulak, Sengim-agiz, Bezeklik, Murtuk, Chikkankul, Toyukmazar, Sirkip and the Lamjin gorge. On 19 December Oldenburg reached Kucha where he explored various sites, including the cave temples, around Ming-teng-ata, Subashi, Simsim, Kirish, Kizil, Kumtura, Torgalyk-akyp and Koneshahr. Oldenburg’s method was to take precise and clear photographs and compile extensive data in pursuit of archaeological results.

In 1910 the expedition findings were presented to the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology at the Russian Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg, where they were briefly catalogued. In 1931–32 they were transferred to the State Hermitage Museum where part of the collection has been on display since 1935. The collection includes murals, paintings, terracottas, about one hundred manuscripts (mainly fragments in Brahmi script), photography, and sketch-maps of archaeological and other sites.

Oldenburg’s brief expedition report was published in 1914 (Ольденбург С.Ф. Русская Туркестанская экспедиция 1909–10 г.. Краткий предварительный отчет. C 53 таблицами, 1 планом вне текста и 73 рисунками и планами в тексте по фотографиям и рисункам художника С.М. Дудина и планам инженера Д.А. Смирнова. СПб., 1914).

Oldenburg’s second Russian Turkestan expedition (1914–15) included artist V. S. Bikenberg, topographer N. A. Smirnov, photographer B. F. Romberg, seven Kazakh guards, a Chinese interpreter and the same photographer, Dudin, as on the first expedition. The expedition aimed to make a precise map of the Mogao caves at Dunhuang, including every level and cross- and longitudinal section, to take pictures and copies of the most important objects and to make a detailed description of the caves. The expedition left St Petersburg on 20th May 1914, with the route of Chuguchak-Gucheng-Urumqi-Anxi-Hami-Qianfodong – the last being the ‘caves of a thousand Buddhas’ at Mogao, near Dunhuang. On 20th August 1914 they reached their final destination. After a brief examination of the caves it was decided not to renumber them but to follow Pelliot’s numeration. Only three caves remained unregistered by Pelliot (since they were excavated after his visit) and these were designated by Oldenburg: A, B and C. Thorough exploration of the Mogao caves began on 24th August and ended on 25th November 1914. Oldenburg’s team used letters and numbers to identify each statue and painting and made a detailed record of each item through photographs, plans, sketches and notes. They found many fragments of artefacts and ancient manuscripts, all of which were carefully collected by Oldenburg who also purchased over 300 scrolls from local people. On the return journey from Dunhuang, Oldenburg revisited many sites around the Turfan oasis which he had explored during his first expedition.

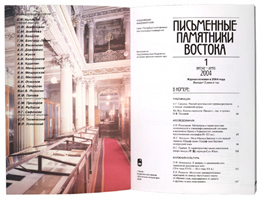

On 1st September 1915 the fragments, often crumpled or stuck together, sometimes with loess and clay, were put into packages and sacks and handed to the Asiatic Museum in St Petersburg (above), now the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM) and part of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Oldenburg’s collection of Dunhuang manuscripts and fragments from the fifth to the eleventh centuries is still housed today at the IOM in St Petersburg. The collection contains more than 19,000 items including tiny fragments. Many of the fragments from Mogao have burnt edges as a result of fires started in the Dunhuang caves by people taking shelter there over the centuries. The notes, sketches and photographs from the expedition provided the only available description of the caves until 1957, when Xie Zhiliu published his catalogue (Dunhuang yishu xulu (Catalogue of art at Dunhuang), Shanghai chubanshe, Shanghai, 1957).

Other Russian expeditions were led by K. G. E. Mannerheim (see Other Collections: Finnish Collections) and Sergei Efimovich Malov (1880–1957) who made two research trips (1909–11 and 1913–14) to study the language and culture of the Uighurs, Lobnorians and Salars. Malov subsequently provided the first description of these Turkic peoples.

Diplomatic representatives were also actively involved in collecting archaeological and cultural artifacts. Chief among these was Nikolai Fyodorovich Petrovski (1837–1908), Russia’s Consul General in Kashgar for twenty-one years from 1882. Petrovski was an influential figure in the region, playing host to expeditions such as Sven Hedin’s (Swedish Collections) and Aurel Stein’s (British Collections) and assisting with their travel arrangements. He assembled a significant collection of manuscripts and objects of art, buying from locals as well as undertaking his own archaeological research. He was particularly interested in the region from Kashgar to Kucha and Khotan, and the triangle formed by Kashgar, Khotan and Leh to the south. Like his British counterpart George Macartney (see British Collections), Petrovski purchased manuscripts and printed books in an unknown script which were later discovered to be forgeries.

The following paragraph, on Collections at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, gives further details of collections made by Russian representatives in Central Asia.

Collections: Contents and Access

1. Collections at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM), St Petersburg

© Institute of Oriental Manuscripts

The Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM) of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, holds a great number of manuscripts from Central Asia, in languages including Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mongolian, Tangut, Tocharian, Uighur, Khotanese and Saka. Petrovski’s collection contains mainly Saka and Sanskrit (Brahmi) manuscripts, plus a number of Tocharian documents. The collection of N. N. Krotkov, the Russian Consul in Urumqi and Kuldja, contains mainly Uighur texts and a few fragments of early wood-printed books from the 9th to 14th centuries. Berezovsky’s collection, numbering 1876 items, is characterized by precise information on the provenance of each item. In addition, the IOM holds collections of I. P. Lavrov, the Secretary of the Russian Consulate in Kashgar at the beginning of the twentieth century; of A. I. Kokhanovsky, the medical officer at the Russian Consulate in Urumqi; of A. A. Dyakov, Consul in Kuldja, and of Malov. The Archive of Orientalists at the IOM holds documents, personal papers and maps from some of the Russian expeditions to Central Asia, including those of Klementz, Malov and Oldenburg.

1.1 The Tangut Collection at the IOM

The IOM holds a unique Tangut collection, brought back from Kharakhoto by Kozlov’s expedition. Kozlov’s findings were originally stored in the museum of Emperor Alexander III (the Russian Museum), until they were transferred to the Asiatic Museum (now the IOM) in 1911. The collection consists mainly of manuscripts and old printed books in the dead language of the Tangut people who in the 10th century founded the Xixia state in present-day northwest China. There are also a large number of Chinese manuscripts among these materials. An inventory of the Chinese manuscripts was started by Aleksei Ivanovich Ivanov (1878–1937), Paul Pelliot (who visited Russia in 1910) and Vasilii Mikhailovich Alekseev (1881–1951). The work was continued by Nikolai Aleksandrovich Nevsky (1892–1934) and Konstantin Konstantinovich Flug (1893–1942). A full description of the Chinese part of the collection was published by Lev Nikolaevich Menshikov (1926–2005) [Меньшиков Л.Н. Описание китайской части коллекции из Хара-Хото. (Фонд П.К. Козлова). Прил. сост. Л.И. Чугуевский. М., 1984]. According to Menshikov, there are about 660 Chinese manuscripts and printed books in the IOM Tangut collection, most of them Buddhist. The collection also contains historical studies, Confucian classics, Daoist works, dictionaries, belles-lettres, engravings and prints. Professor Evgenii Ivanovich Kytchanov is continuing to work on the Tangut material and has published a number of catalogues and translations over several decades. Professor Ksenia Kepping (1937-2002) also worked on the documents and published several articles.

1.2 The Dunhuang Collection at the IOM

Oldenburg’s collections are divided between the IOM and the State Hermitage (below), with the manuscripts from his second expedition comprising the bulk of the Dunhuang collection at the IOM. The collection also includes about thirty manuscripts from Malov’s Khotanese expedition (1909–10) and 183 manuscripts collected by Krotkov. There is a total of about 19,000 items in the IOM Dunhuang collection, including 365 scrolls and a great number of fragments and small manuscripts. The majority of the manuscripts are Buddhist and only 900 are secular.

Study of the collection began in the late 1920s, with work by the Japanese researcher Kano Naoki. During the 1930s, cataloguing and description of the Dunhuang materials was started by Flug, who published a number of articles on the most important Buddhist and non-Buddhist manuscripts. In the 1950s, the work was continued by a small research group of four scholars: V. S. Kolokolov (1896–1979), Menshikov, V. S. Spirin and S. A. Shkolyar. By 1957 when Menshikov was appointed head of the Dunhuang group, only 3,640 items in the collection had been inventoried (2,000 by Flug and 1,640 by M. P. Volkova). The rest of the collection remained stored as it had arrived, in five packs, one box and one bag. It was therefore necessary to remove loess and other debris and carry out conservation and cataloguing work, before the collection could be described and studied. Later on, M. I. Vorobyova-Desyatovskaya, I. S. Gurevich, I. T. Zograf, A. S. Martynov and B. L. Smirnov joined the research group. Their joint efforts resulted in publication of the catalogue Description of the Chinese Manuscripts in the Dunhuang Collection at the Institute of the Peoples of Asia which was issued in 2 volumes in 1963 and 1967. The catalogue was organized into 2,954 descriptive entries, arranged in thematic sections. In 1999 the Shanghai Classics Publishing House issued this catalogue in Chinese and in 1994–2000 it published 17 facsimile volumes of the Dunhuang Chinese manuscripts in the IOM collection. Between 1960 and the 1980s, cataloguing and description of the collection was continued by Menshikov, Irena Kwong Lai You and L. I. Chuguevsky (1926–2000).

1.3 Access to the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, St Petersburg

To get access to the IOM, it is necessary to provide a letter of recommendation from your home university, museum, or other institution.

The opening hours of the reading room in the Novo-Mikhailosky Palace (Dvortsovaya naberezhnaya, N 18) are 10.00–18.00 Monday-Friday; closed Saturday and Sunday.

Selected items from the collections are on display. Advance permission must be obtained before these items can be seen.

The Department of Manuscripts and Documents of the IOM has full inventories and a card (paper) catalogue for the Dunhuang collections, plus two volumes describing the collection, 17 volumes of the facsimile edition Dunhuang Documents Held in Russia and microfilm of most of the collection. In order to protect originals, scholars are expected to consult the facsimiles, microfilms or digital images first. The original manuscripts may be viewed only exceptionally, by special request. In the case of fragile manuscripts, permission to view may be refused.

For further information see the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts’ website.

2. Collections at the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The State Hermitage also holds artefacts collected by numerous Central Asian expeditions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, from Dunhuang, Bezeklik, Kucha, Shikshin, Toyukmazar, Kumtura, Sassikbulak, Khotan, Kharakhoto, etc.

2.1 The Oldenburg Collection at the State Hermitage

The State Hermitage Museum holds artefacts and archaeological findings from the two Oldenburg expeditions, including Buddhist banners and hemp banner-tops (66 items); fragments of Buddhist paintings on silk (137 items); fragments of Buddhist paintings on paper (43 items); murals (24); textiles (38); fragments of manuscripts (8). In 1910 murals, textiles, and paintings from Oldenburg’s first expedition were presented to the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology (Kunstkamera) of the Russian Academy of Sciences and in 1931–1932 they were transferred to the Hermitage, where part of the collection has been on display since 1935. Additionally, since the late 1950s, 71 artefacts from the IOM in St Petersburg (above) have been on loan to the State Hermitage. The entire collection was restored, prior to being catalogued and studied by N. V. Dyakonova, M. L. Rudova-Pchelina and Menshikov. Selected items are now on permanent display.

The vast archive of Oldenburg’s expeditions, including his diaries, maps, documents and 2000 photographs, is also mostly at the Hermitage, although part remains at the IOM. After Oldenburg’s death his wife E. G. Oldenburg organised and typed up all his papers, including his field notes which had been very difficult to decipher. The full typescript of Oldenburg’s description of the caves at Dunhuang consists of six notebooks and 834 pages. E. G. Oldenburg also reviewed all the photographic plates of the Russian Turkestan expeditions in the collection of the State Hermitage, identifying them by comparison with Oldenburg’s written descriptions of the caves and inserting relevant photographic references at the end of each notebook. The artefacts and documents of Oldenburg’s second Turkestan expedition were published in six volumes by Shanghai Classics Publishing House.

2.2 Access to the Central Asian collections of the State Hermitage Museum

The State Hermitage Museum, at Dvortsovaya naberezhnaya, N 34, is open to visitors 10.00–18.00 every day except Monday.

Selected murals, statues and Buddhist paintings on silk and paper from the collections of Klementz, Berezovsky and Oldenburg are on permanent display in the Herrmitage. These include Buddhist and burial statues, vessels, murals and paintings, from Turfan, Sassikbulak, Toyukmazar, Shikcin, Kumtura and Khotan. Items from Dunhuang (artefacts, photos, pictures and maps) are also on display, in a separate room. The bulk of the Central Asian collection is in storage at the Hermitage.

For further information consult the Hermitage website.

3. Collections in Russian Geographical Society Archive, St Petersburg

The archive of the Russian Geographical Society was founded in 1845. It is a unique research resource, containing more than 60,000 files of which 13,000 contain ethnographic material, including on Central Asia. Among this material are travel notes, diagrams, photographs, maps and ethnographic objects from the expeditions of Przhevalsky, Potanin, Koslov and others.

For more information, consult the Russian Geographical Society Archive website (Russian language only).

Collections: on IDP

The Dunhuang collection at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (IOM) in St Petersburg is being digitized as part of IDP. The work began on 1 January 2004 and the Buddhist scrolls (with pressmark F-n) are now becoming available online. Digitisation of the fragments will follow. A summary is given below showing the breakdown by language.

Number of Manuscripts by Language/Script on IDP in Russia as of 08/09/2023

| Language(s)/Script(s) | Number of manuscripts/blockprints | Number Digitised |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Phags-pa (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Arabic (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Arabic (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Avestan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Avestan (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Bactrian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Brahmi (script) | 1 | 0 |

| Chinese (lang.) | 2,586 | 287 |

| Chinese (script) | 1 | 1 |

| East Syriac Maḏnḥāyā (Nestorian) (script) | 0 | 0 |

| English (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| forged | 0 | 0 |

| French (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Gandhari Prakrit (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| German (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Greek (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Greek (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Gupta (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Hebrew (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Hepthalite (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Judaeo-Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Kharosthi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Khitan (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Khitan large (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Khotanese (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Kok Turkic (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Latin (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Manichaean (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Middle Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Mongolian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Mongolian (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Nagari (script) | 0 | 0 |

| New Persian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| not applicable | 0 | 0 |

| Old Turkic (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Pahlavi (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Pala (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Parthian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Sanskrit (lang.) | 2 | 0 |

| Siddham (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Sogdian (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Sogdian (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Syriac (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tangut (lang.) | 3,510 | 48 |

| Tangut (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Tibetan (lang.) | 3 | 0 |

| Tibetan (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian A (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian B (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tocharian C (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Tumshuqese (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| unidentified (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| unknown (script) | 0 | 0 |

| Uyghur (script) | 2 | 0 |

| Zhang-zhung (lang.) | 0 | 0 |

| Total* | 6,102 | 336 |

Bibliography

- Dabbs, Jack A., History of the Discovery and Exploration of Chinese Turkestan. The Hague: Mouton, 1963.

- Emmerick, Ronald E., Vorob’ëva-Desjatovskayja, Margarita I., Saka Documents VII: the St. Petersburg Collection. London: School of Oriental and African Studies on behalf of Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, 1993.

- Emmerick, Ronald E., Vorob’ëva-Desjatovsk, Saka Documents Text Volume III. London: School of Oriental and African Studies on behalf of Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, 1995.

- Hopkirk, Peter, Foreign Devils of the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. London: John Murray, 1980.

- Menshikov, L. N., Bianʹvėnʹ o vėimotsze. Bianʹvėnʹ “Desiatʹ blagikh znameniĭ.” Neizvestnye rukopisi bianʹvėnʹ iz Dunʹkhuanskogo fonda Instituta narodov Azii. Moscow: Izd-vo vostochnoĭ literatury, 1963.

- Menshikov, L. N., Bianʹvėnʹ o vozdaianii za milosti: rukopisʹ iz dunʹkhuanskogo fonda Instituta vostokovedeniia. Moscow: Izd-vo “Nauka,” Glav. red. vostochnoĭ lit-ry, 1972.

- Menshikov, L. N., Bianʹvėnʹ po lotosovoĭ sutre : faksimile rukopisi. Moscow: Izd-vo “Nauka,” Glav. red. vostochnoĭ lit-ry, 1984.

- Menshikov, L. N., Opisanie kitaĭskoĭ chasti kollektsii iz Khara-Khoto (fond P.K. Kozlova). Moscow: Izd-vo “Nauka,” Glav. red. vostochnoĭ lit-ry, 1984.

- Nikitin, A.B., ‘Sasanian coins in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow’. Ancient Civilisations from Scythia to Siberia 2/1 (1995): 71-91.

- Oldenburg, S.F., Russkaia Turkestanskaia Ekspeditsiia 1909-1910. Saint Petersburg: 1909-1910 Goda, 1914.

- Przhevalsky, N.M., Mongolia The Tangut Country And The Solitudes Of Northern Tibet Being A Narrative Of Three Years Travel In Eastern High Asia. London: , 1876.

- Przhevalsky, N.M., From Kulja: Across the Tian Shan to Lob-Nor. London: , 1879.

- Savitsky, Lev S., ‘Tunhuang Tibetan Manuscripts in the Collection of the Leningrad Institute of Oriental Studies’.

- Savitsky, Lev, Opisanie tibetiskikh svitkov iz dunkhuana v sobranii instituta vostokovedeniia a. Moscow: , 1991

- Tchuguevskogo, L. I., Kitaiskie Dokumenti iz Dun’khuna: Vipusk 1. Chinese Doucments from Dunhuang, Part 1. Moscow: , 1983.

- Vorobyoba-Desyatovskaya, M., ‘The Leningrad Collection of the Sakish Business Documents and the Problem of the Investigation of Central Asian Texts’. In Cadonna, Alfredo, Turfan and Dunhuang, the texts : encounter of civilizations on the Silk Route. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 1992.

- Xie Zhiliu, Dunhuang yishu xulu. Shanghai: Shanghai chubanshe, 1955.

- Xie Zhiliu, Dunhuang yishu xulu. Shanghai: Shanghai chubanshe, 1955.

If you have feedback or ideas about this post, contact us, sign in or register an account to leave a comment below