IDP Collections in other institutions

Some countries have less of a history of archaeological expeditions to the sites of the Eastern Silk Road, but still contain collections of great value for research. This summary of historical and holdings information was produced by the IDP team, led by Susan Whitfield, in December 2005. The information was last updated in September 2011. While we are keeping this text up as a background resource, please be aware that new information may have come to light since its initial writing.

Collections in Sweden

History of the Swedish Collections

Collections in Finland

History of the Finnish Collections

Collections in Denmark

History of the Danish Collections

Collections in Ireland

Collections in India

Collections in the USA

Collections in Sweden:

History of the Swedish Collections

Sven Hedin made four expeditions to Central Asia between 1893 and 1935 (see IDP News 21). His first lasted four years, from 1893–97, and was devoted to mapping and exploring unknown areas of northern Tibet. Hedin also acquired archaeological material from a few sites. On his second expedition (1899–1902) Hedin mapped the Tarim river and the Tibetan high plateau and, in the process, he discovered traces of old settlements, including what was later identified as Loulan. He took away with him a collection of wooden and paper documents and other objects. His third expedition (1905–08) did involve any archaeological work, but focused rather on political reportage. Finally, between 1927 and 1935, Hedin undertook a series of expeditions, with different sponsors, participants and purposes. One of his collaborators was Folke Bergman, who put together substantial archaeological collections which were taken back to Sweden but were returned to China in the 1950s, in accordance with an agreement Hedin had negotiated with the Chinese authorities. This material is now in the History Museum in Beijing.

The first Swedish missionary station in Eastern Turkestan was set up in Kashgar in 1892 by Rev. N.F. Höijer. In addition to their ordinary religious duties, the missionaries devoted much time to humanitarian work as well as to scholarly and cultural activities, such as publishing and printing, a comprehensive report of which is presented in Gunnar Jarring, Prints from Kashgar (1991). Their work was discontinued in 1938. The diplomat and Turkologist Gunnar Jarring (1907–2002) spent some time in Kashghar in 1929–30 as a Ph.D. student and brought a great number of manuscripts back to Lund University Library (see the digitised catalogue from Lund University). Jarring’s own fieldwork on Eastern Turki (Uighur) dialects was published between 1946 and 1951 under the collective title of Materials for the Knowledge of Eastern Turki.

Several other collections can be found at various places in Sweden, such as the National Archives, the Mission Covenant Church of Sweden and Lund University Library.

Collections in Sweden: Contents and Access

Sven Hedin (1865–1952) was responsible for sending Central Asian material to Sweden. His collections are housed in various museums, mostly in Stockholm, where the National Museum of Ethnography has most of the manuscripts and artifacts, as well as Hedin’s library, maps, photographs, films, drawings and personal belongings. The Museum of Natural History owns the botanical, zoological, geological and other related collections; and Hedin’s personal archives are deposited with the National Archives. The Hedin Foundation is developing a website.

Further information, including maps of Hedin’s expeditions, can be found at the website of the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

Gunnar Jarring’s private collection of Central Asia publications belongs to the Swedish Royal Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities. The collection consists of ca 5000 volumes, a number of manuscripts, catalogues and maps as well as more than 3000 offprints. All of the most renowned accounts of expeditions to Central Asia and adjoining regions from the late 19th and early 20th centuries can be found in this collection, along with lesser known accounts as well as most of the abovementioned Kashgar prints. Gunnar Jarring’s last contribution to his own collection of Central Asia publications was a handwritten manuscript for a second enlarged edition of his An Eastern Turki–English Dialect Dictionary from 1964. This manuscript, which is a valuable source of cultural historical knowledge about Eastern Turkestan, is being edited for publication in the near future.

Read More: The Turkological Legacy of the Swedish Diplomat Gunnar Jarring

Paper presented at the International Conference on Central Eurasian Studies: Past, Present, Future, University of Maltepe, Istanbul, 17–19 March 2009.

Author: Birgit N. Schlyter

DOWNLOAD (PDF 184KB)

Collections in Sweden: Bibliography

- Hedin, Sven Anders, Bealby, J. T.Through Asia. En färd genom Asien 1893-1897. London: Methuen and Co., 1898.

- Hedin, Sven Anders, Bealby, J. T.Central Asia and Tibet Towards the Holy city of Lassa. Asien: Tusen mil på okända vägar. London: Hurst and Blackett, 1903.

- Hedin, Sven Anders, Lyon, F. H.Scientific Results of a Journey in Central Asia and Tibet 1899-1902. Sidenvägen. En bilfärd genom Centralasien. Stockholm: , 1904-7.

- Hedin, Sven Anders, Huebsch, A.My Life as an Explorer. London: Cassell and Company, 1926.

- Hedin, Sven Anders, Cant, H. J.Across the Gobi Desert. Auf grosser Fahrt: meine Expedition mit Schweden, Deutschen und Chinesen durch die Wüste Gobi 1927-1928. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1931.

- Hedin, Sven Anders, Lyon, F. H.The Silk Road. Sidenvägen. En bilfärd genom Centralasien. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1938.

- Jarring, Gunnar, Materials to the Knowledge of Eastern Turki: Tales, Poetry, Proverbs, Riddles, Ethnological and Historical Texts from the Southern Parts of Eastern Turkestan with Translation and Notes, Parts I-IV. Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup, 1946-51.

- Jarring, Gunnar, An Eastern Turki–English Dialect Dictionary. Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup, 1964.

- Jarring, Gunnar, Eva ClausonReturn to Kashgar: Central Asian Memoirs in the Present. Durham: Duke University Press, 1986.

- Jarring, Gunnar, Prints from Kashgar: The Printing-office of the Swedish Mission in Eastern Turkestan. History and Production with an Attempt at a Bibliography. Stockholm: Swedish Research Institute of Istanbul, 1991.

- Jarring, Gunnar, Central Asian Turkic Place-Names – Lop Nor and Tarim Area – An Attempt at Classification and Explanation Based on Sven Hedin’s Diaries and Published Works. Stockholm: The Sven Hedin Foundation, 1997.

- Schlyter, Birgit (ed.), Bibliography of Literature on Journeys and Explorers in Asia in the Gunnar Jarring Library at Stockholm University. Stockholm: Department of Central Asian Studies, 2007.

Collections in Finland:

History of the Finnish Collections

Copyright: The Finno-Ugrian Society, Helsinki

The National Museum of Finland (VKK 269:416) ©

The presence of a Silk Road collection in Finland results from the 1906–08 Russian-sponsored expedition to northern China led by Finnish citizen Baron Carl Gustav Emil Mannerheim, later Marshal Mannerheim, president of Finland (1944–46) and defender of Finnish independence from Soviet Russia. (Finland had been an autonomous protectorate of Russia until 1918.)

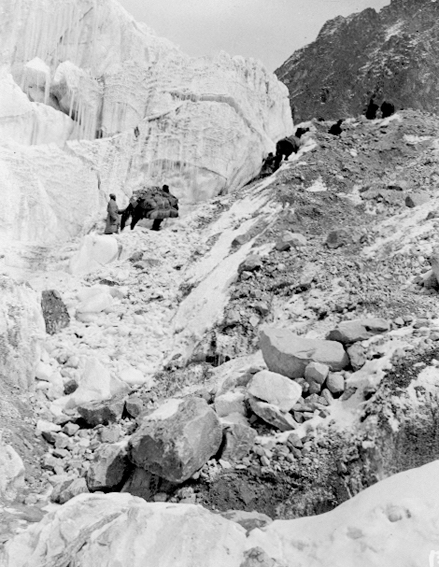

At the turn of the twentieth century, Mannerheim was a career soldier in Tsarist Russia’s imperial army. He was promoted to the rank of colonel while fighting in the Russo-Japanese war (1904–5), following which he was then sent on a reconnaissance expedition (1906–08) to northern China, sponsored by the Russian military. Between 1906 and 1908, Mannerheim’s expedition travelled from Samarkand to Peking with detours on the way to map previously unknown areas. The terrain was harsh in the extreme, with steep mountains and deep gorges, often covered by ice and snow, and its completion represented a tremendous feat of endurance and horsemanship. The expedition’s aim was to increase Russia’s intelligence on China, in the context of growing interest in the region by Japan and other foreign powers. Mannerheim’s brief focussed essentially on gathering political and military information. He carried out extensive mapping and reported on the extent of Japanese influence, local attitudes to Russia, Japan and China, particularly in the border areas, the development of schools, roads and other infrastructure, weather conditions, defence capacity, population density and government structures.

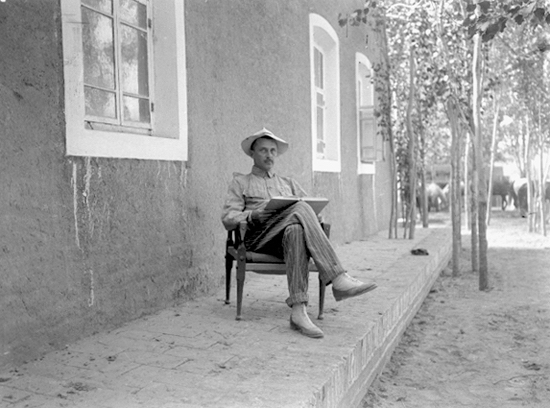

In the weeks before departure, Mannerheim spent time in Helsinki, preparing for his travel and research. He read travel and scholarly books, including those by Aurel Stein (see British collections); and he made contact with Paul Pelliot (see French collections). Aware of current excavations in the region, he realised the opportunity to add a further dimension to his expedition which would not only add to the interest but might also provide cover for more sensitive aspects of his agenda. Through Otto Donner (1835–1909), Sanskrit scholar and Finnish Minister of Education, he met members of the Finno-Ugrian Society. They briefed Mannerheim on the linguistic and ethnographic heritage of the region and asked him to make detailed ethnographic studies. They also asked him to collect or copy historic manuscripts and inscriptions likely to be of linguistic or cultural interest. Mannerheim also met the trustees of Finland’s National Museum, the Antell trustees, who were keen to acquire historical manuscripts and artefacts relating to the languages and cultures of the region. They financed his collecting activities on behalf of the National Museum.

Copyright: The Finno-Ugrian Society, Helsinki

The National Museum of Finland (VKK 269:131) ©

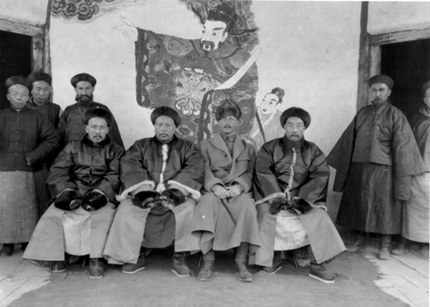

The expedition, including a cook and two cossacks, left Samarkand by train for Andijan on 28 July 1906, heading on via Osh to Kashgar, which they reached on 17 August, after three weeks hard travelling in the same caravan as Paul Pelliot (see French collections).Thereafter, the two expeditions travelled separately. Mannerheim spent a month in Kashgar, checking out reports of Japanese presence in the area. Being obliged to await a travel permit from Peking, he managed to obtain a local travel permit which allowed him to explore to the south-east, as far as Khotan, making archaeological and ethnographic observations and returning to Kashgar in early January 1907. During this period, Mannerheim was fully occupied in mapping and recording meteorological and ethnographic data, but he also managed to collect hundreds of ancient manuscript fragments from Turfan and Khotan which were purchased locally, including the Sanskrit and Khotanese Buddhist texts published by J.N. Reuter (Reuter, 1913), and four Uighur loan contracts first published by G.J. Ramstedt (Ramstedt, 1940). It was while based in Kashgar that Mannerheim began to return material to Finland.

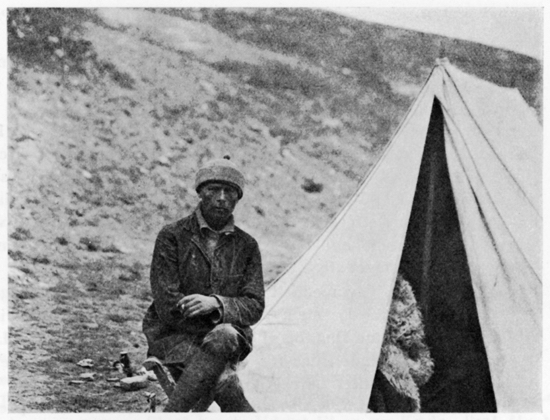

At the end of January 1907, Mannerheim set out again across difficult terrain, towards Urumqi, reaching Aksu on 2 March and leaving at the end of the month, having mapped 200 miles of the Tauschkan-Darja (Toxkan river). On 12 April he reached Kuldja, where he collected his travel permit. He continued to Karashahr (5 July), excavating and purchasing along the way and returning further finds to Finland. On 24 July, he arrived in Urumqi and one month later, towards the end of August, he continued to Turfan, where he acquired several manuscripts. Thereafter he visited Barkul in mid-October, and Hami where he met Aurel Stein, before crossing the Gobi to Anxi. At this point, Mannerheim was only forty miles from Dunhuang and his decision to visit the oasis but not the caves at Mogao has intrigued scholars. Perhaps he was more interested in recreational game-hunting than looking for manuscripts, as some have inferred from Mannerheim’s own comments in his diaries. Possibly he was slow to grasp the significance of the discoveries at Dunhuang. More likely, having remarked in his diaries on the destruction wrought by amateur excavations in the Turfan region, he may well have felt disinclined to compete with the expertise and single-mindedness of Stein and Pelliot. Above all, having already spent considerable time and available finances on archaeological and ethnographic acquisitions, he would have felt obliged by this point to turn his attention to intelligence-gathering and press on to the next stages of his expedition. Budget was also a limiting factor: Mannerheim wrote to his Finnish sponsors from Anxi, asking for further funds in order to be able to continue his collecting activities. Arguably, had funds arrived in time, he might have spent longer in the area.

Exhibition: Mannerheim in Central Asia 1906-1908 in the Museum of Cultures

As it was, Mannerheim turned his back on Dunhuang and continued to Suzhou (1 December) and Ganzhou (Christmas 1907), where he researched Uighur language and culture on which he later published an article in the Journal de la Societé finno-ougrienne. On 29 January 1908, the expedition reached Lanzhou from where Mannerheim visited the Labrang monastery and acquired a range of Tibetan cultural artefacts. He then continued to Xian, Luoyang, Kaifeng and Taiyuan, from where he travelled five days and 120 miles north, to the monastery complex of Wutaishan, to visit the Dalai Lama on 26 June 1908. He then travelled along the Mongolian border before returning to Beijing where he spent a month at the Russian embassy, writing his report, organising his material, redrawing maps and arranging his notes. He returned to Russia via Japan.

By the autumn of 1908 Mannerheim was back in Finland, handing over his collection. He never again participated in a similar expedition, although he maintained a lifelong interest in the collections. He is chiefly remembered for his subsequent military and political career, when he played a key role in establishing Finland’s independence from Russia (1917) and subsequent non-aligned status in a continent convulsed by communism, fascism and two world wars.

Mannerheim’s expedition diary was published in 1940, in English, Finnish and Swedish editions, as Volume 1 of Across Asia from West to East. It contains some of his expedition photographs taken between 1906 and 1908, alongside descriptions of the life and customs, flora and fauna, trading practices, landscapes and people encountered in the villages and towns along the route. Volume II, also published in 1940, contains further photographs plus descriptions, by scholars, of Mannerheim’s archaeological and manuscript findings from east Turkestan; ethnographic data; contemporary tribal clothing and artefacts; extensive meteorological notes; and redrawn maps from the expedition. The locations and circumstances in which the manuscripts and artefacts were obtained by Mannerheim are not always recorded.

Collections in Finland: Content and Access

Lacking both the time and experience of his contemporaries, Mannerheim excavated only briefly and occasionally, using local staff recruited for the purpose: most of his collection was purchased from locals. This, and his brief from Helsinki, resulted in a wide-ranging collection which contains:

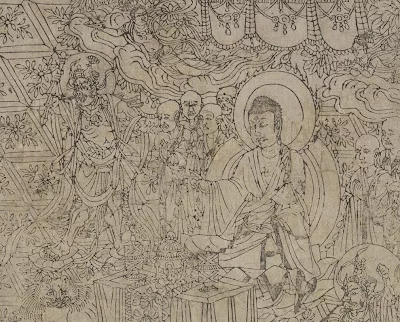

- several thousand mainly Buddhist manuscripts and fragments from the Khotan and Turfan areas, in Chinese, Uighur, Tibetan, Khotanese, Sogdian; plus one Mongolian and one Middle Persian (Manichean) text

- 1,500 expedition photographs including many of local villages, towns and people

- ancient ceramics and gems

- 250 ancient coins, mostly from Khotan

- hundreds of contemporary artefacts including jewellery, costumes

- hundreds of religious objects, including Buddhist temple tapestries

- ethnographic data

- meteorological data

- cartography

- an expedition diary

Ownership is divided between the Finno-Ugrian Society and the National Board of Antiquities and the material is deposited in several locations in Helsinki. Everything has been catalogued and much has been digitised.

1.1 National Board of Antiquities

Mannerheim’s photographs, including the original negatives, are now held in the Archives for Prints and Photographs of the National Board of Antiquities. The National Board of Antiquities can provide copies of digitised images and copyright information.

1.2 Access to the National Board of Antiquities:

Nervanderinkatu 13

Helsinki

Finland

Consult the NBA website for contact details.

2.1 Helsinki University Library

The Finno-Ugrian Society has deposited Mannerheim’s manuscripts in the Orientalica Collection at Helsinki University Library, along with Mannerheim’s collection of oriental books, in Mongolian, Turkic and Tibetan languages and dating from the 18th century.

2.2 Access to Helsinki University Library:

Unioninkatu 36 (PB 15)

00014 University of Helsinki

Finland

Open Mondays to Saturdays; closed Saturdays in July and all Sundays

Consult the Helsinki University website for further information.

3.1 The Museum of Cultures, Helsinki

The Museum of Cultures, which opened in 1999, now holds the bulk of the Mannerheim collection (not all on permanent display), previously housed in the National Museum. The collection includes over 1,000 objects and all the diaries and notes from the 1906–08 expedition. There is a regular programme of temporary exhibitions, sometimes incorporating the Mannerheim material. C.G. Mannerheim in Central Asia gives a detailed description of the collection; and Photographs by C.G. Mannerheim from his Journey across Asia, 1906–08 shows photographs with a commentary in Finnish and English.

3.2 Access to the Museum of Cultures:

Tennispalatsi Floor 2

Eteläinen Rautatiekatu 8

Helsinki

Open Tuesdays-Sundays; closed Mondays.

Consult the Museum of Cultures website for further details.

3.3 The Mannerheim Museum, Kaivopuisto, Helsinki

Mannerheim lived in the seaside house where the museum is housed from 1924 until his death in 1951 and filled it with furniture, decorative arts and crafts acquired during his travels. It was purchased in 1957 by the Mannerheim Foundation and became a commemorative museum, housing a collection of Mannerheim’s ethnographic collections and memorabilia. Everything is displayed as it would have been when the house was lived in; and the original interior and furniture are also preserved. Exhibits include hunting trophies, military medals, books, and some artefacts from the 1906–08 expedition such as contemporary tribal clothing, cooking utensils, spinning and weaving equipment, Tibetan Buddhist thangkas, temple tapestries and other religious objects. A Gentleman’s Home: The Museum of Gustaf Mannerheim contains a descriptive account of the museum and contents.

3.4 Access to the Mannerheim Museum:

Kalliolinnantie 14,

Helsinki

Opening hours are limited.

Consult the Mannerheim Museum website.

Bibliography

- Koskikallio, Petteri, Lehmuskallio, Asko, Halen, Harry, C.G. Mannerheim in Central Asia. Helsinki: National Board of Antiquities, 1999.

- Mannerheim, Gustaf Emil, Hilden, Kaarlo (ed.), Birse, Edward. Across Asia from West to East in 1906-1908. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian Society, 1940.

- Mannerheim, Gustaf Emil, Sandberg, Peter (ed.), Photographs by C.G. Mannerheim from his Journey across Asia 1906-1908. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian Society, 1990.

- Ramstedt, G. J., Four Uigurian Documents. Helsinki: , 1940.

- Reuter, J. N., Some Buddhist Fragments from Chinese Turkestan in Sanskrit and Khotanese. London: Luzac and Co., 1913-18.

Collections in Denmark:

History of the Danish Collections

Arthur Bollerup Sørensen © Royal Library (Det Kongelige Bibliotek)

In the autumn of 1915 the chief telegraphist in Shanghai at the Great Northern Telegraph Company, Mr. Arthur Bollerup Sørensen (1880–1932) travelled through Dunhuang on his way home to Copenhagen. Originally, he had planned to visit Lhasa in Tibet but it was not possible for him to obtain the required travel permits due to political and military problems. He then changed his plans and decided to travel through Turkestan following the old Silk Road to Semipalatinsk in Russia (now Kazakhstan) and from there on to Copenhagen where he arrived in October 1915.

Mr. Arthur Bollerup Sørensen financed three expeditions. The first took place in 1909 and took him from Beijing to the Gobi Desert; the second, in 1915, from Shanghai to Xining in Qinghai province; and the third, in 1921–22, from Shanghai to Nagachuk in Tibet. While travelling, he recorded topographic, astronomical and meteorological data that are now kept in The Royal Danish Geographical Society.

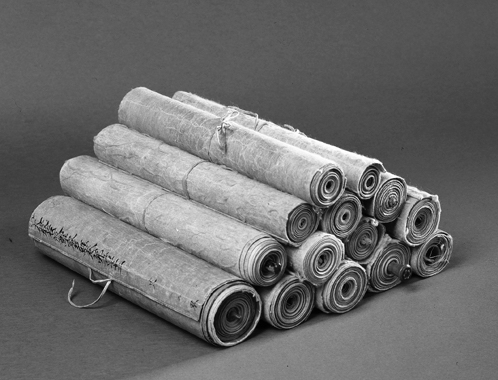

When he was in Dunhuang in 1915 he was approached by a monk, probably Wang Yuanlu (c. 1849–1931), who wanted to sell him old manuscripts claiming that some of them dated back to the Tang period (618–907). Mr. Bollerup Sørensen purchased fourteen scrolls containing sixteen texts and donated them all to The Royal Library on the 29th November 1915.

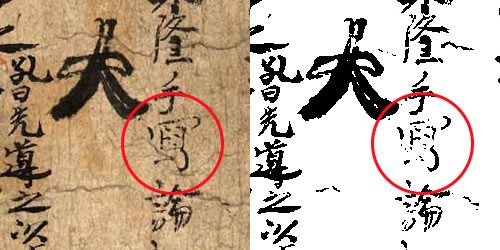

It was only in 1954 that a hand-list was published by Walter Fuchs (1902–79) titled Udførlig beskrivelse af KB’s 14 Tun-huang ruller (Detailed description of the Royal Library’s 14 Dunhuang scrolls). A complete description was published in 1988 by Jens O. Petersen titled ‘The Dunhuang Manuscripts in the Royal Library of Copenhagen’ in Analecta Hafniensia, 25 Years of East Asian Studies in Copenhagen (ed. Leif Littrup, Copenhagen: Curzon Press, 1988, pp. 112-117). An un-authorized translation into Chinese of an earlier version of Jens O. Petersen’s description was published in 1987: 课本哈根皇家图书馆藏敦煌写本 /(丹麦)彼得森撰 / 荣新江 译 in:敦煌学辑刊 1987/1 (总第十一期) pp. 132-137.

Collections in Denmark: Content and Access

Photographic Studio, The Royal Library © Royal Library (Det Kongelige Bibliotek)

The scrolls consist of fifteen Buddhist texts and one Daoist text. The texts are either whole chapters or parts of various canonical texts. One of the texts consists of chapter fifteen of Huayanjing lun and seems to survive only in this collection. Another text – juan 1 of the translation of Yogacaryābhūmi-śāstra by Facheng – contains a date corresponding to A.D. 855.

Access: Contact the Oriental Collection at The Royal Library, Copenhagen:

Mailing address:

Oriental and Judaica Collections

The Royal Library

P.O. Box 2149

DK-1016 Copenhagen K

Visitors:

Centre for Orientalia & Judaica

The Black Diamond (Søren Kierkegaards Plads 1)

Level E-West (entrance: Centre for Manuscripts & Rare Books, level F-West)

Mon-Tue, Thu-Fri 10-17; Wed 12-19

Phone: Oriental Collection +45 33 47 48 90 or +45 33 47 48 87

E-mail: [email protected]

See for instructions: http://www.kb.dk/en/nb/samling/os/orienthaandskrifter.html

Bibliography

- Fuchs, Walter, ‘Udførlig beskrivelse af KB’s 14 Tun-huang ruller’ (A hand-list published by Walter Fuchs (1902-1979): “Detailed description of the Royal Library’s 14 Dunhuang scrolls.”).

- Petersen, Jens O., ‘The Dunhuang manuscripts in the Royal Library of Copenhagen’. In Analecta Hafniensia, 25 years of East Asian Studies in Copenhagen. Leif Littrup (ed.), Copenhagen: Curzon Press, 1988.

- Rischel, Anna-Grethe, ‘Preliminary analysis of the Danish Collection of Dunhuang manuscripts’. Manuscripta Orientalia, International Journal for Oriental Manuscript Research 8.3 (2002): 53-58.

Collections in Ireland

The Chester Beatty Library in Dublin holds four Dunhuang manuscripts in Chinese and one in Tibetan. These were purchased in 1955 and the Chinese ones are now available on the IDP database.

Collections in India

The Silk Road Exhibition Cat No. 223, page 269.

The Victoria and Albert Museum © V&A

Material from Aurel Stein’s first and second expeditions (see British collections) was sent initially to London and, from there, some was transferred to India as the Government of India was co-sponsor of his expeditions. Material from the first expedition (1900-01) was sent to the Indian Museum, Calcutta and the Art Museum, Lahore. Material from the second expedition was sent originally to the Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi (ASI), then under the British Government. who had provided funding to Stein. The findings were kept temporarily in Srinigar. Material from the third expedition was sent directly to India. In 1918 the murals were transferred to Delhi and Stein paid regular visits to supervise the construction of a building to display this material. In 1958 the material was handed over to the National Museum, New Delhi. This comprises over 11,000 items, including hundreds of silk, hemp and paper banners from Dunhuang; over 2000 pieces of stucco; 900 fragments of wall paintings; and over 600 textile pieces.

The textiles were transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Collections in the USA

There are various collections of Central Asian manuscript and other material in various US libraries, museum, universities and private collections. The largest Dunhuang manuscript collection is at Princeton University, comprising about 80 documents. The James and Lucy Lo archive of photographs is also held here. The smaller collections of material in the Freer Gallery in Washington DC (one manuscript and two Dunhuang paintings), the University of California at Los Angeles (one manuscript), and the University of California at Berkeley (two manuscripts), are now available online on the IDP database. It is planned to make other collections similarly available.

The Yale collection is small and includes sculpture fragments and manuscripts on paper and wood. It was bequeathed by Ellsworth Huntington (1876–1947), a well-known geographer and Yale academic who had traveled widely in central Asia between 1903 and 1906, primarily to carry out research into climate change and its effects on Asian civilizations.

If you have feedback or ideas about this post, contact us, sign in or register an account to leave a comment below