Collection items

All collection items

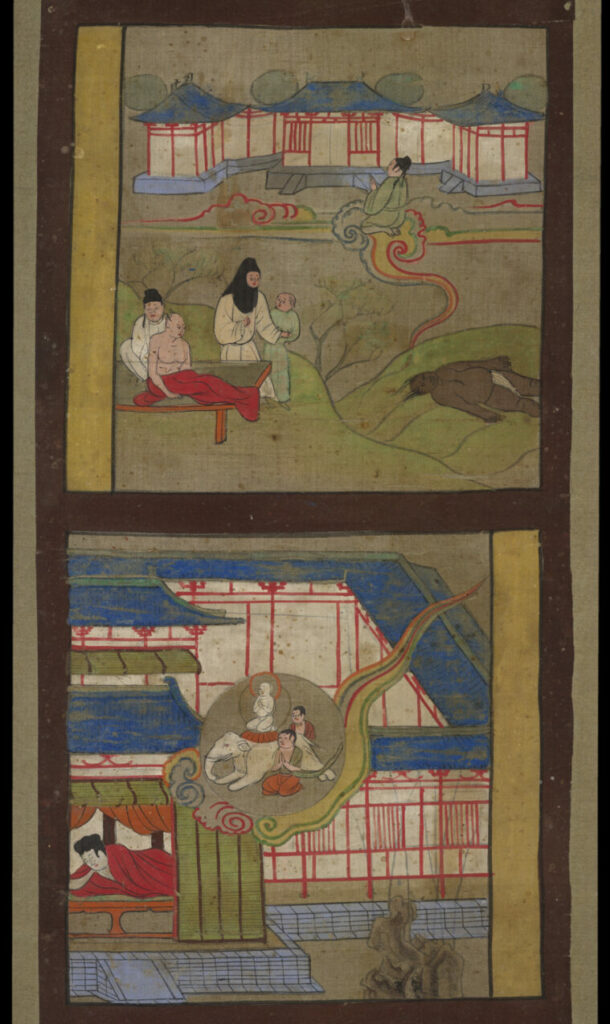

The Birth of Sakyamuni

This painted silk banner depicts four scenes from the final rebirth of the Buddha as Siddhartha Gautama or Sakyamuni. The banner was discovered in Mogao Cave 17, or the ‘Library cave’, in Dunhuang. The narrative scenes are arranged vertically, and begin from the top of the banner. Shown here are scenes two and three, and the full banner can be viewed in the IDP database.

The first scene is said to represent Dipankara’s prediction of the birth of Sakyamuni. In Buddhism, it is believed that there have been many Buddhas before Gauntama Buddha, and there will be more in the future. Dipankara is a Buddha of the distant past. According to Buddhist legend, Dipankara predicted that an ascetic named Sumedha would become the Gautama Buddha in a future lifetime. Here, Dipankara is shown touching the head of Sumedha.

In the second scene, the boy is now an old man and shown on his sickbed. To the left of this image is the body of the man in death. Above this, the man’s spirit, or the spirit of the Buddha, floats on a cloud.

Pictured in the third scene is a figure riding a white elephant, floating on a cloud toward a palace where Siddhartha Gautama’s mother Queen Maya sleeps. According to Buddhist legend, the conception of the Gautama Buddha occurred when Queen Maya dreamt of a white elephant descending from heaven and entering her side. The final scene depicts the queen’s confinement in pregnancy.

This item is featured in: The Origins of Buddhism.

Sketches of Mudras

This late-9th century illustrated scroll contains sketches of mudras. Mudras, meaning ‘seals’ or ‘signs’ in Sanskrit, are symbolic hand and finger gestures used in Buddhist art and in Buddhist practice. Particularly in Vajrayana Buddhism, mudras are used in rituals often in combination with mantras (chanting) and visualisation.

Each mudra is symbolic of a certain state of mind, Buddhist principle, or moment in the life of the Buddha. In Buddhist art, the Buddha and bodhisattvas are always depicted with their hands positioned in a mudra. These gestures can help the viewer to interpret and learn from the artwork. The mudras are drawn carefully, with occasional images of bodhisattvas in between. The scroll is most likely a reference text for monastic practitioners or artists, used as a guide for completing other paintings or performing rituals in the temple.

This item is featured in: Development of Buddhist beliefs.

Deer Jataka wall painting

This is a photograph of wall painting depicting The Deer of Nine Colours Jataka story. The mural sits on the west wall of Mogao Cave 257 in Dunhuang. Although this photograph is black and white, cave murals such as this are vibrant in colour.

The mural tells the story of a rare and beautiful deer with a multicoloured coat. One day, the deer rescued a man who had fallen into the river. Though he promised to protect the deer, the man, who was very poor, went to the palace and offered to lead the king’s hunters to the deer for a large reward. When the deer heard the hunters approaching and saw the man he had rescued, he called out in a human voice. He explained who he was, and that he had been betrayed. The king was angry and berated the man, but the deer explained that the temptation of riches was hard for some people to resist. Upon hearing this wisdom, the king agreed to pay the man his reward and granted the deer freedom to walk the forest without fear.

The continuous horizontal narrative style of this painting shows multiple scenes within one image. The full painting tells the story by moving from the left and right sides into the centre. This photograph shows the left side of the mural, and the edge of the central image in which the deer confronts the king’s hunters.

This item is featured in: Jataka Stories.

Wall painting from the Kizil Caves

This wall painting fragment depicts four standing Kushan worshipers with swords, thought to be the figures of donors who may have commissioned the creation of the cave. The painting comes from Kizil cave eight or ‘Cave of the sixteen sword-bearers’.

The Kizil Caves is a huge complex of rock-cut Buddhist caves, located in Xinjiang, China. The complex is one of ten built by the Buddhist kingdom known as Kucha, who ruled the area from the first to the 8th centuries CE. They are believed to be the earliest surviving Buddhist cave complex in China, with nearly 400 surviving caves.

These caves were used for various forms of Buddhist worship, and were filled with wall paintings and sculptures. Most of these are Buddhist artworks, but a number are also secular and reflect daily life in Kucha. The artworks are known for representing a fusion of artistic styles from various cultures along the Silk Roads. One of the most distinctive features of the paintings in the Kizil caves is the use of blue pigment, which can be seen in this artwork.

This item is featured in: Early Buddhist Kingdoms.

Talisman of the Polestar

This mid-10th century painting from Dunhuang depicts two celestial figures above an inscription. On the left is the spirit of the Pole Star, portrayed as a woman holding a brush and paper, signifying information. Next to her is Ketu, a figure of Vedic (ancient Indian) astrology.

Underneath the painting is talismanic formulae and a Chinese inscription in red, traditionally signifying good luck. The inscription reads: ‘Whoever wears in his girdle this talisman, which is a dharani talisman, will obtain magic power and will have his sins remitted during a thousand kalpas. And of the Ten Quarters all the Buddhas shall appear before his eyes. Abroad in the world he shall everywhere encounter good fortune and profit. Throughout his whole life he shall enjoy other men’s respect and esteem’. The donor dedicates the painting to Ketu and ‘the star that is genius of the northern quarter’.

The painting is an example of the coexistence and intermixing of Chinese astrological beliefs, Daoism and Buddhism after the latter had arrived in China. In the inscription, the painting is referred to as a talisman or dharani, an object that offers good luck or protective powers. Talismans were used by both Daoists and Buddhists alike.

This item is featured in: Chinese Buddhism on the Silk Roads.

Tibetan Tantra

This manuscript, discovered in the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang, is the Upayapasa-tantra or ‘Noose of Methods Tantra’. It is a Vajrayana scripture or ‘tantra’ with a commentary by the famous Vajrayana adept Padmasambhava, who is credited with a key role in bringing Buddhism to Tibet. In the image the commentary is visible in smaller writing in between the lines of the tantra, which are written in larger Tibetan letters.

Tantras are Buddhist scriptures focussed on ritual practices and techniques used in Vajrayana Buddhism. These techniques typically include the use of mudras (sacred hand gestures), mantras, and visualisation. This tantra is in a format known as a Pothi, a loose-leaf stack of horizontal papers usually held together with string.

This item is featured in: Tibetan Buddhism on the Silk Roads.

The itinerant storyteller

This paper painting was discovered in Mogao Cave 17 or the ‘Library cave’ at Dunhuang, and dates back to the late 9th century.

It depicts a traveller carrying a pack full of scrolls and a staff. A tiger accompanies him, and in the upper left corner is a small figure of the Buddha on a floating cloud. It is possible that the character could be a pilgrim monk. In later Chinese Buddhism, a similar figure, known as the Tiger Taming Monk, was one of the eighteen luohan, the original enlightened followers of the Buddha. Similar paintings have been identified as the famous Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang. He had a dream that convinced him to take a 17-year journey to India, the birthplace of Buddhism, preaching his faith and collecting sutras as he went. Alternatively, the image could depict a travelling storyteller, carrying illustrations for his public recitals. Characters such as this would have travelled the Silk Road telling popular Buddhist tales, illustrated by painted scrolls. Both storytellers and travelling pilgrim monks such as these would therefore have played a vital part in spreading Buddhist ideas and imagery upon their travels.

This item is featured in: Buddhist travellers and pilgrims.

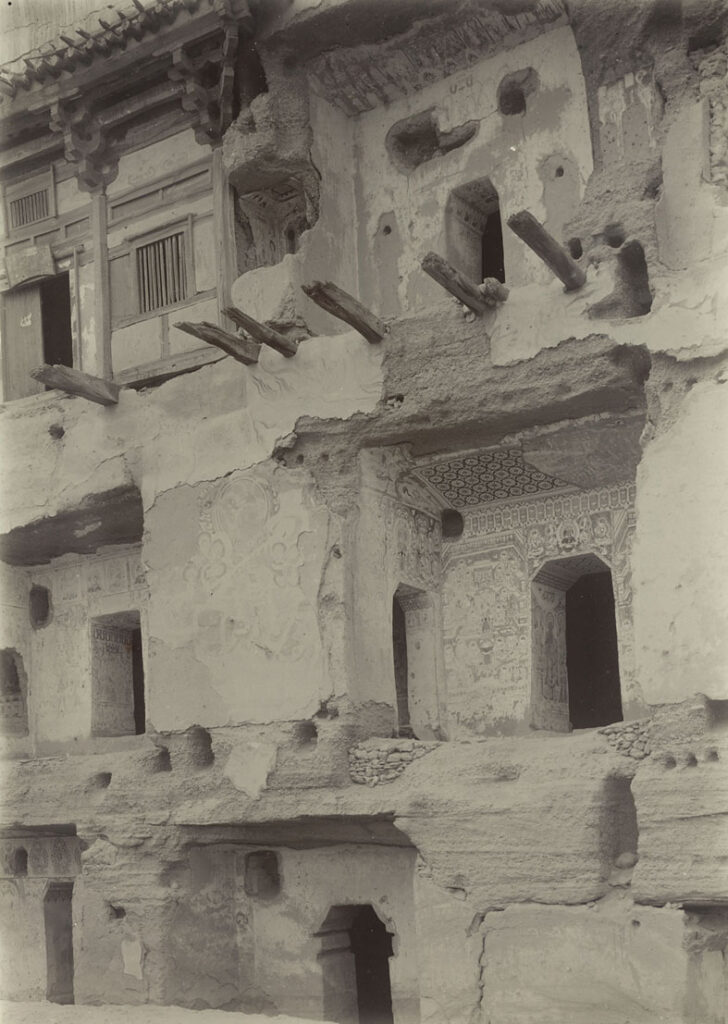

Photograph of the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang

This is a photograph of the Mogao Caves, a complex of nearly 500 monastic caves in Dunhuang, Gansu Province. Sir Marc Aurel Stein, a Hungarian-born British archaeologist, took the photograph in 1914 during his third expedition to the Mogao site.

The Mogao Caves, meaning ‘peerless caves’, were carved directly into cliff faces by Buddhist monks and were used as quiet spaces for worship and meditation. Hundreds of caves were excavated between the 4th and 14th centuries CE. Dunhuang, an oases city at the intersection of the ancient Silk Roads, became a pilgrimage spot and a hub of Buddhist practice. Today, the caves contain some of the best surviving examples of ancient Buddhist art, including wall murals, portable paintings, sculptures carved directly into the walls, textiles and various devotional objects. One cave, known as Cave 17, was filled with manuscripts and sealed around 1000 CE. Its rediscovery in 1900 revealed an unrivalled source for knowledge of official and religious life in Dunhuang.

This item is featured in: Buddhist caves: Dunhuang.

Colophon from the Diamond Sutra

This is a colophon from a Chinese copy of the Diamond Sutra, the world’s earliest dated, printed book. This Buddhist scripture is one of the most influential sutras in Mahayana Buddhism.

A colophon is a brief note in a manuscript that contains information about the work’s publication, authorship, or printing. The colophon at the end of this copy of the Diamond Sutra tells us a lot about when and why it was created. It reads ‘Reverently made for universal distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the fifteenth day of the fourth month of the ninth year of the Xiantong reign’. In the western calendar, this date translates to the 11 May 868. In Buddhism, spreading the word of the Buddha is an important way of earning karmic merit. It is believed that the printing and copying of Buddhist texts is one way of doing this. By sponsoring the printing of this scroll in their names, Wang Jie would have acquired merit for both his parents and himself.

This item is featured in: Buddhist texts: The Diamond Sutra.

Painting of Avalokitesvara with donors

The construction and decoration of Buddhist caves, such as the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang, were often commissioned by Buddhist patrons. Along with the devotional Buddhist artworks stashed in these caves, it was also common practice to paint the image of donors as well. Doing so could generate karmic merit for the donors and their families.

The lower half of this 983 CE silk painting depicts the donor Mi Gongde, known as ‘Prefect of Dunhuang’. In the top row he is shown with his three sons, his wife and three of his daughters; on the bottom row are his four grandsons, another daughter, his granddaughters and grand-daughter-in-law. On the top half is ever-popular bodhisattva Avalokitesvara.

This item is featured in:

Buddhist art and practice.

Thousand-armed, thousand-eyed Avalokitesvara

This is a mid-10th century painting on paper depicting Avalokitesvara. It was discovered in Mogao Cave 17, or the ‘library cave’, at Dunhuang. Avalokitesvara is a bodhisattva, a cosmic Buddhist deity. He is the embodiment of compassion and typically is portrayed helping those in trouble.

This painting shows a simplified version of a common manifestation of Avalokitesvara, the thousand-armed, thousand-eyed form. This depiction represents Avalokitesvara’s ability to hear and reach out to all suffering beings. However, this image only shows ten arms in any detail, four of which hold the sun, the moon, a skull-headed mace and a trident. The artist has indicated the rest of the arms in the halo. Although the iconography is clear, the execution suggests a poorer donor who could neither afford silk nor a professional artist.

This item is featured in: Bodhisattvas.

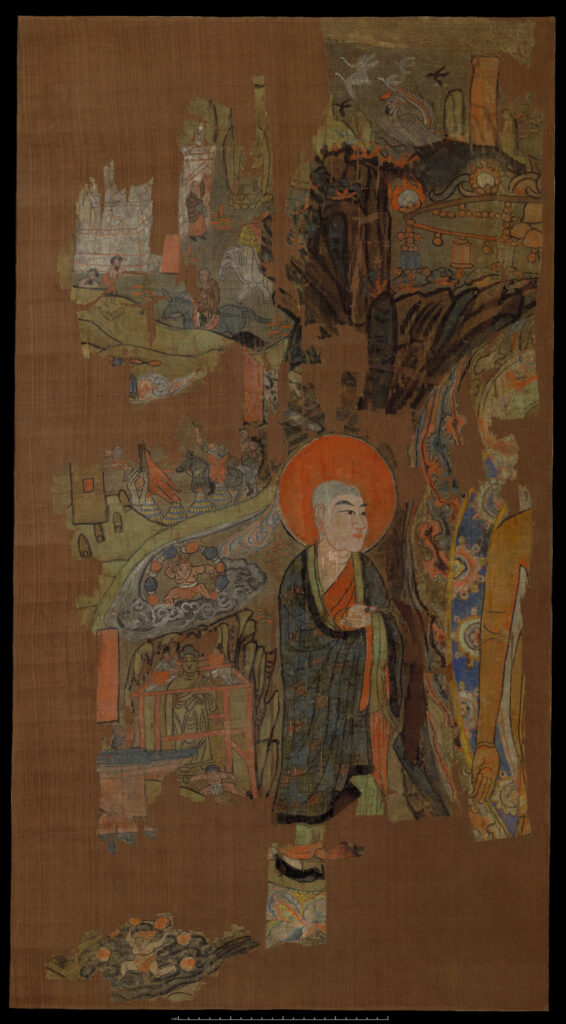

Ksitigarbha

This 9th century silk painting depicts the bodhisattva Ksitigarbha. It was discovered in Cave 17, or the ‘library cave’ at Dunhuang.

In Buddhism, bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who stay in the world of suffering in order to help others reach enlightenment. There also exist celestial bodhisattvas, deities such as Ksitigarbha, who embody the traits of enlightenment.

Ksitigarbha (or Dizang in China) is known as the guardian of beings in the ‘Hell Realm’ (Naraka), one of the six realms one can be born into through karma and rebirth. He is known for his vow never to enter nirvana until this realm has been emptied of all beings. He is also seen as a guardian of the deceased, especially children, between death and the next life. In Buddhist art, he is often represented as a monk, which is said to represent his vow. This representation can be seen in this painting, where Ksitigarbha can be seen with a shaven head, wearing a patchwork robe or kasaya.

This item is featured in: Bodhisattvas.

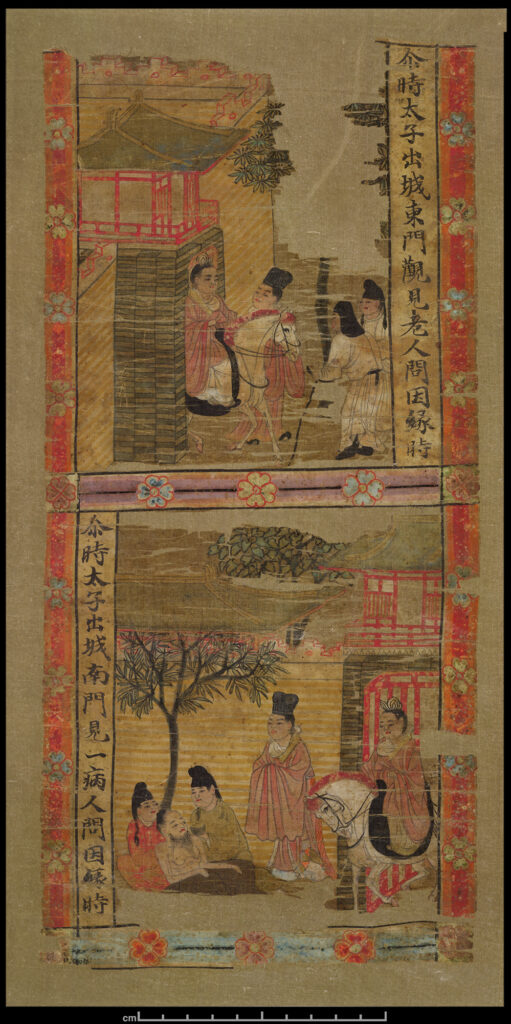

Siddhartha’s encounters with human suffering

This 8th or 9th-century painted silk banner shows two scenes from the life of the Buddha. It was discovered in Mogao Cave 17 at Dunhuang. The two scenes, stacked one of top of the other, depict two of the four encounters made by Siddhartha Gautama when he left the palace.

According to Buddhist legend, the historical Buddha was born a prince known as Siddhartha Gautama. He lived a sheltered life of luxury in his father’s palace. Aged 29, Siddhartha became curious about life outside the palace walls, and became aware of human suffering for the first time. He had four encounters in the outside world that would change his life. He saw an old man, a sick man, a corpse, and a serene holy man. From these experiences, he learnt that life is full of suffering, is impermanent and eventually comes to an end. The banner depicts the prince on his white horse encountering old age and sickness, two of the four encounters that caused him to leave the palace for good.

This item is featured in: The Origins of Buddhism.

Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish

This manuscript is a copy of a popular Buddhist scripture called the Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish. It was discovered at the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang and dates back to late 5th to early 6th century.

The Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish is a popular collection of Jataka stories. Jataka stories are moral tales that recount the former incarnations of the Buddha, either in human or animal form. These stories appear in Buddhist art and literature, and were often used as teaching aids. The stories in the Sutra of the Wise and Foolish explore the concept of karma. Each story demonstrates how suffering in one’s current lifetime can be traced back to events in past lives. The knowledge of this cycle offers the possibility of transcending it.

The origin of this sutra is uncertain. A common belief however is that Chinese monks transcribed and translated these stories from lectures given by Khotanese monks in Central Asia. The sutra was later translated into Tibetan and then into Mongolian, where it came to be known as the Ocean of Narratives (Uliger-un dalai). This particular copy is written in Chinese.

This item is featured in: Jataka Stories.

Sakyamuni preaching on Vulture Peak

This fragment of an 8th to 9th century silk painting depicts Sakyamuni, the historical Buddha, preaching to disciples at Vulture Peak.

On the right edge of the fragment is the downward pointing arm of the Buddha, rendered in gold and surrounded by an elaborate mandala. This image of the Buddha would have been the centre of the image, attended by monks on either side, one of which is prominent in this fragment. Behind the Buddha are dark rocks, and a vulture perching on the mountain peak, signifying Vulture Peak.

Vulture Peak is a mountain in the historical town of Rajagaha (now Rajgir) in Nalanda, India. It is known to be the Buddha’s favourite retreat, where he would deliver his sermons to the Sangha.

This item is featured in: Transmission of Indian Buddhism.

Votive panel from Dandan-Uiliq

This painted wooden votive panel from the 6th century CE was found in Dandan-Uiliq, a ruin north-east of Khotan. It depicts religious deities from both Buddhism and Hinduism, illustrating the cultural interactions that took place on the Silk Roads.

On one side are two seated Buddhas and two seated bodhisattvas. Painted on the reverse are three seated figures. The two flanking deities are believed to be Hindu deities incorporated into the Buddhist pantheon. The left deity holding a Vajra has been identified as Indra, god of the atmosphere. The three-headed god on the right is believed to be either Brahma or the Sogdian god Weshparkar. It has been suggested that the central four-armed figure that holds the sun and the moon is a goddess of Abundance.

This item is featured in: Early Buddhist Kingdoms.

Water and moon Avalokitesvara

This accomplished mid-10th century painting on silk shows Avalokitesvara in a popular Chinese form, the so-called Water and Moon Guanyin.

Avalokitesvara, known in Chinese Buddhism as Guanyin, is a bodhisattva who embodies compassion. The ‘water moon’ manifestation usually depicts Guanyin in a relaxed pose, encircled by a full moon, contemplating its reflection in water. It is believed that this represents the deity in his ‘pure land’ or paradise.

Note the elaborate canopy above him, below which can be seen the king and two attendants on a small cloud. At the bottom of the painting is an altar, next to which is a figure identified as the painting’s donor. The iconography is clearly Chinese, indicated by the bamboo, which is not found around Dunhuang

This item is featured in: Chinese Buddhism on the Silk Roads.

Uyghur illustrated manuscript

This illustrated manuscript is a fragment from a copy of the Dasakarmapathavadanamala, or ‘The Garland of legends pertaining to the ten courses of action’. The text is in Old Turkic language, written vertically in the Uyghur script, and was likely translated from a version in the ancient Indo-European language Tocharian A. It is one of the most important surviving Buddhist narrative works in the Uyghur language.

‘The Garland of Legends’ is a collection of Buddhist stories focusing on the workings of karma, each chapter dealing with one of the ten Kammapatha, or ‘paths of action’. The illustration, which depicts several people in prayer, one figure in flames, and two people entwined with a large serpent, bears the influence of the Uyghur Manichean art style. During the Uyghur Empire of the 8th century CE, the Uyghurs adopted Manichaeism as the state religion. After the fall of the empire, those that migrated and established the Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho shortly converted to Buddhism.

This item is featured in: Late Buddhism on the Silk Roads.

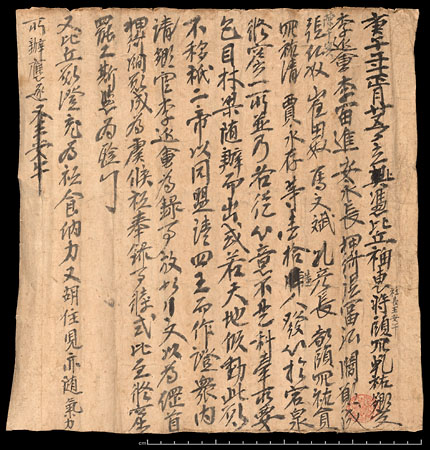

Letters of introduction for a Chinese pilgrim

This manuscript contains letters of introduction for a pilgrim monk from China. The letters are addressed to monastic leaders and officials in the next town, requesting that they help the monk on his journey.

Once Buddhism had become embedded in China, many Chinese monks embarked on a pilgrimage to India, the birthplace of Buddhism. They usually did this with the aim of visiting sacred sites, and collecting new scriptures to translate. They would travel the overland routes of the Silk Roads, which could be a long and treacherous journey.

Because these letters are written in Tibetan, the monk’s journey probably took place during the Tibetan occupation of Eastern Central Asia in the mid-8th to mid-9th century. It could also have taken place in the decades following when Tibetan was still a ‘lingua franca’ (a common language between groups who speak different languages). The monk is described as a great ascetic, scholar, and upholder of virtue. He is planning to visit the great monastic university of Nalanda in North India and the pilgrimage sites connected with the birth, life and death of the historical Buddha Sakyamuni.

This item is featured in: Buddhist travellers and pilgrims.

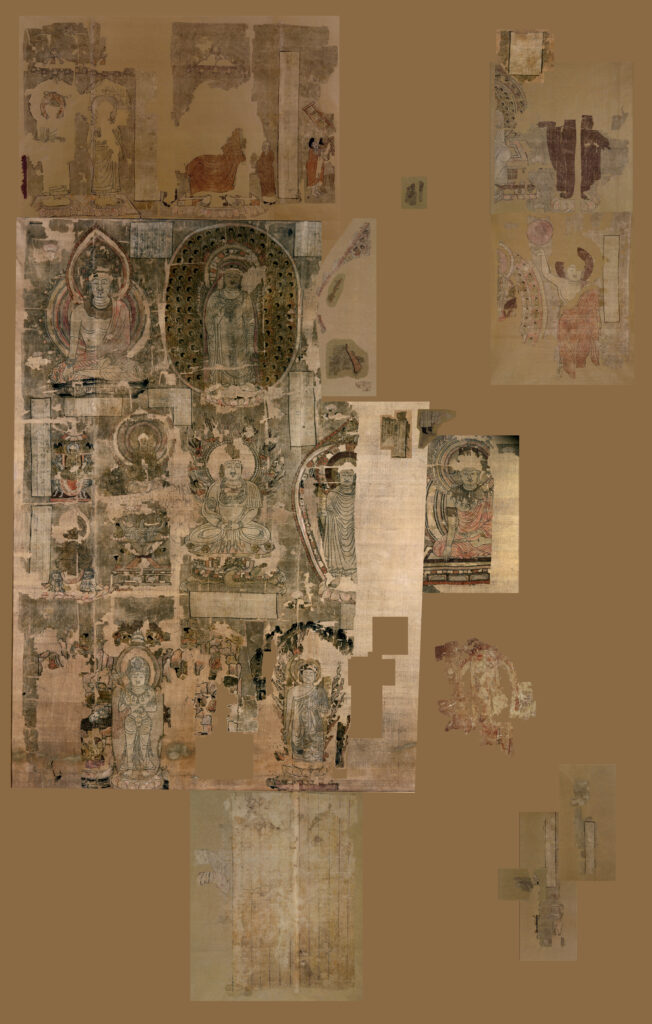

Virtual reconstruction of the Famous Images of the Buddha

After the Mogao caves came to international attention in the early 1990s, explorers and archaeologists of various nationalities acquired many of the items found there. These were dispersed across the globe and are now held in various collections. This painting, Famous Images of the Buddha, was found in Cave 17 in an extremely fragmentary state. Parts of it are now found in both the British Museum and the National Museum, New Delhi.

Here, these separated fragments have been brought together in a virtual reconstruction of the full-size painting. It features various depictions of the Buddha and bodhisattvas, and it relays some Buddhist stories. The virtual reconstruction is the work of Professor Roderick Whitfield after many years of research into both collections.

This item is featured in: Buddhist caves: Dunhuang.

Photograph of Dunhuang Mogao Cave 217

This is a photograph of Mogao Cave 217, one of the ancient Buddhist grottoes at Dunhuang. The west-portion of the south wall shown here is covered in elaborate paintings. Although the photograph is in black and white, these murals are vibrant in colour, rendered in earthy red and bold blue pigment.

Painted on the ceiling is a grid of Buddha paintings known as the ‘Thousand Buddha’ motif. On the walls are devotional images of deities and narrative paintings. One of these narrative paintings, identified by imagery of travellers, horses and mountains, depicts a parable from the Lotus Sutra, the ‘Illusory City’. In this parable, a caravan leader guides a group of travellers on a long journey through the desert toward some treasure. The travellers soon become tired and discouraged. To ensure the group continue their journey, the leader conjures an imaginary city where they can rest. He then reveals that the city was an illusion, and that the real destination is close. In the story, the leader is the Buddha, the illusory city represents enlightenment, and the treasure represents Buddhahood, the highest goal in Mahayana Buddhism.

This item is featured in:

Buddhist art and practice.

Mandala of the Buddha Vairocana

This ornate red ink drawing on paper is a Mandala. It features the Buddha Vairocana surrounded by other deities, lotus flowers and the symbol of the Vajra. Vairocana (‘the illuminator’ in Sanskrit) is known in some traditions to be the primordial or cosmic form of the historical Buddha. In Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, he is considered the first of a group of five transcendent celestial Buddhas who represent different aspects of enlightenment and have existed from the beginning of time.

Mandalas are symbolic representations of the universe in its ideal form. They are used in Vajrayana practice as a visual aid for meditation, and as a tool for visualising the spiritual journey to enlightenment. They can also represent the ‘palace’ of the deity that resides in its centre, and in practice, one may use the mandala to invoke and embody this deity. They can be created in a number of mediums, but are typically intricate symmetrical designs loaded with Buddhist symbolism.

This item is featured in:

Buddhist art and practice.

Manjusri on lion with two attendants

This woodblock-printed prayer sheet depicts Manjusri, the bodhisattva who embodies wisdom. The print was discovered in Mogao Cave 17, or the ‘Library cave’, at Dunhuang.

In Buddhism, bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who stay in the world of suffering in order to help others reach enlightenment. There also exist celestial bodhisattvas, deities such as Manjusri, who embody the traits of enlightenment.

Here, Manjusri (or Wenshu in China) is pictured on a lion, holding a sword, flanked by two attendants. Underneath the illustration is a short prayer and a dharani, a statement that has protective powers when recited or chanted.

This item is featured in: Bodhisattvas.

Letter on 11-year-old becoming a nun

Buddhist Monasteries are governed by a set of rules outlined in a scripture called the Vinaya, the code of conduct for monks and nuns. One of these rules deems that the minimum age for novices joining a monastery was age 12. This rule however was not strictly enforced.

This is a letter dated 938 CE from Cao Yijin, the ruler of Dunhuang. It concerns the request of a local couple for their daughter, Shenglian, aged 11, to become a novice. The Governor has granted permission, made his mark at the end and added three red seals. A minimum age for novices was also enshrined in secular law, hence the need for Shenglian’s parents to seek permission from the ruler of Dunhuang.

This item is featured in: Buddhist religious life.

Mahapratisara dharani

This elaborate Chinese woodblock print depicts the bodhisattva Mahapratisara surrounded by a dharani in Sanskrit. A dharani is an amulet, an incantation that when written or read aloud is said to offer powers of protection. These would be recited during Buddhist meditative practice.

Mahapratisara is believed to be the personification of a dharani as a deity, and takes the form of an eight-armed protective bodhisattva. She is also known as ‘the great amulet’ or ‘great queen of spells’, and first emerged around the 8th century. Her protective powers can be invoked through the recitation of the dharani.

This item is featured in: Buddhist religious life.

Illustrated Lotus Sutra

The Lotus Sutra (Saddharma Pundarika Sutra in Sanskrit) is one of the most influential texts in Mahayana Buddhism. It was created sometime between the 1st century BCE and 2nd century CE, and was first translated into Chinese in the 3rd century CE. The main message of the Lotus Sutra is that all living beings can attain Buddhahood and reach nirvana. This message opens up the Buddhist path to all, and had not been established in any sutra before.

This illustrated booklet is a copy of Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra, or the Avalokitesvarasutra. It focusses on the bodhisattva (Buddhist deity) known as Avalokitesvara, who embodies the quality of compassion. He is usually portrayed helping human beings in their time of need, and this sutra depicts him rescuing people from various dangers, such as drowning or fires. In China, this bodhisattva is known as Guanyin, and takes a female form.

By the 9th and 10th-century Chapter 25 was commonly copied as a separate text, often in small booklets such as this one. Each page of this copy is illustrated and coloured with vibrant red pigment. It is one of thousands of copies of the Lotus Sutra found in the Mogao caves at Dunhuang, China.

This item is featured in: Development of Buddhist beliefs and Chinese Buddhism on the Silk Roads.

Sibi Jataka

This is a photograph of a wall painting depicting the Jataka story known as the Sibi Jataka or the Tale of King Sibi. The painting covers the north wall of Mogao Cave 254 in Dunhuang, and dates back to 439-534 CE.

Jataka stories are moral tales that recount the former incarnations of the Buddha, either in human or animal form. These stories appear in Buddhist art and literature, and many are depicted in murals in the Mogao caves at Dunhuang. The Sibi Jataka tells the story of King Sibi, a previous incarnation of the Buddha. The story has several variations, but all of them tell the story of a selfless king who gives part of himself to save another being. The version depicted here relates to the story in which King Sibi comes across a dove being pursued by a falcon. The dove seeks refuge in the king, but the falcon demands he surrender it as its prey. Eventually the falcon agrees to leave the dove alone on the condition that the king offers his own flesh, equal in weight to the dove. As depicted in the painting, he willingly cuts off his own flesh to protect the dove.

This item is featured in: Jataka Stories.

Gandharan birch-bark scroll

This is a fragment of a Gandhari birch bark scroll. The collection of 29 bark scroll fragments date back from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE, making them some of the oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts.

Gandhara (now parts of present day Pakistan and Afghanistan) was a major centre for Buddhism and the creation of Buddhist art and literature. It also played an important part in the transmission of Buddhism across Central Asia into China and Tibet.

These manuscripts were stored and preserved for thousands of years in clay jars. The text is written in the ancient Gandhari language in Kharosthi script, scribed in black ink on pieces of birch bark strips glued together. The fragments come from a number of separate scrolls, which were the work of various scribes. They contain a variety of Buddhist sutras, poems, commentaries, hymns and Buddhist scholarly texts. These include Gandhari copies of the Rhinoceros Sutra, an early text on the benefit of solitary practice, and the Dharmapada, a collection of Buddhist teachings in verse form. They also include Avadanas, which are stories that demonstrate the workings of karma.

This item is featured in: The Kushan Empire

The Book of Zambasta

This is a leaf from the Khotanese text The Book of Zambasta, probably the most important local Buddhist composition from Khotan. Parts of it date from the 5th to 6th centuries but judging from references to the Tibetans, it likely was not completed until the 7th century. The text’s original title is unknown. It was given the title The Book of Zambasta by scholars because it was copied at the request of an official named Zambasta. The text is a ‘metrical’ or poetic account of various different aspects of Buddhism. As well as its significance in the history of Khotanese Buddhism, The Book of Zambasta was also an important source in deciphering the Old Khotanese language.

While based on Indian sources, it is an original Khotanese text. Numerous fragments exist of at least five different copies, proving its popularity extended into the 10th century, well after the date of composition.

This item is featured in: Early Buddhist Kingdoms.

Tibetan Bodhisattva

This 10th-century silk painting of a bodhisattva is said to show either Tibetan or Khotanese stylistic influences. It was found in Mogao Cave 17 in Dunhuang and dates back to the early 9th century, the period of Tibet’s influence in Central Asia.

Recent scholarship has suggested that the figure depicted may be the bodhisattva Akasagarbha. This bodhisattva, whose name signifies the sky or space, has the ability to purify bad karma. He is pictured with emblems of the sun and moon, and a canopy.

At the bottom is an inscription in Tibetan, which reads ‘The Holy Lord of the Directions [who is accompanied by] all the Hum mantras of the space above’. On the right side is the name: ‘Te Goza Legmo.’ The feminine termination ‘mo’ suggests that the artist, or perhaps the sponsor, was a noblewoman.

This item is featured in: Tibetan Buddhism on the Silk Roads.

Fragment of Tangut Mahaprajnaparamita sutra

This is a fragment from a Tangut copy of the Mahaprajnaparamita sutra, dating from 1000 – 1400 CE. It was discovered in Kharakhoto, an abandoned city built by an ancient civilisation known as the Tangut Empire. The empire, also known as Western Xia, flourished from the 11th to 13th centuries CE. The Tangut Empire was dedicated to Mahayana Buddhism, and during its reign translated an abundance of sutras into the Tangut language.

The Mahaprajnaparamita sutra or ‘The Large Sutra on the Perfection of Wisdom’ is a collection of Prajna Paramita sutras. These sutras are concerned with the idea of ‘transcendental wisdom’, knowledge of the ‘illusory’ nature of all reality. They are some of the most important scriptures in Mahayana Buddhism. This Tangut copy of the text was likely copied for the accumulation of religious merit of spreading the Buddha’s word.

This item is featured in: Late Buddhism on the Silk Roads.

Pledge for the upkeep of the Mogao Caves

The caves at Dunhuang were busy working shrines. The visitors, the smoke and deposits from the incense and lamp oil, and the effects of the scouring sand all took its toll on the paintings and sculptures. Donors were not only required for the building and decorating of the caves, but also for their upkeep.

This document is a pledge made by sixteen men, dated 25 March 970, to make themselves responsible for ‘the upkeep of the cave temples in the valley of the Dang River’, that is, the Dunhuang caves. The pledge ends: ‘Even if Heaven and Earth collapse, this vow shall remain unshaken.’

This item is featured in: Buddhist caves: Dunhuang.

The Diamond Sutra frontispiece

This Chinese copy of the Diamond Sutra, complete with an ornate illustrated ‘frontispiece’, is the world’s earliest dated, printed book. It was one of the most significant ancient Buddhist manuscripts discovered in Mogao Cave 17, or ‘the Library Cave’ at Dunhuang.

The Diamond Sutra was first translated from Sanskrit into Chinese around 400 CE. As noted in the colophon (a note at the end of the scroll), the production of this copy was sponsored by Wang Jie and completed 11 May 868. The text was woodblock printed onto seven sheets of yellow-dyed paper and joined together to form a 5-metre horizontal long scroll.

The Diamond Sutra is one of the most important sutras in Mahayana Buddhism. In Sanskrit, it is known as Vajracchedika Sutra, which roughly translates to ‘The Diamond that Cuts through Illusion’. This refers to the Buddhist concept of Prajna – the wisdom that, like an indestructible diamond, cuts through ignorance and reveals the nature of reality. The text itself takes the form of a conversation between the Buddha and his disciple Subhuti, who discuss the Buddhist belief that the material world is an illusion.

This item is featured in: Buddhist texts: The Diamond Sutra.

Sketches from the Sutra of Maitreya

Drawn on this 9th-to-10th century scroll are preliminary sketches for a large wall painting in Mogao Cave 196, one of the rock-cut Buddhist grottoes in Dunhuang. The ink drawings depict the arrival of Maitreya. In Buddhism, it is believed that there have been many Buddhas before Gautama Buddha, and there will be more in the future. Maitreya is considered the Buddha of the distant future, and it is thought that his arrival will a time of great abundance.

In these sketches the artist concentrates on groups of figures that are central to the painting’s meaning, celebrating an easy, fruitful existence after Maitreya’s arrival. The scenes depict agricultural work resulting in a productive harvest. A man urges his two work oxen to plough a plot with a wooden switch. A woman wields a sickle to cut the wheat, whilst other workers can be seen threshing and tossing the grain and sorting the harvest into bushels. At the end of the scroll, people feast in a tent.

This item is featured in:

Buddhist art and practice.

Stencil for ‘Thousand Buddha’ motif

This pounce or stencil was one of nine from the Dunhuang cache of manuscripts. These designs, with holes punctured at intervals along thick, black lines, were used to produce the repetitive Thousand Buddha designs on cave ceilings painted in the 9th and 10th centuries. The upper sections of cave-shrines were difficult to reach and the design demanded the execution of identical figures. In order to produce these images, one would place the pounce against the wall and apply powder over its surface. When removed, a skeleton of dots remained on the wall. Artists would then paint over these.

Examples of the ‘Thousand Buddha’ motif can be found in many of the Mogao caves in Dunhuang. Repetition of the Buddha’s image was believed to be one way of spreading his word and generating karmic merit. It also relates to a core Mahayana teaching, that every sentient being has the potential to achieve Buddhahood.

This item is featured in:

Buddhist art and practice.

Samantabhadra

This is a section from a silk painting depicting the bodhisattvas Samantabhadra, Manjusri, and various forms of Avalokitesvara. This section, taken from the bottom left of the painting, depicts Samantabhadra. It dates back to 864 CE and was discovered in Cave 17, or the ‘Library cave’, at Dunhuang.

In Buddhism, bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who stay in the world of suffering in order to help others reach enlightenment. There also exist celestial bodhisattvas, deities such as Samantabhadra, who embody the traits of enlightenment.

Samantabhadra (Or Puxian in China) is associated with Buddhist meditation and practice and is considered the protector of those who teach the dharma. His name means ‘universal worthy’ or ‘all good’. Here, he is shown sitting on a white elephant surrounded by a halo and flanked by attendants. In the full painting, Samantabhadra is pictured opposite the bodhisattva Manjusri, mirroring each other’s pose.

This item is featured in: Bodhisattvas.

Buddha with begging bowl

This 9th-century painting, embellished with red pigment, depicts the Buddha seated on a lotus holding an alms-bowl. It was discovered in Cave 17 of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang.

Buddhist art often depicts the Buddha with an alms or begging bowl. The importance of this object traces back to a mixture of legend and history. During the Buddha’s time travelling North India with the Sangha giving teachings, they would collect alms, relying on the lay community to feed them. This is also how monasteries traditionally operated after the Buddha’s death. The lay community donated food, money, clothes, and shelter, and in return, they could receive teachings from the monastery, and generate karmic merit.

A number of Buddhist legends reference the begging bowl, and one of these refers to the Buddha’s time meditating under the Bodhi tree before reaching enlightenment. It is said that he was offered a bowl of rice, and realised that he needed to eat enough to sustain him on the path to enlightenment. After becoming enlightened, he discarded the rest of the rice. The bowl therefore symbolises the ‘middle path’ between indulgence and deprivation.

This item is featured in: Buddhist religious life.

Ritual implement

This object was discovered in Cave 17 of the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang. Its purpose is unknown, but it is believed to have been used by Vajrayana Buddhists performing tantric rituals.

On the octagonal base is a drawing of the tantric deity Vajrasattva, who is associated with purification. Purification is an important part of initiation for students of Vajrayana Buddhism. The object therefore may have been used in an ‘empowerment’ ritual, one of the requirements needed before a student is allowed to begin performing Vajrayana practice.

Vajrayana practice includes a number of ritual techniques, such as the repetition of mantras, the use of mudras, visualisation, and yoga. Performance of these rituals also includes the use of talismans and ritual objects. It is possible that this implement is a Tibetan tsakli, which may have been placed on a shrine. Tsakli are miniature paintings, sometimes mounted on sticks, which depict deities and offer protection.

This item is featured in: Buddhist religious life.

Altar diagram for recitation ritual

This 10th-century diagram illustrates how to prepare an altar for the recitation of the Usnisa Vijaya Dharani. A dharani is an incantation used in Buddhist rituals that offers powers of protection. The Usnisa Vijaya Dharani is said to help purify one of their bad karma, extend their life, and prevent them from rebirth into one of the lower realms. The diagram was discovered in Mogao Cave 17 in Dunhuang, and indicates how these caves may have been used for Buddhist practice.

In the diagram, an image of the Buddha is placed at the centre, surrounded by lamps, vases and circular bowls for incense and water. As noted in the bottom of the diagram, the officiating Tantrist would be seated at the south side of the altar with an incense burner behind him. There are also images of Bhaiṣajyaraja and Bhaisajyasamudgata (bodhisattvas of healing), together with the bodhisattvas Avalokitesvara and Mahasthamaprapta.

This item is featured in: Buddhist religious life.